Talent: a review

Talent (Tyler Cowen & Daniel Gross, St. Martin's Press, 2022) is a book about discovering (and hiring) talent. Most highly sold books about hiring are rather about being hired, whereas Talent is primarily about the opposite problem. Talent comes in all shapes and sizes, so this book is attempting something harder than a book that tries to prepare for a particular kind of interview (like a software engineering interview), Talent aims to be relatively general in the observations it makes.

(I)

Working towards its goal, the book blends academic research and the personal experience of the authors. I've been thinking lately about the relevance of academic research for real-life practical decision-making in various domains (See section 1 here), so I'd be intrigued to know what the book would have looked like had the authors just written from their (extensive) experience evaluating talent, and seeing how that matches research (I suspect the book would be relatively unchanged). Personal experience is underrated, and the authors are reasonable enough not to discard their personal knowledge if it conflicts with a particular research literature.

In succeeding at explaining what sort of things to look for when finding top talent, the book also succeeds as an example of the fundamental importance of tacit knowledge in making these decisions. Intelligence matters, but far from exclusively! You want conscientious candidates, but not always. You might actually want to hire a subclinical schizoid as a consultant to generate interesting ideas, but not as a manager. And different people may present differently in an online vs an in person interview. Some may express themselves poorly when speaking but be extremely clear writers and thinkers.

One can't overcome the problem of tacit knowledge transmission with a book, if one reads the book 10 times, one would still not become a skilled judge of talent, so think of this book as pointing out what sorts of things to pay attention to, as a book on photography might point out how color, perspective, and composition go into making a picture that looks good, but one still has to get out there and take some pictures to learn how to take great photos.

It's also a book that is refreshingly aware of the meta-game1 it exists in: If you tell your audience to use this or that interview question then candidates will learn about those and craft polished answers that will hinder the interviewer's ability to see what's there. But Cowen & Gross see through this: they discuss tactics like repeating a question asking for more examples exhaustively. Moreover they remind us not to obsess about specific questions or interview formats, but rather it seems the book is an argument to get us to become the kind of person that just naturally sees talent there where it is. Another of the questions, "How did you prepare for this interview?" is also another great example of breaking the fourth wall of the interview setting, helping reach the actual person that's behind the potentially staged performance.

The core of the book will seem unsurprisingly correct to a lot of the audience; the interesting bits are various aspects of someone's character that the authors point to and that should be salient to talent-choosers: For example we shouldn't just look at a candidate, but at their trajectory. Are they learning fast, or are they stuck at the same level of performance they have been for a few years? Two individuals that have the same current job position can be radically different in what to expect from them in years to come.

Indeed, the book is a long exercise of "overrated or underrated":

Gregory Washington: How can society get better and finding talent and why is it so difficult?

Tyler Cowen: I think it’s so difficult because it’s not about fixed rules, it’s not about “Always hire the person from this school,” or “Hire the person who wears this kind of shoes.” I think it’s closest to music or art appreciation – so you can’t boil that down to fixed rules either, but if you spend a lot of time studying music or art, or some other areas, you can become much better at it. But there are never fixed rules for what’s a great symphony or what’s a good pop song.

GW: Is that really true?

TC: Yes.

GW: But there are some rules…

TC: There are… they’re not rules. There are principles. They all have exceptions, but I think that when it comes to talent, for most jobs we actually overrate the importance of intelligence, we underrate the importance of values, and we underrate the importance of what I call durability: the dedication to mission, to one’s self, and the ability to keep on going… It depends on the job you’re hiring for, but some of the lessons that I try to teach people are to look for those qualities…

That last aspect, durability is one worth expanding on. Durability is not quite grit, which seems to be just a strong correlate of conscientiousness. Rather the key idea goes back to this post from Robin Hanson: stamina. You may be able to work super hard and in a very focused way, but for how long? A PhD student friend, besides the long hours of lab work, also has the time to run a community of fellow biology enthusiasts, meet with lots prospective PIs for rotating into their labs, and find excellent raccoon memes. She sleeps 4-5 hours. Other people find it hard to wake up, and when they do it is very late, or get very drowsy when it's not even 10pm. If you compare a person that works 8 hours a day because that's all they can manage with someone that can put 16 hours into it because they are not tired you have, for the same intelligence, creativity, and whatever else, someone who is twice as productive. Even if someone has a few extra IQ points, it is hard to compete with someone that puts in twice the working hours you do. This is not an argument for burnout, it is just the observation that some people have a naturally very well aligned work-personal life, and that is valuable from an employer's point of view.

