The Soviet Union: Productive Efficiency

[Part of the Soviet series]

How efficient was the Soviet Union at producing stuff? Why?

This post has its origin in reading two articles, that you can find here and here, that among other things, claim that the Soviet Union was, contrary to common knowledge, efficient:

Around the time of the Soviet collapse, the economist Peter Murrell published an article in the Journal of Economic Perspectives reviewing empirical studies of efficiency in the socialist planned economies. These studies consistently failed to support the neoclassical analysis: virtually all of them found that by standard neoclassical measures of efficiency, the planned economies performed as well or better than market economies.

Murrell pleaded with readers to suspend their prejudices:

The consistency and tenor of the results will surprise many readers. I was, and am, surprised at the nature of these results. And given their inconsistency with received doctrines, there is a tendency to dismiss them on methodological grounds. However, such dismissal becomes increasingly hard when faced with a cumulation of consistent results from a variety of sources.

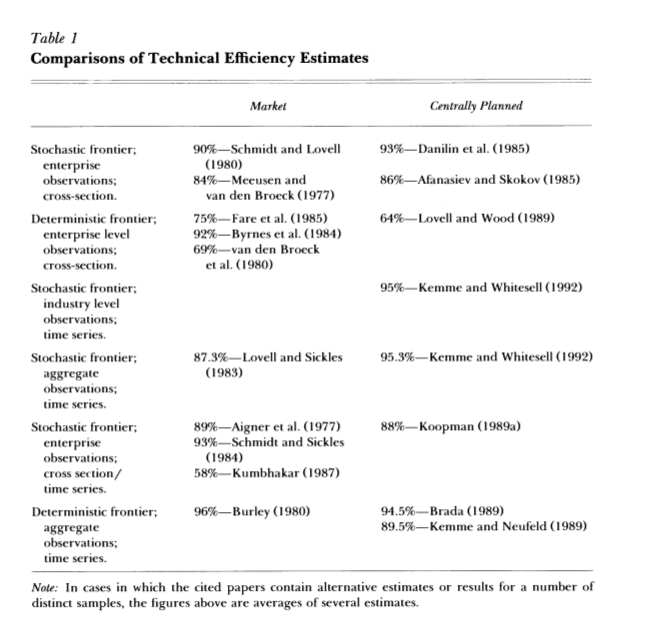

First he reviewed eighteen studies of technical efficiency: the degree to which a firm produces at its own maximum technological level. Matching studies of centrally planned firms with studies that examined capitalist firms using the same methodologies, he compared the results. One paper, for example, found a 90% level of technical efficiency in capitalist firms; another using the same method found a 93% level in Soviet firms. The results continued in the same way: 84% versus 86%, 87% versus 95%, and so on.

Then Murrell examined studies of allocative efficiency: the degree to which inputs are allocated among firms in a way that maximizes total output. One paper found that a fully optimal reallocation of inputs would increase total Soviet output by only 3%-4%. Another found that raising Soviet efficiency to US standards would increase its GNP by all of 2%. A third produced a range of estimates as low as 1.5%. The highest number found in any of the Soviet studies was 10%. As Murrell notes, these were hardly amounts “likely to encourage the overthrow of a whole socio-economic system.” (Murell wasn’t the only economist to notice this anomaly: an article titled “Why Is the Soviet Economy Allocatively Efficient?” appeared in Soviet Studies around the same time.)

And

William Easterly and Stanley Fischer’s World Bank study of the ‘Soviet climacteric’ argues that Soviet R&D on civilian production actually increased substantially between 1959 and 1984, rejecting the common notion that the Soviet arms race combined with the inflexibility of Soviet production caused the consumer economy to come to a standstill.(3) Moreover, Brendan Beare’s correction of the Easterly and Fischer paper has demonstrated that due to statistical mistakes in the reconstruction of the data, the elasticity of substitution between capital and labor in the Soviet economy was much higher than is commonly believed.(4) In other words: previous scholars claimed that when the Soviet surplus population ran out, the USSR was unable to efficiently replace labor with machinery, leading to an inability to make the leap from labor-intensive to capital-intensive production. But Beare’s data show that the ratio of this replacement of labor by capital may not have been as bad as previously thought, but in fact may have been quite high, as it was in Japan, which did not experience such stagnation. Nor did investment itself falter: even as late as 1989 the Soviet investment share of GDP was a staggering 35%. In short, Soviet central planning did not fail due to its inability to develop or implement labor-saving technology.

Why do I mention all these technicalities? Simply to make the important point that the traditional narrative, in which the Soviet central planning model collapsed due to the inherent flaws in such a system’s ability to expand and deliver the goods, is untrue. The failure of Soviet and Eastern European planning is no less real than it was before, but it must be understood as a contingent, political failure, located not in the concept of central planning itself, but in the limitations of the Soviet version. By most statistical measures, even those of outright foes of the Soviet Union, their central planning system was an overwhelming success in terms of growth, increases in productivity, and raising the potential living standards. It is not a coincidence that the USSR was the only state ever to make the American ruling class tremble – no mean achievement. Contrary to Ackerman however, I would argue its ultimate failure rested not so much in these categories. It failed for reasons not dissimilar to the flaws of Ackerman’s market socialism. The Soviet Union failed not because it was too socialist, but because it was not socialist enough.

While there is a grain of truth to the statements contained in the quotes regarding efficiency, those two essays convey wrong ideas to the reader. As we will see as we discuss the literature regarding efficiency in the Soviet Union, both posts misinterpret the evidence in ways that were already pointed out a decade ago, including in the same papers that they cite.

(I) Efficiency, some definitions

Efficiency can mean many things in economics. The term generally refers to how much of one thing you can extract out of another, relative to some optimal amount. The term is thus used in the same was as in engineering. We can distinguish between several types of effiency (Escoe, 1996) :

- Economic efficiency: Concerns the ability of an economy to produce what is demanded from it. This is, producing the right goods, at the right time, in the right amount. (Or producing at the desired point in the appropriate n-dimensional Production-Possibility Frontier (PPF)). We can divide it into:

- Static efficiency: How close to the PPF the economy is at a given point in time.

- Dynamic efficiency (Balassa, 1964): How fast the PPF expands.

- Allocative efficiency: Concerns the ability of an economy to efficiently allocate inputs. An economy is allocatively efficient if given a level of technology, no gains can be made if productive factors are shifted around (Or, that the marginal rates of technical substitution (MRTS) for the inputs are equal in every possible use). An economy can be allocatively efficient and yet be inside the PPF, due to technical inefficiency.

- Technical efficiency: Concerns the ability of an economy to produce the outpt one would expect from its inputs and technology level, relative to some standard (With respect to a relevant PPF). Some authors take the PPF to be at the level of the country, others at the level of an industry within a country, and others (see Bergson, 1992), an international PPF.

- Total Factor Productivity (TFP): Ratio between output and a weighted function of inputs (Capital and Labour). It is not exactly a type of efficiency, and it is used to measure how much growth is not due to variations in inputs. Which typically is taken to mean how well the economy is making use of those resources. Sometimes TFP growth is confused for some sort of rate of technological improvement, but it is not. TFP is calculated as a residual, and everything that affects how well an economy converts inputs into outputs will be captured by it.

