Better Science: A Reader

If you've been following Nintil -or been moderately curious1- you have probably come across claims that Science is broken in some way or another, that we live in an era of scientific stagnation, or some horror stories about researchers spending their lives applying for grants and not doing research. Here's a reading list that you may find interesting to navigate this conversation. Each piece includes a brief fragment from the source that describes its content. This is not intended to be a collection of every paper I've come across, but of some that I consider relevant.

At the moment this just has readings for one topic, but I intend to progressively add other topics, like peer review, alternative funding schemes, replication, open science, tools for science, and more.

If you have any suggestion, please do send them to [email protected]

General information

Turn the scientific method on ourselves

We inherited the current institutions of science from the period just after the Second World War. It would be a fortuitous coincidence if the systems that served us so well in the twentieth century were equally adapted to twenty-first-century needs. Experimenting on ourselves may well lay bare some shortcomings of the scientific community and expose us to criticisms from politicians, who are always looking for excuses to cut science funding. But the only alternative to such controlled experimentation is the gradual stultification of our most cherished scientific institutions.

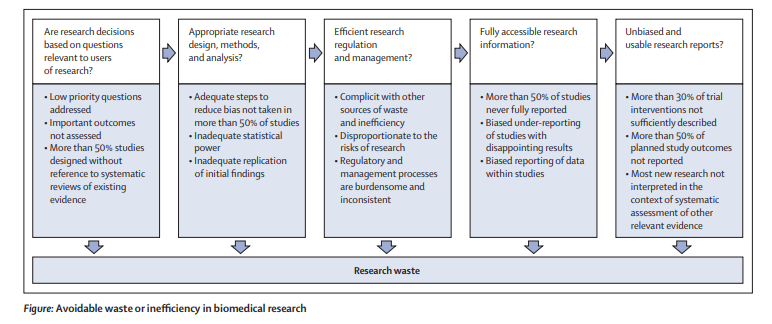

How to increase value and reduce waste when research priorities are set

The increase in annual global investment in biomedical research—reaching US$240 billion in 2010—has resulted in important health dividends for patients and the public. However, much research does not lead to worthwhile achievements, partly because some studies are done to improve understanding of basic mechanisms that might not have relevance for human health. Additionally, good research ideas often do not yield the anticipated results. As long as the way in which these ideas are prioritised for research is transparent and warranted, these disappointments should not be deemed wasteful; they are simply an inevitable feature of the way science works. However, some sources of waste cannot be justified. In this report, we discuss how avoidable waste can be considered when research priorities are set

How to think scientifically about scientists’ proposals for fixing science

My focus here will not be on the suggestions themselves but rather on what are our reasons for thinking these proposed innovations might be good ideas. The unfortunate paradox is that the very aspects of “junk science” that we so properly criticize—the reliance on indirect, highly variable measurements from nonrepresentative samples, open-ended data analysis, followed up by grandiose conclusions and emphatic policy recommendations drawn from questionable data— all seem to occur when we suggest our own improvements to the system. All our carefully-held principles seem to evaporate when our emotions get engaged. This is similar to a pattern noted by Gelman and Loken (2012) that academic statisticians only rarely seem to use statistical principles in designing and evaluating their teaching.

Is 85% of health research really "wasted"?

Our estimate that 85% of all health research is being avoidably “wasted” [Chalmers & Glasziou, 2009] commonly elicits disbelief. Our own first reaction was similar: “that can’t be right?” Not only did 85% sound too much, but given that $200 billion per year is spent globally on health and medical research, it implied an annual waste of $170 billion. That amount ranks somewhere between the GDPs of Kuwait and Hungary. It seems a problem worthy of serious analysis and attention. But how can we estimate the waste?

Biomedical research: increasing value, reducing waste

Quantifying and reducing time spent in applying for grants

Time writing a grant is time not spent doing research. Some have argued that this is not all that big of a problem because time spent writing a grant helps clarify one's ideas. There is also the time delay in starting a new project.