(II)

What is talent? This is not defined in the book, but one can only suppose that "you know it when you see it". The book spends a nontrivial amount of time looking at correlations between various variables and income. Doing this makes sense if you think that talent is rewarded by the market (To what extent is the book focusing on finding talent that can make you succeed financially?), but this is far from general: if we take talent to be someone that generates something of high value, those that are talented producers of public goods will be at a disadvantage regarding earnings. Among them, academics are the chief example of an extremely smart, and yet not particularly well paid group (Though this seems to be changing: If you are a top-tier CS or life sciences researcher you can get to million-dollar salaries these days). Academics are playing a game that's different from making the $ number go up. If one could separate the Gross and the Cowen2 -flavored parts of this book I suspect that this is a very Gross-inspired section: Academics and founders of great companies are two different kinds of people. "How strongly do you want to win?" only makes sense after defining what game are you playing. But there's a certain kind of talented person that prefers to imagine new games to play, rather than finding opponents to beat. Michael Nielsen has this memorable tweet that perfectly serves as a counterpoint to the focus on earnings of some chapters. Michael is the kind of talented person Emergent Ventures would be interested in, but Pioneer qua venture capital firm would not.

Similarly, whereas the book observes that hierarchy-savvy Vox founders Ezra Klein et al. launched a successful website, other bloggers stayed in their parent's basement in sweatpants writing intriguing posts. And yet it is internet besserwisser Gwern, and not the Voxers who Daniel Gross follows on Twitter. Gwern is winning, but not at the moneymaking game. Gwern plays his own game and despite my efforts to the contrary, he exists in a leaderboard of one.

This assessment I just made here seems somewhat accusatory, but I don't mean it in that way, I just want to broaden your idea of what talent is. And there is a case to be made that for many sets of values a person may hold, metaphorically taking over the world is the best way to actualize those values. If one cares about community, one can start a grouphouse, or one can start a social movement for co-living leading to thousands of new houses starting. If one cares about learning, one can obsessively blog for years, or one can try to start a research organization. You can also start an unrelated company inbetween, then use the proceeds for the latter. Maybe Gwern should try to become a billionaire and then discover and enable the next billion Gwerns.

(III)

Recently, one of my favorite questions to bug people with has been “What is it you do to train that is comparable to a pianist practicing scales?” If you don’t know the answer to that one, maybe you are doing something wrong or not doing enough. Or maybe you are (optimally?) not very ambitious? (Marginal Revolution, 2019)

There's a similar question in the book. When I read it, I had no answer. I would have shrugged and say "I don't know" in person (which is a bad answer, according to the book). There are things I certainly do (sure I read, and write this blog) but not that purposefully as a means of self-improvement. Maybe I have internalized the ethos of self-improvement so much that despite being working all day I don't immediately think of that as a vehicle for self-improvement.

Piano scales are finger workouts for pianists: not only but strength and dexterity but in all muscle memory, and perhaps understanding of how sounds work together.

This doesn't have a direct analogue for knowledge work, brains don't seem to get as rusty as unused fingers. Once you're good, you're good. The one thing that decays is intelligence (Can't do much about it other than trying to stay healthy), and memory (Where you could use spaced repetition or take notes, none of which Tyler does). Indian ragas are great but I'm not so convinced they help with other kinds of skills. Transfer learning is hard!

The act of writing itself also requires some finger dexterity and speed at typing, but good writing is more constrained by good thinking, I find, than speed of typing, and I can type relatively fast (80-100wpm) without having tried to get particularly good at it, besides typing a lot. But this is not the constraint in my writing, so I don't try to practice typing.

There's an obvious thing that gets you to improve: Doing the thing you're trying to do. The reason that training exists is to break down the main activity you want to get better at into chunks that can be more easily practiced. Chess players get better primarily via solo practice, not playing a lot of chess (The book discusses a similar example). Can we learn from the way chess players learn and apply that to talent search?

As discussed in the linked blogpost, chess learning proceeds by memorization of patterns and the formation of chunks in memory to aid efficient recall. Playing chess is less effective than practice because once one has worked through an opening book, the starting of any future chess games are adding little new learning. Instead, with chess problems, one can focus on specific weak areas and learn examples in a context where learning is needed. I somewhat believe that reading a lot of business books (biographies, corporate histories, and books on management techniques) can teach something about management. Interviewing and meeting talented people can improve one's skill at identifying talent (The book suggests to jumpstart this process by watching the right TV shows, which I endorse). But these are far removed from the equivalent of mental piano scales, they are very close to playing piano all day.