- X (GDP, tonnes of steel, etc...) per Y (worker, man-hour person...), again not exactly a type of efficiency, but gives an idea of how productive Y is in terms of X.

Now you can see why the paragraphs quotes are incomplete. To gain a full understanding of productivity in the Soviet Union (and other socialist economies) we need to study all of the productivity types, and see why are the way they are.

(II) X per Y

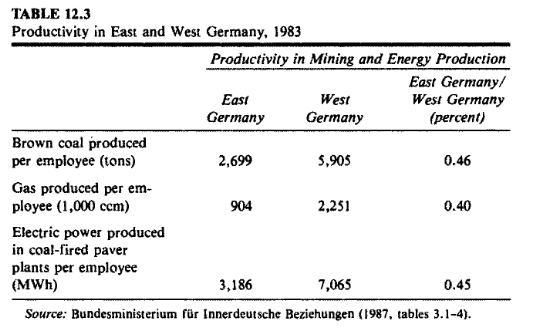

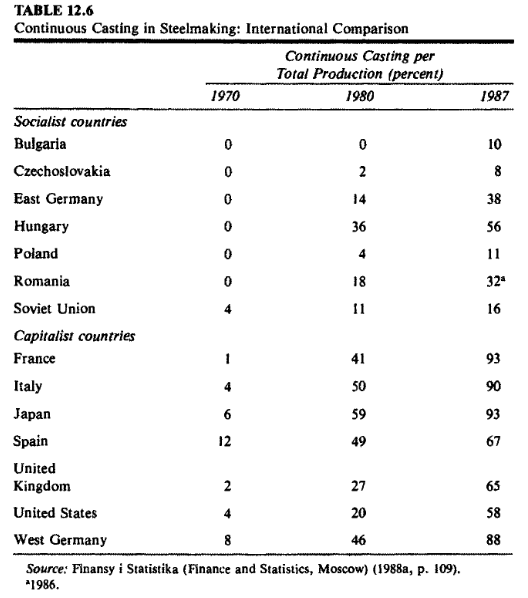

Let's start by what is perhaps the most intuitive indicator. For that, I have two tables from The Socialist System (Kornai, 1992):

Yes, Germany is not the USSR, but I think it serves as a first approximation. One possible explanation for this particular table is overmanning: Employing more people than necessary for a variety of reasons explored in the linked post. Other explanation is a lower level of technological development.

The second table is here just because it comes from the same source :) . It shows how fast a given technology diffuses through the economy. In 1970, the Soviet Union was matched with Italy and the United States in their fraction of continuous casting of steel. By 1980, the US has multiplied their fraction by 5 and italy by 12.5, while the USSR just increased by a factor of 2.75. From 1980 to 1987, the US dominated with an increase of 2.9 followed by Italy with 1.8, and finaly the Soviet Union with just 1.45. The US took more time than, say, Spain or Italy to diffuse this innovation through its steelmaking industry, perhaps due to the presence of a larger steelmaking industry that would be more difficult to upgrade. Given this, we would expect the USSR to get a bonus from having much lower GDP compared to the US. Or you could say that we should look at the actual amount of steel being made in each country, and that maybe more was being made in the USSR, but no. (See this CIA report, Appendix C for hints that it wasn't the case)

(III) The reliable scribe vs the unreliable printing press: Static & Dynamic efficiency

Imagine you have to copy a text and you can choose between asking a scribe to do it (manually), and using a printing press (assuming its a new invention). In world A, the scribe, having been doing the same thing over and over for decades, never gets a book wrong.

In world B, scribes are replaced by newer technologies. The printing press and its operators print faster, but on the other hand, sometimes they make mistakes, and have to start again.

The scribe captures the property of static efficiency: doing something efficiently at a given point of time, while the printing press captures the idea of dynamic efficiency and its relation to static efficiency. The printing press is in some sense more efficient than the scribe (More books per hour), yet individually, it is less statically efficient than the scribe (The escribe transforms 100% of inputs into outputs, while the printing press does so with less than 100% of inputs, as there are mistakes).

Balassa (1964) [1] explains that this is what happens in capitalism and socialism. Under capitalism, technological innovation is faster, and so it is more difficult to learn to optimally use a technology before it is replaced by another one. Under socialism, slower change gives managers and workers time to adapt. Hence, there is an inverse correlation between static and dynamic efficiency, and we would expect to find a higher static efficiency in socialist systems (That will nonetheless be worse at long-term worse), and the opposite for capitalist systems.

Desai (1984) calculates allocative efficiency for the Soiet union (via measuring if the MRTS are unequal.) Two different datasets, from official Soviet sources and the CIA are used, and allocational loss is found to be around 3-10%. In both datasets, covering from 1955 to 1975, this inefficiency is shown to be increasing, and the different between both datasets is not substantial.

Danilin et al. (1985) study a sample of cotton refining enterprises in the USSR (Only one sector, bear in mind), and they find high technical efficiency with little variation. This high technical efficiency is with respect to the highest technical efficiency attained in the sector in the USSR, so as the authors remark, this is compatible with a low overall level of technical efficiency when compared to Western countries. We'll go back to this study a couple of times later on.

We now get to two of the most important papers in the literature, written by Robert S. Whitesell in 1985 and 1990. The first paper first presents the consensus case for Soviet decline: a combination of decreasing growth in TFP and progressively lower marginal returns to capital. But, he says, that theory has not been thoroughly contrasted with empirical data. And that's what he does, for the USSR, Poland, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, and Yugoslavia. The first four have a Soviet-type economic system, Hungary is said to differ in some sense from the USSR, and Yugoslavia has a system that is based on worker management of industrial enterprises. For completion, both Cobb-Douglas (Constant returns to scale, unitary elasticity of substitution, and a variable rate of Hicks-neutral technical change) and CES production functions are used in the analysis. In addition, a second set of functions with constant Hicks-neutral technical change are also estimated.

Essentially, if high elasticities of substitution are found, it will mean that the rising amount of capital in the Eastern countries will not slow down growth as one of the slowdown theses suggests.

The estimates for the elasticities, once calculated, suggest that they are around one in the studied countries, except in the Soviet Union. The rate of TFP growth is found to be constant in Poland, East Germany and Yugoslavia, increasing in Hungary, and decreasing or constant in the Soviet Union or Czechoslovakia. So, Whitesell concludes, the slowdown in these countries is not due to low productivity growth or diminishing returns to capital, but a slowdown in the rate of growth of inputs. In the case of the USSR, the results indicate that both causes may be at play. And thus the conclusion,

There is no indication in the results of this study that the Soviet-type economic system imposes technological constraints on industrial growth that are identifiable through the parameter estimates of aggregate production functions. The estimates indicate that for most of Eastern Europe, including Yugoslavia, the simple Cobb-Douglas production function with constant technical change and constant returns to scale is the best description of growth, and that the primary cause of decreasing industrial growth has been a decrease in the rate of growth of factor inputs. The Soviet Union is the only country that deviates significantly from this result. Although decreasing input growth has occurred, it is not the major cause of Soviet growth retardation. There is a clear indication that either decreasing factor productivity growth and/or diminishing returns to capital are more important causes. These results imply that the similar sectoral growth pattern may be caused by priorities imposed by ideological or practical considerations, but are not the result of a systemimposed technological structure. This is further supported by the unique pattern of factor productivity growth in Soviet industry.

