US Federal R&D spending decline: a breakdown

In the US, federal R&D expenditures are down since their peak in 1964 at 1.86% of GDP. Now they are 0.61% of GDP. This from ITIF is representative of this narrative:

Or here's Gruber and Johnson,

“From 1940 to 1964, federal funding for research and development increased twentyfold. At its peak in the mid-1960s, this spending amount was around 2 percent of annual gross domestic product—roughly one in every fifty dollars in the United States was devoted to government funding of research and development (equivalent, relative to GDP, to almost $400 billion today). The impact on our economy, on Americans, and on the world was simply transformational.” [...]

“Federal spending on research and development peaked at nearly 2 percent of economic output in 1964 and over the next fifty years fell to only around 0.7 percent of the economy.16 Converted to the same fraction of GDP today, that decline represents roughly $240 billion per year that we no longer spend on creating the next generation of good jobs. Should we care? If there is socially beneficial research and product development to be done, surely the innovative companies of today will take this on?”

There are two reasons why this chart and overall story is not as bad as it seems.

R&D spending is one of the drivers of technological progress which in turn generally (But not necessarily!) leads to economic growth. So less R&D spending, regardless of where it is coming from is bad news. The second reason would be that perhaps the kind of R&D that governments fund is different from that of the private sector. The strongest argument for government funding of R&D is in basic science; the one for which one can make the public goods argument. The closer to application R&D is, the more benefits can be captured by their performer and less of a strong case for funding it.

The reason for why the chart may be misleading is that such a decline has not been mostly in the kind of research a public funding body would be better at -basic research-. The decline has been driven by the development component and particularly it has been driven by a conspicuously large peak in spending around in 1964.

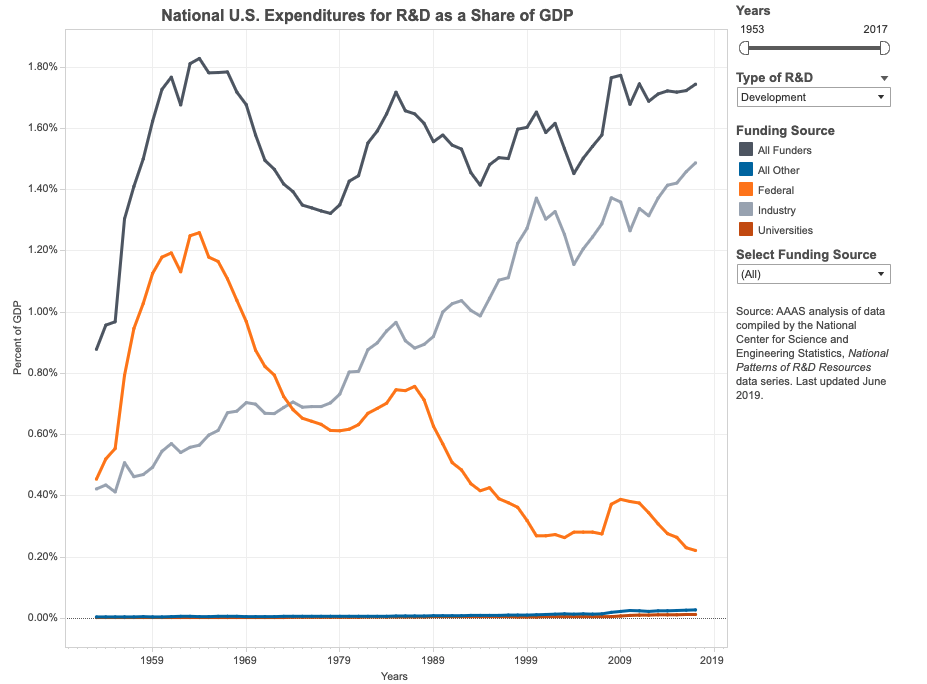

Here's the full view for the D component of R&D (These and other figures are taken from here):