On reflection, the self-improvement question gets at another important piece of information: What is the candidate trying to do? Do they have clear aims? Those more in an "exploit" (vs "explore") phase will tend to have clearer answers to the question.

(IV)

Trying to crack cultural codes is another recommendation I'm more skeptical of as a means of talent spotting excellence, with some caveats. As much as the authors ended up agreeing enough to write a book, I don't quite see Daniel Gross embracing the cracking cultural codes admonition to the extent Tyler does (Though Daniel doesn't write that much so who knows). Is this because he's cracking a different set of cultural codes (videogames?), or because he does not think that is useful for what he does? I definitely don't try to do much in terms of cultural code cracking, though I have my set of niche music I listen to, and I'm always looking for more, but just for my own enjoyment.

One interpretation of why this may work is that learning about, say, Indian culture could help better understand Indians, and thus find talented Indians. Likewise when working with people from other cultures, knowing about their culture may make communication easier. But how much of this does one have to do? Tyler does go very deep into cultural code cracking. That time could be also spent reading longevity research papers, doing more interviews, reading blogposts from talented people that one wants to hire, or networking at local events.

Appendix: IQ and job performance

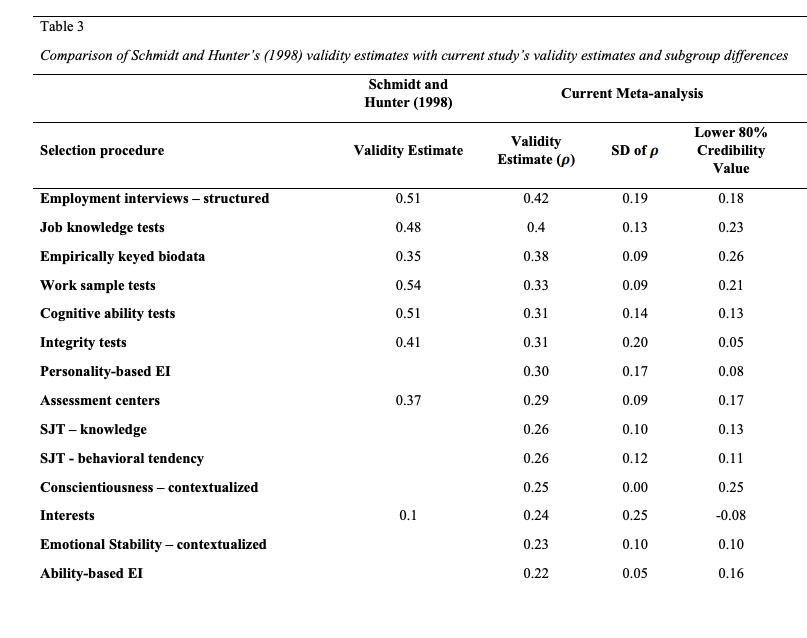

Back in the day I might have gone around checking all the references, but these days I care more about the directionality of the argument: even if a paper is wrong, the overall argument can still be correct. This is why this section is in the appendix and doesn't add to the main review. There was only one paper that seemed to contradict my priors sufficiently for me to go check it: Does IQ really predict job performance (Richardson & Norgate; 2015). Cowen & Gross say:

There is also a sizable academic literature on intelligence and job performance. The most measured and thoughtful study is by Ken Richardson and Sarah H. Norgate and is titled "Does IQ really predict job performance?". IQ need not be the same thing as general intelligence but the researcher's conclusions are pretty sobering: "In primary studies such correlations [between IQ and job performance] have generally left over 95% of the variance unexplained"

Moreover, in the relevant citation, the authors point to the broad literature (implying a broad survey was done), adding one additional reference to interpret the existing studies: Byington & Felps (2010), which is suggestive, but I think ultimately wrong, ignoring other sources of evidence that reinforce the model where the IQ-performance correlation is free from the hypothetical mechanism described in the paper (e.g. IQ also predicts video game performance).

I wanted first to state those priors, derived from the work of Stuart Ritchie (whom I trust in all things intelligence), and who summarized the state of the art some time ago (Ritchie, 2016).

The Richardson paper was written before the book, so my prior here is that Stuart was aware of it, but discounted it; though the book does not make a direct reference to it. Note also that even in the "smart person consensus" where IQ does matter, the extent to which it matters is "a lot" but not totally, and that correlation is smaller for leadership, which is character type (the founder) that the books focuses on, so in practice the book is making a minor correction to a broadly valid point.