Whitesell attempts to explain the why of this difference between the USSR and the other countries: perhaps it is because these other countries are smaller in area and population, and thus easier to central-plan. Or perhaps it is because Eastern Europe depends more on foreign trade than the Soviet Union, and that forces them to be more compeitive. Or perhaps technological diffusion of Western advances is faster in these countries, precisely because of their size. [2]. Regardless, the overall conclusion, that the Soviet system itself doesn't 'impose technological constraints on industrial growth' didn't last long, as we will see in the studies following.

That the Soviet Union has problems in adopting and diffusing new technologies and in improving the mobility of resources is not new. What is interesting is the implication that the other Soviet-type systems of Eastern Europe may have an advantage in this regard. Greater dependency on foreign trade may mitigate the stagnating influence of the Soviet-type economic system by requiring a more flexible response to the world economic environment, which requires a more receptive environment to technological innovation and input substitution.

The next paper, Why does the Soviet economy appears to be allocatively efficient (Whitesell, 1990), starts in a way that might sound friendly to supporters of socialist systems:

Despite the conventional wisdom that the Soviet economy is inefficient in every dimension, there is a rather large mount of statistical and econometric evidence that some aspects of the Soviet economy may be allocatively efficient relative to market economies

Ideal for cherrypicking quotes! But then, he continues,

This paper argues that econometric results showing Soviet allocative efficiency do not refute the conventional wisdom of poor Soviet economic performance, but in fact are completely consistent with such an evaluation.

Like we have explained above, Whitesell differentiates between allocative and technical efficiency, and focuses on the former, which does not imply anything about the latter. In his literature review, he goes back to Dalinin's study of the cotton industry in the USSR. Dalinin's conclusion was that technical inefficiency was low (Roughly, factories were doing their best, given their technological means). But Whitesell contends that his results actually imply low allocative, not technical, inefficiency, in the sense he uses. The story is that, as Danilin also admits, the results are compatible with low absolute technical efficiency (compared with the West); and so the results just show that resources are being properly allocated between cotton factories.

'Technical' inefficiency in this estimation is defined only relative to the least technically inefficient firms. If those firms which define the frontier are very inefficient relative to some absolute or engineering conception of the production function, then this estimation process is unable to perceive that fact. So the estimates do not demonstrate technical efficiency in this absolute sense. The estimates do show that productivity differentials across firms are small. This implies allocative efficiency in the sense that resources are being allocated in this industry such that cost differentials are small. If firms face the same prices, cost differentials will be small if marginal rates of substitution between inputs are similar in different firms and if firms have similar levels of technical efficiency.

And his conclusion is the same we already saw in Balassa's paper. Oddly, Whitesell does not cite it, and neither doe anyone else in the literature.

We have argued that there is a positive correlation between the rate of economic growth and technological change and the size of static allocative inefficiency in all economic systems including the Soviet-type economy. The implication is that the finding of relatively high levels of static allocative efficiency in the Soviet economy is a direct result of its relative technological stagnation. Consider the evidence. It has long been known that the Soviet economy is characterised by a low rate of technological innovation. It is also well known that Soviet growth is primarily extensive, i.e., growth comes mainly from the expansion of inputs rather than from new technology.

Furthermore, by any measure, the dynamism of the Soviet economy has been rapidly diminishing. Output growth rates have been falling, the growth of labour productivity has been falling, and the growth of either capital or combined factor productivity has been falling. And these problems have accelerated since the mid-1970s. In fact, there is evidence that combined factor productivity growth has been zero, or even negative, since the late 1970s. If this is the case, then either there is no longer any new technology being introduced and diffused in the Soviet Union, or technical efficiency is falling so quickly that it is swamping the effect of changes in technology.

The interpretation most consistent with non-econometric studies is that some technological innovation is occurring but it is small, and that technical inefficiency is increasing. This interpretation also is supported by empirical findings of increasing overall inefficiency in Kemme and Whitesell. Soviet newspapers in the past three years give one the strong impression that Soviet economists and planners themselves believe that technical inefficiency has been increasing since the early 1970s. If the Brezhnev era was really the 'era of stagnation' then technical inefficiency is likely to have been increasing. Evidence includes: reduced pressure on firms to fulfil output targets; an increasing amount of plan revision in order to allow firms to fulfil plans ex post; expansion of black and grey market activities; increasing absenteeism; increased cynicism of workers toward the system; increasing inventories, etc.

Since the introduction and diffusion of new technology comes primarily from central planners, one can infer that there has been a decrease in the pressure to introduce and diffuse new technology as well. In addition, the reduction in the rate of growth of capital, and the change in the allocation of much of that capital from manufacturing industries towards agriculture, have probably reduced the rate of embodied technological change.

The evidence cited above implies that the Soviet economy is dynamically stagnant and that it has become progressively more stagnant through time, at least prior to the Gorbachev era. The statistical evidence cited in this paper implies that the Soviet economy is characterised by a high level of allocative efficiency and that allocative efficiency appears to have increased in the late 1970s and early 1980s, exactly the time when the dynamism of the economy decreased. In the model we have presented allocative inefficiency is positively correlated with the rate of growth and technological change. The implication is that the Soviet economy appears to be characterised by an unexpectedly small level of allocative inefficiency precisely because of its dynamic stagnation. Therefore, the finding of relatively high levels of allocative efficiency in the Soviet economy does not imply that the Soviet economy performs surprisingly well. On the contrary, the existence of allocative efficiency is a symptom of and may be caused by its stagnation in technological innovation.

(IV) The debate over allocative efficiency

And now we finally get to Murrell's article, one of the ones used in the quotes above to motivate the idea that the USSR was efficient, after all. Recall that Murrell is claiming that the USSR enjoyed both high allocative and technical efficiency.

First, Murrell clarifies that he does not dispute the empirical facts that the USSR underperformed. He only finds neoclassical explanations for this wanting,

The second half of the paper discusses empirical evidence, but of a particular sort. Much research shows that centrally planned economies perform less well than market economies; that fact is not in dispute. But few studies test whether the superiority of market economies appears within empirical models derived using the framework of basic neoclassical economics. Those studies are the relevant ones for the present exercise. I should emphasize that this paper addresses only the usefulness of neoclassical theory as the broad underpinning for reform, not the necessity of reform. Clearly, central planning has performed poorly. Real-world market economies, moreover, must contain many useful lessons for reforming economies. The issue addressed here is whether those lessons are best extracted using the filter of neoclassical theory. T h e central conclusion is that economists must look outside the standard models of competition, the focus on Pareto-efficient resource allocation, and the welfare theorems to build a theory of reform.

Murrell echoes again Danilin's study, contrasting the high level of technical efficiency found there (Or allocative, for Whitesell), with the one present in the West, and finding the Soviets superior in that respect, declares this to be unexplained by the literature, fully ignoring our reviewed papers above about the inverse relation between static and dynamic efficiency.