The impact of improving this depends crucially on the role of the PIs, and the size of the lab. If a lab is big, then the time spent by the PI applying for grants is amortized among all lab members. If a lab is say 60 people and 100% of the 1 PI time is spent on grants then freeing up that time would lead to an improvement in man-hours of 1.7%; while if the lab is smaller, say 6 members then we would get 16.7% more man-hours of science done. This all assumes the hours worked by PIs, graduate students, postdocs and other lab members count the same. If this is not true (And it wouldn't be if PI's time put to do research can yield more interesting ideas) then the assumption wouldn't be true; and in that case it may be better to think of two components here, one is the generation of novel ideas and the other is the actual doing of the experiments. But even in this case, if the PI value add as a scientist is interesting ideas one can imagine producing the ideas for the rest of the lab to expand on may do as much as if they were fully involved in the research process. Be that as it may, here are some readings:

On the time spent preparing grant proposals: an observational study of Australian researchers

An estimated 550 working years of researchers' time was spent preparing the 3727 proposals (95% CI 513 to 589 working-years). Based on the researchers' salaries, this is an estimated monetary cost of AU$66 million per year, which is 14% of the NHMRC's total funding budget. Each new proposal took an average of 38 working days of the researchers' time and resubmissions took an average of 28 working days: an overall average of 34 days per proposal. Lead researchers spent an average of 27 and 21 workings days per new and resubmitted proposals, respectively, with the remaining time spent by other researchers.

How much time do scientists spend chasing grants?

The biggest surprise is how much time I have to spend getting funding for my research. Although it varies a lot, I guess that I spent about 40% of my time chasing after funding, either directly (writing grant proposals) or indirectly (visiting companies, giving talks, building relationships).

Streamlined applications were shorter but took longer to prepare on average. Researchers > may be allocating a fixed amount of time to preparing funding applications based on their expected return, or may be increasing their time in response to increased competition. Many potentially productive years of researcher time are still being lost to preparing failed applications.

To Apply or Not to Apply: A Survey Analysis of Grant Writing Costs and Benefits

As noted in a 2008 AAAS report [10], “One-half of [NSF] new investigators never again receive NSF funding after their initial award.” Some of our survey respondents remarked on this explicitly, writing “I applied for grants from the NSF in 2004, 2005, 2006 and 2007. … Most of the reasons given for not funding were that funds were too tight that particular year and that I should reapply the next year since the proposal had merit… I finally just gave up.” Or “I ceased to apply for grants as a PI after 2007 when—after much experience—I decided that applying for federal grants was not a good use of my time”. A research-active department head wrote, “I don't feel that it is worth my time to apply.” [...] . We note that 20% funding rates impose a substantial opportunity cost on researchers by wasting a large fraction of the available research time for at least half of our scientists, reducing national scientific output, and driving many capable scientists away from productive and potentially valuable lines of research.

A time allocation study of university faculty

To the best of our knowledge this paper is the first systematic effort to examine the effect of tenure and promotion on the disaggregated time allocation of university faculty. [...] One might conclude that tenure is detrimental to a research university because faculty reduce their time allocated toward research and grant writing, those activities that, in general, are associated with the ethos of a research institution.

Using democracy to award research funding: an observational study

An alternative funding system that could save time is using democracy to award the most deserving researchers based on votes from the research community. We aimed to pilot how such a system could work and examine some potential biases. [...] Extrapolating to a national voting scheme**, we estimate 599 working days of voting time (95% CI 490 to 728), compared with 827 working days for the current peer review system** for fellowships. [..] There were many negative comments about the idea of using democracy to award funding. Concerns were raised about vote rigging, lobbying and it becoming a popularity contest as typified by this quote I’m curious how this approach is intended to be anything other than a popularity contest, benefitting those who have already become ‘names’. Particularly, how will this help early career researchers, who are most disadvantaged by the current system?