What does the Richardson-Norgate paper say? First, the paper does note that there are multiple issues with measuring job performance and its relation to IQ. What is even job performance, and can we aggregate across domains? If we use supervisor scores, maybe those are biased. The original studies that go into the meta-analyses that the figure above comes from, the "primary studies" the quote refers to find smaller correlations, and then the meta-analysis correct for a variety of potential sources of errors, arriving them at the ~0.5 correlation that Cowen & Gross are skeptical of. Moreover, at the end of the paper it is also noted that even taking the literature at face value, even the 0.5 correlation implies that 75% of the variance in job performance is unexplained anyway; the question would there be where there are other traits that are as good as IQ that we should pay attention to, or whether that 75% is mostly noise, and we should still take our best guess based on IQ. The actual quote in Talent, referring to 95% of the variance unexplained refers to these primary studies prior to their inclusion in a meta-analysis, and without corrections. Are these corrections fair? And what do these original studies look like? It does seem a bit of a stretch to extrapolate from, say, the IQ-job performance correlation in "retail food manager, fish and game warden, biologist, city circulation manager" (Table 1) to the IQ-job performance correlation in startup founders. So one could accept the literature at face value, but then sweep it aside, because it's not that informative for the domain at hand.

From here, one could proceed to spend a few days delving into the relevant literature, playing methodological ping pong, finding flaws and then arguments for why those flaws are not fatal and then counter-counter arguments, talking to some experts and assessing who is right and that's what I would have done a few years ago but now I'm more pragmatic: Will the fact that the correlation is 0.5 instead of 0.2-0.3 change my actions if I were hiring? The entire range 0.2-0.5 maps to "Intelligence matters for job performance, but not only" so we can continue to believe that. The exact number doesn't seem very important. Certainly if the numbers were more extreme like <0.1 or >0.8 then maybe we would want to select almost exclusively based on intelligence in general, but this is not the case. Similarly, if this research literature was more specific (Say, we could be sure that the number is 0.3 instead of 0.5 for founders in particular) then we would put more weight on it and it would matter more to figure out the right number.

As it happens, the last review I could find, Sackett et al. (2021) puts the correlation at .31 (vs .51 in the original studies).

Given that even the measure that ranks as the best (structured interviews) is far from ideal, one could make here the argument that it may be efficient to give up on trying to squeeze the lemon too hard, and hire randomly candidates that are above a certain threshold, in the same vein to proposals to fund science by lottery.

Appendix: Reference checks?

The book has a section on how to get references on your talent. A common part of many interview processes is asking for a candidate to submit the names of colleagues and ideally managers to ask them about the candidate. The book accepts the premise of getting references (As does say the High Growth Handbook, and Marc Andreessen), and has some tips on how to go about doing that, but I remain convinced that references are not that useful. The combination of prior information (the whole interview) with sugarcoating on the colleague's side makes it very uncertain what good quality information you get from these. There are situations where references can help spot a bad candidate: indeed if the candidate is unable to produce any, that's a red flag. Can't these candidates be spotted earlier in the interview? How common are these people? There is some information gained from the referencing process, but some velocity lost in waiting for the reference checks, as well as time consumed by reaching out to the referees. My baseline recommendation is to skip the checks, but they may make sense in a context-dependent way. Ideally we would hear more from proponents of reference checks, having a number of case studies, or some statistics on how frequently they drive hiring decisions would be useful.

Unfortunately we have to rely on non-academic information to make these decisions: The latest review on job performance prediction gives up on reference checks due to lack of information to assess how well they work.

[EDIT 2021/02/12] Armand Cognetta pointed out to me that reference checks serve other functions, even when one agrees with the basic premise that the reference, once obtained, will be usually favorable to the candidate. Asking for references, especially if one asks for many of them (Say 9!) tests how much of a network a candidate has, how resourceful they are, and how much they are interested in the job (How quickly can they get those references). Another, less obvious benefit, is that the reference checks are built-in networking! You end up meeting new people that you may want to reach out to at a later time. It is key to ask questions that prompt some potential negatives (To avoid the initial expected positive bias towards the candidate): A question like "On a scale from 0 to 100, where 100 is doing this job perfectly, above and beyond, where would you put person X" will probably get a nice but not perfect answer like say an 85. Then one can ask why not 100, and that may lead to some potential minor negatives.

Comments