(Remember, this estimates are with respect to a best-practice enterprise in the same system and country)

He argues that even by absolute measures, there doesn't seem to be much difference between State-owned and private firms. But we must consider that a) The study was carried out in Poland, and b) This claim is backed by only that one study, Brada and King (1991). The study in question examines firms in the period 1960-74, and does say that

Our results indicate that on average the technical efficiency of state and private agriculture does not differ although the pattern of inefficiency is somewhat different. Thus, we conclude that the internal organization of socialized farm units does not make them inherently less technically efficient than private farms

But, first, just one study for the easiest to plan sector there is, agriculture, is not enough to support a broad claim about absolute technical efficiency.

And second, the paper does find negative conclusions overall,

distribution of inputs does lead to a sub-optimal allocation of resources in Polish agriculture. Thus, we agree with Johnson and others who argue that it is the environment of socialized agriculture rather than the socialized nature of farm units that leads to the poor performance of the agricultural sector in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union.

In the light of the rest of the literature, and other posts in my Soviet Series, just one study is not enough to assert that the Soviet Union or socialist systems more broadly did have a similar level of productivity or efficiency compared to the West.

The results regarding allocative efficiency that he collects are the same as mentioned above: that is was on par with the West. But even though Murrell cites Whitesell's 1990 paper, where the explanation for the discrepancy between static and dynamic efficiency is given, Murrell himself does not even mention this explanation.

One good summary of the paper is given by Murrell himself:

Nobody doubts the poor technological performance of the centrally planned economies. However, the causes of technological laggardness can be explained by many different theories, each having different conclusions for reform. On theoretical grounds, the neoclassical paradigm is hardly a strong candidate for providing such an explanation (Nelson, 1981). Moreover, in exactly the area in which the neoclassical approach seems most applicable-process changes the results are less than convincing. Therefore, one must look beyond the standard neoclassical model to explain the poor technological performance of centrally planned economies.

So this article is more of an argument about why the Soviet Union performed poorly, rather than about whether it did.

Next article in the literature is 'Allocational efficiency - Can it be so?' (Nove, 1991). Nove recaps what I have been saying here (high allocative and 'technical' efficiency due to slow technological progress), but says the picture is incomplete: perhaps there are sources of inefficiency that are not showing up in the measurements taken by Whitesell and others.

(a) The 'success indicators' of Soviet enterprises were the value of turnover, or tons, or ton-kilometres, or other 'gross' measures familiar to students of the subject for many decades. Profits and costs were not high on the list of priority objectives. There were numerous well documented instances when cost reduction, or economy of material inputs, were penalised, and so consistently avoided, because they would reduce gross-value, tonnage and so forth. This influences the behaviour of management in applying for inputs. Superior organs may alter the input applications, but there is no evidence to suggest that they had any serious interest in allocational efficiency, as distinct from input-output balance. This is surely a source of inefficient use of resources. (b) Partly as a result of the perverse system of incentives, the Soviet economy notoriously uses more energy, more metal, is more input-intensive in relation to final output than Western countries. This too surely implies allocative inefficiency. These resources, if redeployed, could yield more output (though we cannot calculate how much more, since they would have to be used in conjunction with other inputs which have alternative uses). (c) Many sources refer to the hoarding of labour, for reasons that should be familiar: to cope with uneven arrival of inputs (and so with shturmovshchina, the end-of-plan-period rush), and also to keep a reserve in case labour is mobilised for the harvest (as is happening even today). At the same time, labour is also a bottleneck in some sectors and areas. Here again, there would be an evident gain from redeployment, but how could that gain be measured? (d) Hoarding of materials, excessive inventories, are also notorious for reasons familiar. Surely an allocational inefficiency too? The practice of'self-supply', i.e. making one's own components, forgings, castings, foregoing the advantages of specialisation and of economies of scale, is equally well documented. While this could be seen as technological inefficiency, its cause is the same as the cause of hoarding of materials: uncertain and unreliable supply, i.e. (literally) allocational inefficiency. (e) Inputs 'frozen' in uncompleted construction (the well-known and amply documented dolgostroi, or nezavershenka) are surely misallocated? It is unnecesary to quote evidence that this is a major source of waste of resources; there is so much of it, published over the years. (f) What of the value of the inputs? How can one relate 'marginal rates of technical substitution' when there are no factor markets, and when neither Western analysts nor Soviet allocating officials know the real cost (including opportunity cost) of resources? (g) Can one ignore the quality (and so the use-value) of the output"! Can efficiency of allocation be totally separated from the use to which the allocated resources are put? One could fill several pages with evidence about the deplorably low quality of Soviet agricultural machinery, for instance. Many (including, very colourfully, Gaidar, cited below) describe much of it as 'rubbish'. Here it is important to stress that, in the absence of real markets and with weak user resistance, products of very indifferent quality can be foisted on customers at prices which have little connection with use-values. If one uses material resources and labour to produce goods of little value, should not this react (via feedback) on the value and allocational efficiency of the inputs? (h) Agriculture provides illustrations of other kinds of misallocation. Gaidar refers to 'vast, ineffective capital investment..., the erection of reinforced concrete palaces for low-productive livestock, the digging of [useless] irrigation canals, the supply of record quantities of painted scrap-iron proudly described as agricultural machinery...', and points out that in 1971-85 the agricultural sector obtained investment of 590 billion rubles, 'yet the national income in comparable prices created in this sector in the middle of the 1980s remained on the level of the early 1970s'. 2 The activities of Minvodkhoz, the ministry of water resources, in fulfilling plans in rubles by selecting the dearest drainage and irrigation work have been much criticised; quotations could fill several pages. Yet farms are unable to obtain much cheaper and most urgently needed and effective inputs. Allocational efficiency it surely is not.

[...]

Let us give the word 'inefficiency' the meaning attached to it by common sense and by the bulk of the Soviet economic profession. The neo-classical apparatus, as Wilhelm pointed out, 5 'assumes an economic universe in which prices and quantities are mutually interactive'. It is also a universe in which values and prices are related to user preference, one in which the market brings together costs of production and use-values. In such a context, it is possible to say that an alternative use of resources which results in a rise in net output or GNP is likely to represent a gain, a more efficient use of these resources. Soviet prices do not, either in theory or practice, have such characteristics. They are therefore a poor measure of efficiency, inefficiency or the effects of allocation or reallocation.

...

Will those who disagree with this judgment please expound their arguments.

That is: How can the economy be allocatively afficient given the above, Nove asks? Isn't it more plausible that there are measurement errors?

Josef Brada (1992) replies one year after that ('Allocative efficiency - It isn't so).

Nevertheless, Nove's reply does not resolve the central methodological and intellectual issue, namely, if indeed the Soviet economy is inefficient, then why does Whitesell's review of the econometric and statistical evidence lead to the opposite conclusion. I argue here that it is not a matter of poor modelling or bad data, or simply that modern economic theory has no use in the study of the Soviet economy [Like Murell also says], as Nove seems to imply in his rebuttal (pp. 578-579). Rather, I argue that Whitesell has based his conclusions on faulty conceptualisations of economic efficiency, thus leading him to misinterpret what is relatively straightforward and legitimate information about the efficiency of the Soviet economy.