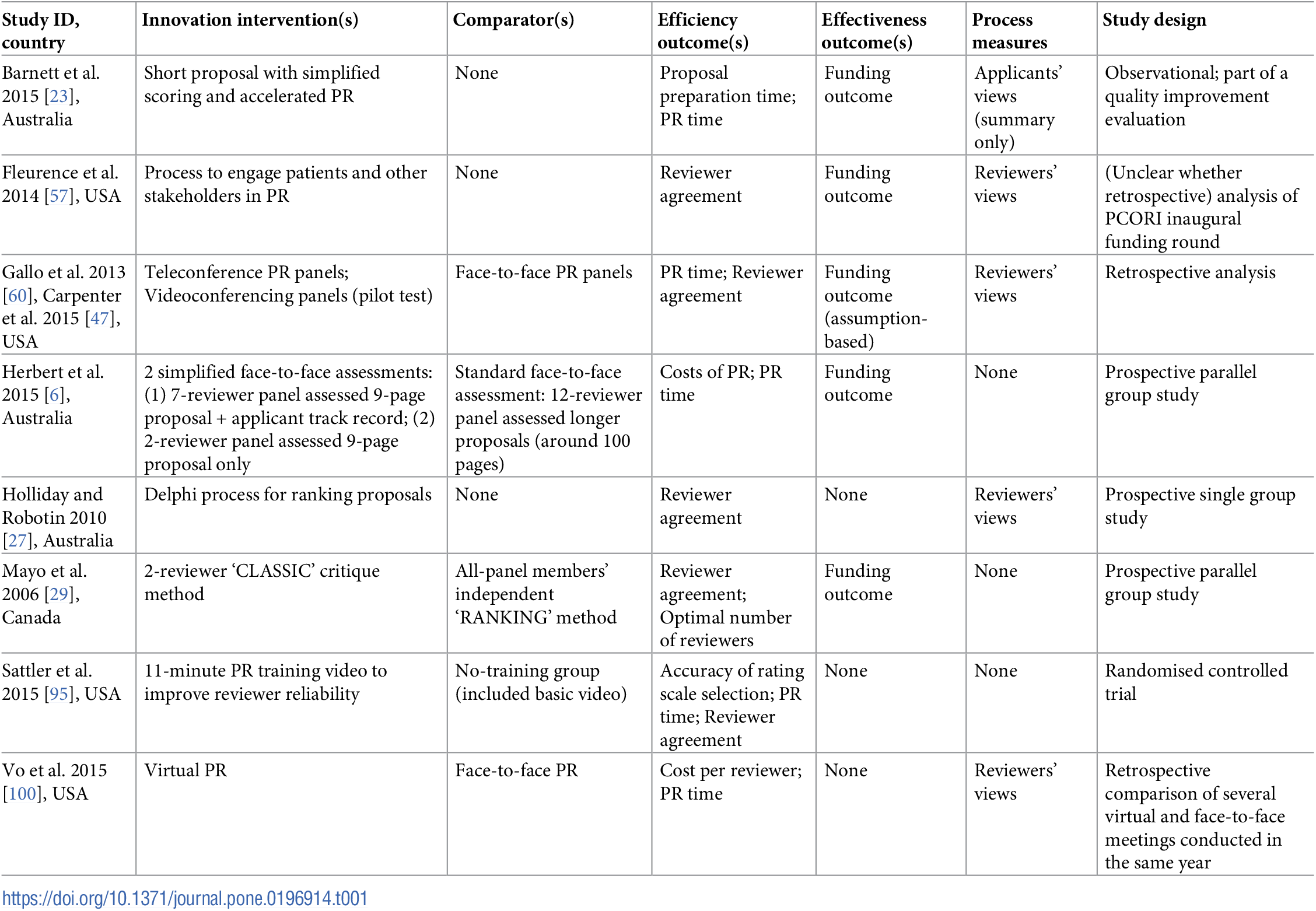

This is a review of various interventions that have been proposed to improve the grant application process

In which case you would be reading Nintil anyway, obviously.

Citation

In academic work, please cite this essay as:

Ricón, José Luis, “Better Science: A Reader”, Nintil (2020-05-19), available at https://nintil.com/better-science/.