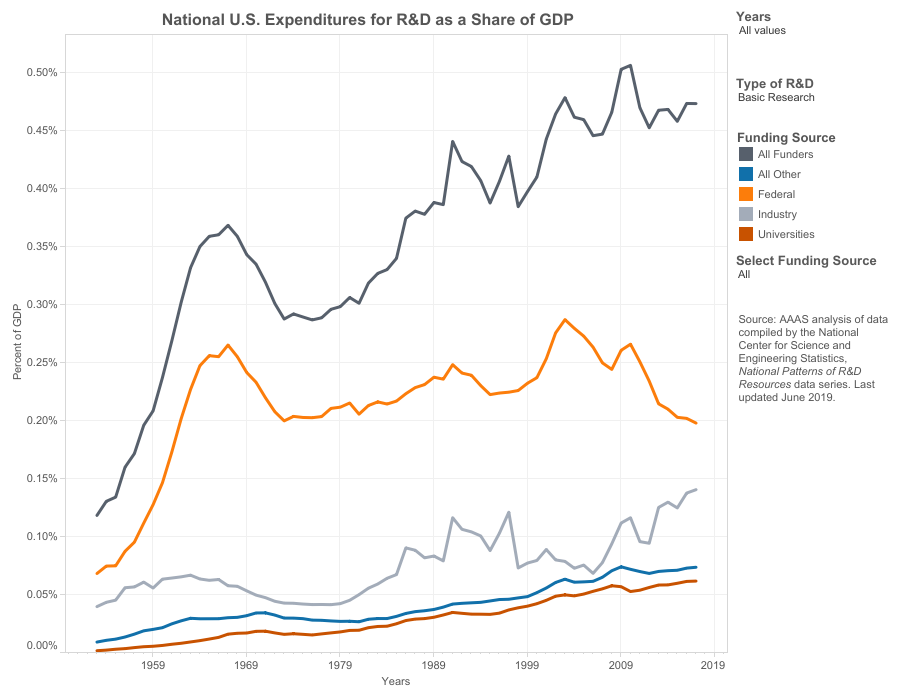

And lastly, basic research at a federal level did initially decline, but then gradually recovered up until 2004, having declined since.

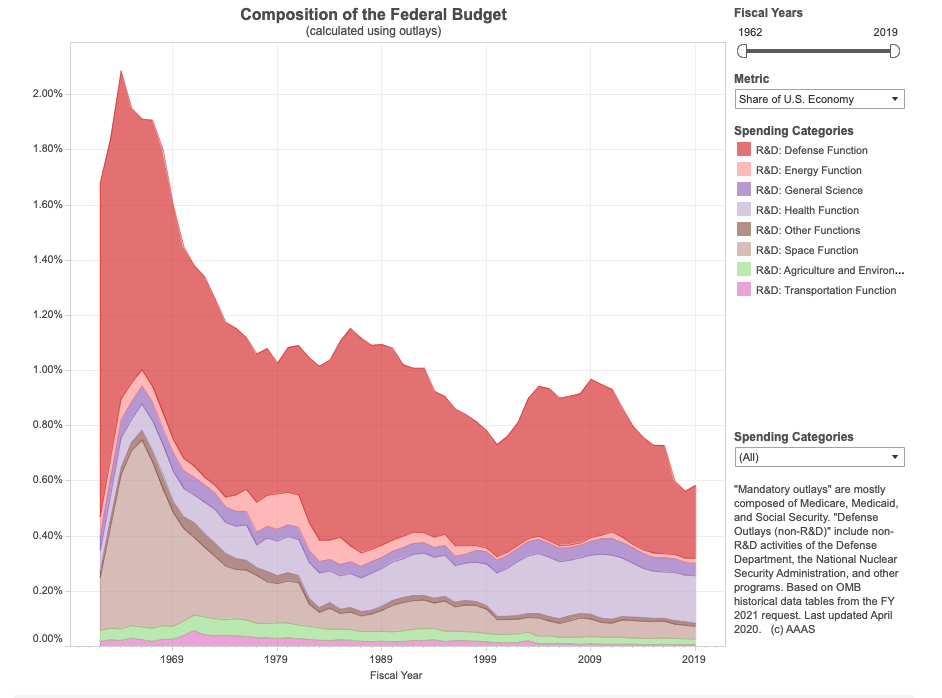

So why was that? Well, looking at the composition of federal R&D expenditure over time it's not hard to see why:

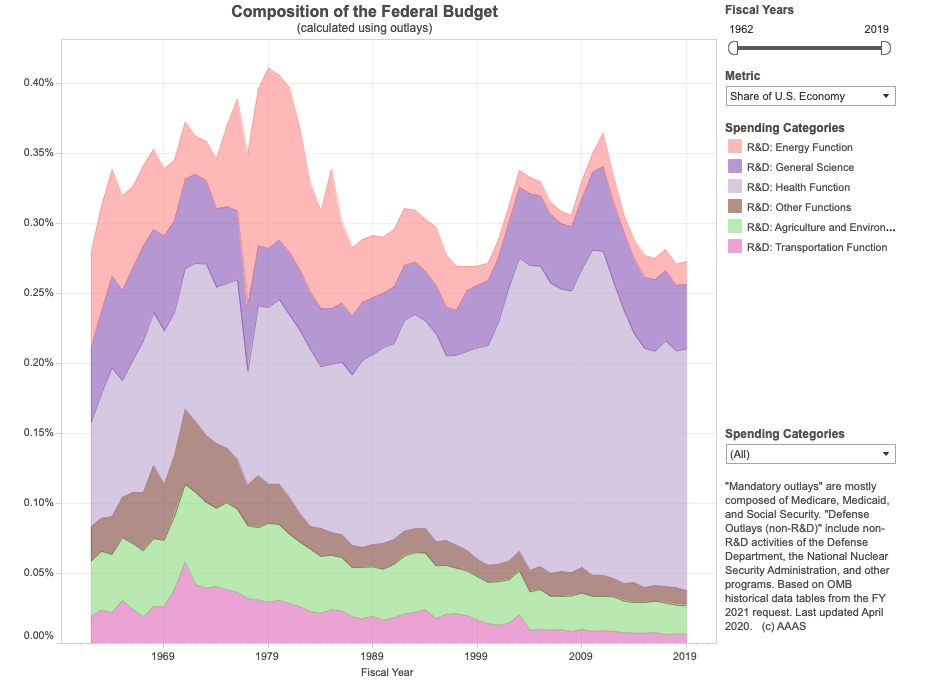

If it's not completely clear, this is what this looks like without Space and Defense:

Here there is no dramatic decline. There is a decline, but rather than the almost fourfold drop in the headline figure, the drop here would be, peak to bottom, less than 2x. This may be even less dramatic if we consider that a lot of that energy R&D may have been for nuclear weapons development.

My reason for excluding Space (That is, NASA) and the DoD is that the former (that peak in the chart is the Space Race) was a one of a kind endeavor that was heavily skewed towards the development of highly specific systems (rockets and spacecraft). The same is true in general of the kind of expenditure done by the US DoD, it is heavily skewed towards highly applied use cases, and these are less likely to generate the kind of spillovers one wants R&D for, relative to other kinds of R&D in more basic or non-defense areas (My general view is that defense R&D is very likely not as good as its civilian counterpart for progress in non-military technology and productivity in general). You can see here that very little of what the DoD funds is Research, and in particular DARPA is a tiny entity within the overall DoD budget.

The AAAS dataset doesn't go before the peak so we can't say if the DoD was doing more basic science back then, but their contribution within the broad funding ecosystem seems small in that regards,

I think a better story here is that the composition of federal R&D funding has changed, areas other than health have stagnated or shrunk as a fraction of GDP. This is in turn not necessarily a bad thing if you believe that biology is the most Endless Frontier there is, relative to other areas.

Now, what should one do with this knowledge? The first thing is that this knowledge defeats one heuristic for allocating R&D as a percentage of GDP: "If it is lower than historical trends, raise it until it reaches the historical average (Or maximum)". If one takes the Cold War and the Space Race as abnormal events that had their own non-economic drivers then it's unclear what a good historical figure to climb up to would be.

But one could still say "The economy was capable of sustaining over 2% of federal R&D back then, so that should still be doable; in fact that money could be deployed towards a Space Race but for Aging or for Material Sciences". That is a better and more valid argument.

To be sure, there are other reasons why the decline is troubling: One could make the argument that GDP growth aside, the US needs a strong military and the DoD R&D budget shrinking is not good news. This is something I have not considered here.

One could further say, why 2% and not more? Or in general, the very interesting question of what's the optimal share of GDP that should go to R&D? As much as politically feasible? On most models, formal or not, of R&D funding it seems that that is indeed the right conclusion if one wants to increase GDP growth, so the question then becomes what are the best places to scrape more R&D funding from (reallocating budget, taxes?). And there is a parallel question on how to spend that money. My intuition is that this matters on the margin more than just increasing the budget. Not all R&D is created equal, both in field and mode of spending.

Citation

In academic work, please cite this essay as:

Ricón, José Luis, “US Federal R&D spending decline: a breakdown”, Nintil (2021-02-22), available at https://nintil.com/us-science-without-space/.

Comments