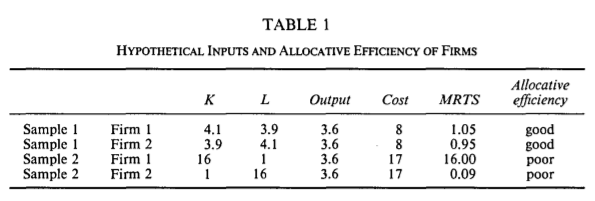

First, Brada criticises an inference Whitesell (and by extention Murrell) makes about Danilin's cotton study: the fact that cost differences between cotton producers are small does not imply that the marginal rates of substitution are equal, and if these are far from being equal, then there is allocative inefficiency. He then proves with a small example why that is so

If firms face the same prices, cost differences will be small if marginal rates of substitution between inputs are similar in different firms and if firms have similar levels of technical efficiency. (Whitesell)

Whitesell clearly means the proposition in the last sentence above to read that cost differences 'will be small if and only "marginal rates of substitution are similar in different firms...', since he deduces similar marginal rates of substitution across firms from evidence on the other points in his proposition, namely the same input prices for all firms and similar levels of technical efficiency. Unfortunately, this proposition is utterly false. There is no relationship between similar levels of technical efficiency and costs on the one hand and similar marginal rates of technical substitution among enterprises on the other.

Assuming Y=AK^0.5 L^0.5 where A=0.9, and that MRTs are calculated as K/L, it follows that firms with an unbalanced labour/capital ratio will produce at higher costs, and will have higher MRTs, even though their production function is exactly the same. In sample one, one can infer MRT around 1 from equality of prices, but that is not so in sample 2. Hence, we would also need to know the production functions, and the capital/labour allocations to say anything about allocative efficiency, contents Brada.

Another methodological complaint he makes is that Whitesell is inferring that Soviet trade is efficient from the fact that

export goods have low domestic opportunity costs of production compared to world prices, and imported goods have relatively high domestic opportunity costs

Yet that's a condition to profit from trade, not for trade fo be efficient. What we would need for that is to observe patterns of trade that tend to equalise costs and prices between the country and the world. This studies, as of 1992 have not been done, and given the dodginess of Soviet prices, they seem difficult to do anyway.

(The other complaint regards Barreto and Whitesell (1992), which I omit, as you already get an idea)

After Brada dropped his academic mic, no one else has cited this paper, and naïve inferences are still made from these econometric studies.

One final study in this section is Escoe (1996), studying individual republics and industrial branches rather than aggregating at the national level, who finds high technical efficiency (firms producing near their PPF), but low allocative efficiency (gains can be made from reallocating inputs),

It is not surprising to find evidence of greater technical efficiency than allocative efficiency in Soviet industry. Firms generally attempted to maximize output, given relatively stagnant production conditions (technology) and centrally allocated inputs. Output remained the key economic criteria throughout Soviet history. Thus, we would expect to find most firms operating near or on their given PPF (technical efficiency).

However, the individual enterprises had a limited ability to control their inputs which were allotted in a way that reflected planners' objectives (many of which were non-economic) and incomplete or flawed information (as ministry officials had less information regarding the production conditions of individual enterprises than did the enterprise directors). Furthermore, the firm's management faced incentives that encouraged the hoarding of resources (especially labor) and that did not place a high priority on cost minimization. These later factors likely led to low levels of allocative efficiency.

Thus, the answer to the question: "Was Soviet industry efficient?" is both yes and no. On one hand, the USSR, by virtue of bureaucratic competition, plan directives, and stagnant technologies, achieved rather high levels of technical efficiency. On the other, resource hoarding, poor information, and poor incentives resulted in increasing allocative inefficiency.

There are not many responses to this paper, so we can take the conclusion to be sort of settled: Soviet enterprises were producing near their PPFs, there were some gains to be made from reallocating factors, and this was to be expected given lower rates of technological change.

One final note regarding claims of technical efficiency: saying that technical efficiency within an industry is high does not mean that the industry is absolutely productive (See Kornai's figures for actual production). It is like saying that, controlling for latitude, a given location in the Sahara desert is not particularly hot. And surely that can be true, but it would be ridiculous to then infer that such a spot is a nice place to live.

(V) The Easterly Saga

Another stream of papers begin with The Soviet Economic Decline (Easterly & Fischer, 1995). This paper is not exactly about productivity, but about the broader question of the cause of the decline,

Why did the per capita economic growth of the former U.S.S.R. decline and then stop, contributing to the final collapse of the Soviet economic and political system? Accounts of the declining Soviet economic growth emphasize different causes: the Soviet reliance on extensive growth, which, given the slow growth of the labor force and the falling marginal productivity of capital, eventually ran out of payoff; the declining rate of productivity growth or technical progress associated with the difficulties of adopting and adapting to the sophisticated technologies being introduced in market economies; the defense burden; and a variety of special factors relating to the absence of appropriate incentives in the Soviet system, including corruption and demoralization (Banerjee and Spagat 1991; Bergson 1987b; Desai 1987; Ofer 1987; and Weitzman 1970). In this article, we examine alternative explanations with special care to place the Soviet growth performance in an international context.

The paper first analyses growth (something I also did here, updated with their conclusions), and find it wanting once usual suspects (initial GDP, population growth, investment ratio to GDP, etc) are controlled for. That is: The Soviet System reduced growth, given all of these factors.

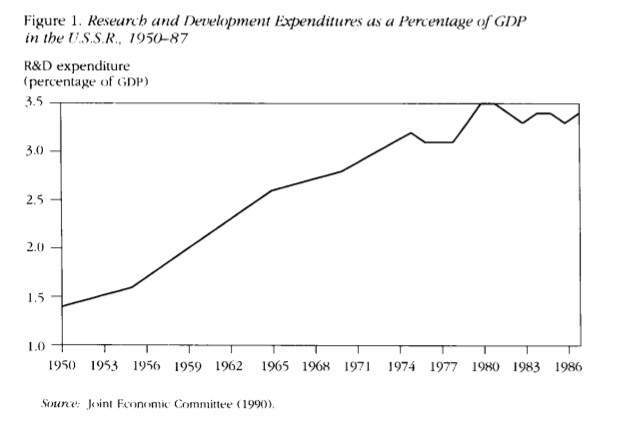

Then, they analyse causes for decline, considering and rejecting first disincentives for innovation, and a high defense burden (They say this was a very minor cause, if anything). Easterly does agree that the Soviet system generates disincentives for innovation, but that these did not got worse over the years, and so this could not have caused the decline, unless we get picky and argue that perhaps it was the sectoral composition of R&D within the civilian sector that wasn't being allocated properly.

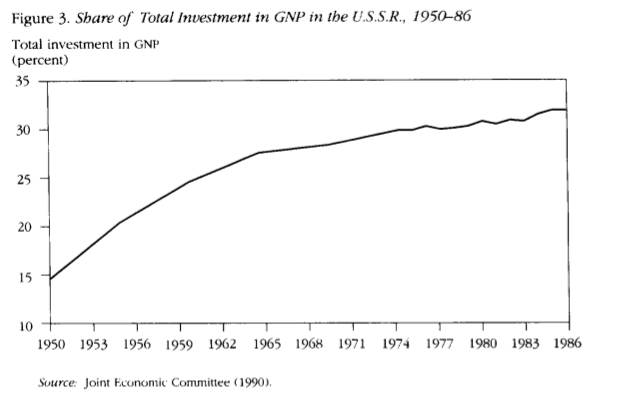

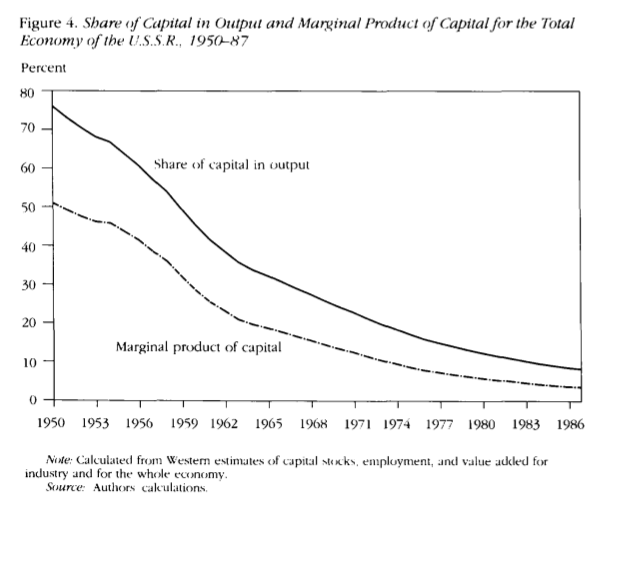

They then study the extensive growth hypothesis: Was Soviet growth mostly driven by input accumulation, rather than productivity improvements? Seemingly: Capital-output ratios were increasing throught most of USSR history (while they tend to be constant in capitalist countries). This means that more and more capital was required to produce additional units of economic goods. Another prediction of the hypothesis is that the share of GDP devoted to investment will also increase, and that is also seen in the data,

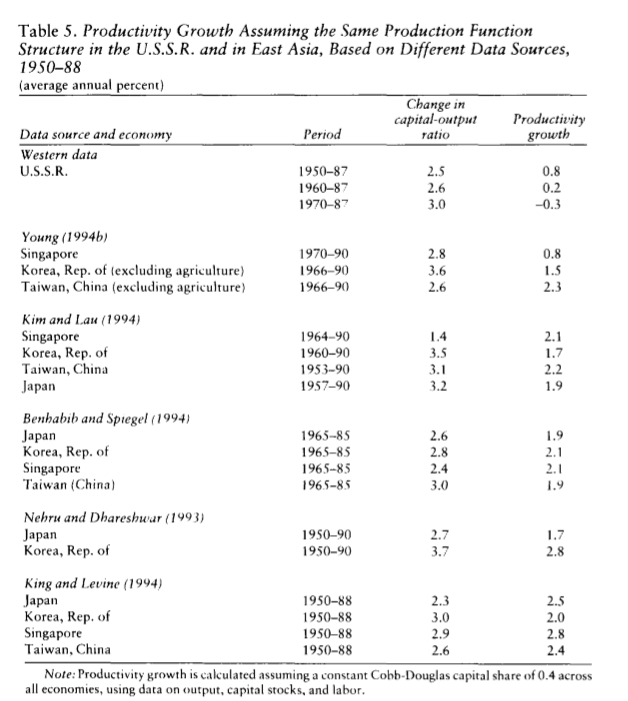

These patterns of growth can also be seen in the East Asian economies of decades ago. So why did Soviet growth decline and EA's didn't?

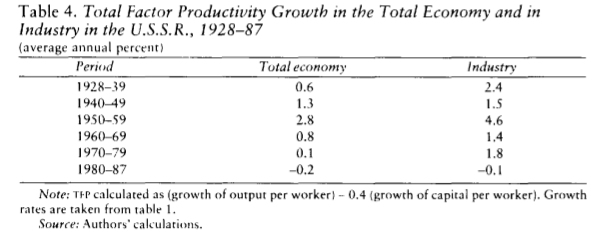

Easterly and Fischer turn to TFP, and finds differences in the rate of growth of TFP:

They further compare this with the average rate of TFP growth for all economies (1960-90), and find the USSR to be one percentage point below where it should.

Easterly finds this decline in TFP puzzling, as R&D expenditures were increasing. Here I think he makes the mistake of equating TFP with technological progress, So to get the results he wants ( :-) ), he uses a CES production function rather than a Cobb-Douglas. From previous work, it is found that CES fits the data better if a low rate of substitution is used. (Remember that Whitesell had found a rate of substitution around one [2] ; Easterly uses 0.4).

But if one does that, then one gets a different explanation for the decline: It was declining marginal returns to capital, not a slowdown in TFP, what caused the decrease in the rate of growth. His revised estimate for TFP, then, is a rate of growth of 1% per year, and it was constant, not declining.

He then surveys other ex-socialist countries, and also finds low rates of substitution there, and much higher rates in East Asian economies, which explain the puzzle of why their massive capital investment did not enter into decreasing returns as fast as the Soviet's.

In a final section, he explains why he was getting higher rates of TFP growth, it comes down to a slight 'misuse' of the Cobb-Douglas production function. The conclusion would have been valid if the elasticity of substitution were unity. But since he argues that it wasn't, then getting TFP from Cobb Douglas will result in an underestimation. [3].

Our results with the U.S.S.R. in the international cross-sectional growth and productivity regressions suggest that the planned economic system itself was disastrous for long-run economic growth in the U.S.S.R. Although this point may now seem obvious, it was not so apparent in the halcyon days of the 1950s, when the Soviet example was often cited as support for the neoclassical model's prediction that distortions do not have steady-state growth effects. Economic systems with low substitutability may deceptively generate rapid growth with high investment, only to stagnate after some time. Because a heavy degree of planning and government intervention still exist in many developing economies, the eventual fate of the Soviet economic system continues to be of interest.

Now, Beare (2008, a couple of years after Easterly's paper!) appears in scene. Recall that this paper was used by one of the blogs at the beginning of the post to argue that Easterly was wrong and that substitution elasticity were higher, as argued by Whitesell some years before Easterly. If you are wondering what is Easterly's reply to Whitesell's findings... there isn't any. His papers are not referenced in Easterly's work.

Okay, so what Beare essentially says that Easterly-Fischer made a mistake in the formulation of their regression analysis. When corrected, the coefficients identified by Easterly increase so much in their dispersion that they cannot be used to support anything. Beare applies his corrected analysis to a CIA, Khanin, and his own dataset's.

The results we have reported in the CIA, KHA and OFF columns of Table 1 and Table 2 reveal very little about the nature of the Soviet economy during the sample period. There is evidence that the rate of technical change was declining over the sample period, but we can say almost nothing about the elasticity of substitution or capital share parameters. The standard errors, and the discrepancies between data sets, are simply too large. This should not be surprising. Even if we ignore the poor quality of available data, estimation of a nonlinear model such as (2) using only thirty-eight observations, with a trend term that changes slope every ten periods, would seem to be extremely ambitious.

The apparent support provided to the extensive growth hypothesis by the results reported by Easterly and Fischer is clearly nothing more than an artifact of their inappropriate trend specification. What is surprising is that the defect in Easterly and Fischer’s analysis has not been noted previously. It has been more than a decade since the paper in question appeared in the World Bank Economic Review. As of January 2008, a search of the Social Sciences Citation Index yields 41 citations of the paper (including the working paper versions). None of those 41 papers note the error. Many refer specifically to Easterly and Fischer’s claim that the elasticity of substitution between capital and labor in the Soviet economy was significantly below one.

What Beare seems to suggest is that we cannot say much about the elasticity of substitution, but we can see that TFP growth was decreaseing.

Easterly replied in the same journal issue, and agrees with Beare,

W e are grateful to B eare (2008) for the valuable service of re - checking our old results (Easterly and Fischer 1995). Beare’s main point is correct: we made a careless error in constraining the intercept of the time trend to be constant while allowing trend coefficients to vary across decades. The consequence of this constant intercept assumption was not that our estimated equation produced crazy jumps at the end of each decade, as Beare’s Figure 1 might be taken to imply. It was instead that we biased the trend coefficients to be equal across decades (as Beare recognizes soon after Figure 1). So we gave biased support to our story that the slowdown in Soviet growth was not because of slowing TFP growth but rather was because of the extensive growth strategy of reliance on capital accumulation with a sharply falling rate of return to capital caused by a very low elasticity of substitution between capital and labor.

They admit doing a proper estimation with the data they have is difficult, but nonetheless they try, imposing that the influence of TFP on growth is quadratic (e.g. Y=f(T,T^2,K,gamma,alpha) where alpha is the capital share and gamma is the elasticity of substitution. They find a capital share of 0.83, and an elasticiy of substitution of 0.49. They admit then that TFP did fall over the period, but their estimate of the elasticity is low enough to support their story about the decline.

The final paper that we will discuss in this line of research is Nakamura (2015), who returns to the extensive growth hypothesis using again CES functions, and newer statistical methods. His results confirm what we just saw: Both low elasticity of substitution (0.25), and a decreasing trend of productivity growth. However, again like we just saw, the uncertainty present in the estimates for the elasticity is too high, so it doesn't provide definitive support to Easterly's hypothesis. The author agrees with Easterly's correction that it was both TFP and declining returns to capital what caused the Soviet decline.

(VI) Conclusion

So in the end, I think we can conclude that the Soviet economy was technically efficient in the trivial sense that soviet enterprises were working in the PPFs, given their level of technological development. This was in turn caused by slow and slowing technological progress. Allocative efficiency was low, as Novesays, due to the planning process itself, and TFP growth was lower than in the West, and decreasing. Finally, the growth model pursued by the Soviets, accumulating capital to generate more capital, proved to be a recipe for a quick takeoff, but also for stagnation and decline. To be sure, it didn't by itself cause the collapse of the Soviet Union, but it did contribute to the factors that led to it.

The analysis here could be made richer by a microanalysis of individual technologies and their use and difussion, and about the lives of the managers, scientists, engineers, and workers, that worked in the Soviet system, to understand better the root cause of these stylised macroeconomic facts here analysed, but that would fill another post.

Bibliography

Balassa, B. (1964). The Dynamic Efficiency of the Soviet Economy. The American Economic Review, 54(3), 490-505.

Barreto, H., & Whitesell, R. S. (1992). Estimation of output loss from allocative inefficiency: A comparison of the Soviet Union and the US. Economics of Planning, 25(3), 219-236.

Beare, B. K. (2008). The soviet economic decline revisited. Econ Journal Watch, 5(2), 135-144.

Brada, J. C. (1992). Allocative efficiency—It isn't so. Europe‐Asia Studies, 44(2), 343-347.

Danilin, V. I., Materov, I. S., & Rosefielde, S. (1985). Measuring enterprise efficiency in the Soviet Union: A stochastic frontier analysis. Economica, 52(206), 225-233.

Desai, P., & Martin, R. (1983). Efficiency loss from resource misallocation in Soviet industry. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 441-456.

Easterly, W., & Fischer, S. (1995). The Soviet economic decline. The World Bank Economic Review, 9(3), 341-371.

Easterly, W., & Fisher, S. (2008). A reply to: Brendan K. Beare. The soviet economic decline revisited. Econ Journal Watch, 9(2), 135-144.

Escoe, G. M. (1996). The efficiency of Soviet industry. Comparative Economic Studies, 38(2-3), 71-86.

Murrell, P. (1991). Can neoclassical economics underpin the reform of centrally planned economies?. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(4), 59-76.

Nakamura, Y. (2015). Productivity versus elasticity: a normalized constant elasticity of substitution production function applied to historical Soviet data. Applied Economics, 47(53), 5805-5823.

Nove, A. (1991). ‘Allocational efficiency’—Can it be so?. Europe‐Asia Studies, 43(3), 575-579.

Weill, L. (2008). On the inefficiency of European socialist economies. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 29(2), 79-89.

Whitesell, R. S. (1985). The influence of central planning on the economic slowdown in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe: a comparative production function analysis. Economica, 52(206), 235-244.

Whitesell, R. S. (1990). Why does the Soviet economy appear to be allocatively efficient?. Europe‐Asia Studies, 42(2), 259-268.

[1] Yes, there are TFP values in that article, but we also have values from more recent papers, which argueably we should consider as more reliable. Data quality should stay constant or improve with time, prima facie.

[2] More recent work studies other socialist economies. Here I have mostly focused on the Soviet Union. The most recent paper is Weill (2007), and finds that they are less than half as technically efficient as developed countries.

[3] Output elasticity is the relation between a change in output and a change in an input. An output elasticity of one for factor K means that an increase of one unit of capital leads to an increase of one unit of output. So if you want to grow by throwing resources at capital goods, the amount of capital will be growing much faster than the economy, hence the decreasing marginal productivity of capital, and the necessity to invest more and more to keep growth up.

Remember this figure is the share of capital in output: how much of output is 'rewarded' to capital, not how much is invested. In the end all of the output was collected and allocated by the State.

[4] For an analogous reasoning about why TFP!=Technology, see here. Note that there a Cobb-Douglas production function is used, while Easterly uses a CES function.

Comments from WordPress

- The Soviet Series: From farm to factory. Stalin’s Industrial Revolution | Nintil 2017-02-04T19:38:13Z

[…] and growth by increasing inputs (capital and labour) alone is not sustainable without accompanying increases in productivity. The cold war could have been a, but not the, factor explaining that decrease in […]

Ian Wang 2016-11-08T04:31:14Z

Thank you for a very interesting post.

I spent 2 years in the USSR during its decline and breakup (1989 – 1991), and I have a few personal, anecdotal observations. As a chemist / medical researcher, I’m well aware that the plural of anecdote is not data. On the other hand, anecdote is useful for framing and generating hypotheses, and my first-hand observations lead me to think that some of the assumptions in the models you outlined miss the mark or prematurely dismiss factors as irrelevant.

I’d like to start with the idea that the military expenditures did not have a significant impact on the economy or on efficiencies. Everything produced in the USSR above the level of simple consumer goods was made with a secondary military purpose in mind, from tractors to commercial airliners.

In the latter, seats were damn uncomfortable because they were made to specifications that required that the plane be rapidly convertible to a military transport aircraft (i.e. the seats were bolted onto metal frames that were quickly removable), decreasing economic utility from a Western point of view. While that particular example would not make for significant productivity differences, the same principle applied to the former meant that heavier gauge steel in the body and more robust but less fuel efficient engines were employed, making the heavier, slower tractors much less efficient at their primary purpose in order to maintain utility in a military role they were never called to serve.

This was even more pronounced in the post-war years, when even small passenger automobiles were manufactured with military service in mind. (That gradually eased by the 1970s). One of the original Ladas in the 50s was nicknamed the “Jewish Armored Car” with typical Russian anti-Semitism, because its body was made with low-grade armored plate. One friend pointed out a place in a village I visited where his grandfather’s “armored car” fell through a wooden bridge. Unnecessary resource utilization such as this (in gas, unneeded steel demand, and road repairs) is not really captured in the assumption that defense was not a significant source of resource utilization, because the costs were borne in the civilian sector.

Next, I think that another aspect of the inefficient Soviet economy not mentioned in the papers that you just described is low quality. On my very first day in the USSR I was struck by the massive place in the economy for repair services. What really struck me were the enormous numbers of stores bearing the sign Ремонт Часов – Watch Repair. It seemed like there was one on every block.

Now it is true that Soviet allocation of production and the corresponding scarcity of consumer goods caused people to take care of the things they had and repair rather than replace items more often than in the West (I think this ties closely with the idea of high technical efficiency in factories that you wrote about above), but the number of repair facilities immediately indicated to me that the quality of goods was such that repairs were needed quite often. My experience over the next couple of years bore out the correctness of this assumption. My friends used to joke that “Russian watches are the fastest in the world”.

In the laboratory where I worked, higher quality Czek or East German equipment was the most prized, and even in durable consumer goods (washing machines, TVs, ovens) this was true. Simply counting output does not give an idea of efficient resource utilization if useful lifetimes are not considered. My apologies if this aspect of production is considered in the original articles, I just did not see any evidence of this in your synopses of the arguments, and I think it’s a significant piece of the economic puzzle when considering why the USSR declined as rapidly as it did. The Kalashnikov is a remarkably durable tool, but anything much more complicated than its recoil and auto-feed mechanism seemed to be beyond the capabilities of Soviet QC engineers.

Another major factor in the economic decline of the USSR was not production, but distribution. The supply-side analyses you cited don’t seem to take this into account as a measure of efficiency, either. I realize that’s not the aim of those papers, but their conclusion sections seem to puzzle about models of efficiency, and without characterizing a distribution system that could only charitably be described as rising to the level of “shitty”, those musings miss much of the story.

Even before the late USSR period, shortages were common. Some of this was due to poor central planning – I worked construction in the summer of 1989 with the MSO (Moscow Student Workers Brigades) – and the Russians were immensely relieved that we had brought our own boots, because Gosplan had screwed up that year and left the entire country with a shortage. However, poor planning should show up in the form of lower production numbers in the articles you cited.

What probably did not show up, however, was inefficiencies with distribution of the goods that were made. This was due to two main reasons, and neither of those seem to show up in the analyses you mentioned. The first was diversion. In goods that Gosplan had shortchanged, the mafia and / or Communist officials (often one and the same in the countryside) diverted and then sold goods for higher than state prices. When goods did appear in the state stores, lines were enormous – I remember seeing a line that stretched for 4 blocks in Leningrad in late 1989. Having become acculturated to the country, I jumped in line before even knowing what was for sale. It turned out to be razor blades.

While you can argue that the goods in this case got to the consumers eventually, this is on a personal level an inefficiency akin to the input irregularity that led to hoarding of inputs in factories. People hoarded these basic necessities, which led to even greater shortages. Since the wife bore an inordinate shopping burden, it was accepted custom to let women skip out on work early to find scarce goods, leading to both increased sexism and decreased personal productivity. It also led to the impression of a failing system (which has a lot to do with the reason the USSR fell so suddenly) when the Western economists were telling us “but the Russians are still making stuff”. You could not have guessed at production levels based on our empty shelves, though.

The second aspect of diversion was the drain of the black market. While working as laboratory assistant at Kaunas Technical University in 1990 / 91, I had a ration card. Prices in Lithuania were still controlled by the state, but in neighboring Poland and Byelorussia, free market of varying degrees reigned, and the mafia were making significant profits based on the price differentials, causing shortages. This was true for many other types of goods where the Soviet quality was good enough to compete at the lower end of the Western and newly free Eastern European markets.

Within the domestic black market, the shadow economy also had direct impact on productivity of state enterprises, which is likely not reflected in official statistics. For example, when I was working construction, the (mostly alcoholic) regular crew we students were supplementing due to failure to meet quota were selling off our raw materials out of the back of the site. Since no Soviet version of Home Depot existed, if you were building a small “Krushchev Dacha” on your small parcel of allotted land in your kolkhoz, the only way to get building materials was to buy stolen goods from the factories or from construction sites like mine. So true productivity of, for example, brick production in some of the figures economists use is probably 1) downplayed due to reported “losses” or 2) mis-allocated to major projects like mine, when in fact it would up in some local Party Chief’s summer home.

All this is a long-winded way of saying that when I see supply-side productivity analyses such as the ones you critiqued in this post, my first retort is “yes, but did those goods reach the markets for which they were intended”?

Akin to the problem of diversion was that the inefficiencies in the transportation system were enormous. In the summer of 1990 I worked with the MSO again on a Kolkhoz needed extra hands in the harvest. I witnessed my friends cursing at unrefrigerated boxcars full of rotting cabbages that should have been in Moscow markets, sitting unattended on a siding because of poor rail traffic control. Those cabbages probably would have been counted in the CIA’s numbers as “produced”, but were never consumed. Without matching production with consumption, especially in the agricultural sector, most of these post-hoc economic analyses of the USSR have a significant data quality impairment.

If you want to know why the economy of the USSR collapsed, you have to ask yourself why the stores were so empty if the factories were still producing goods, even inefficiently. While resource hoarding within factories (this certainly went on) is acknowledged in the articles you cited, they don’t seem to give enough credit for post-production hoarding and re-sale that drove the perception of economic collapse among the rank and file citizens of the late USSR.

My final observation is that I hope that some attempt in these analyses is made to account for outright data fabrication. I witnessed a fair amount of that first hand, as well.

Sorry for the long post, but I thought that at least a few of the points I raised might be useful for you in framing critiques of some of these analyses.

Artir 2016-11-09T18:35:34Z

Thank you for your thoughtful and lengthy comment. I agree with you in what you say. In this post, I focused on a very narrow area of the Soviet system, and chose not to give a broader assessment. This post, if read alone, would make it seem like my overall idea of the USSR is more positive than it actually is, because I say that in some very specific sense, their factories were efficient, but the whole point of that was to show that one can still have that trivial efficiency, and a poorly performing system at the same time.

> Regarding military expenditures, I wrote a quick post about that here https://artir.wordpress.com/2016/05/31/the-soviet-union-military-spending/ I'm not saying that the defense burden didn't contribute to stagnation. I'm saying that it doesn't seem to be a cause of the collapse. Diversion of resources towards the military would have been a constant factor throughout the history of the USSR, and this would have caused slower, but not negative growth.

>Regarding distribution, etc, I agree with you. In other post of the Soviet series (I updated the post with a link at the top) I discuss other things. My series sort of assumes that the reader is familiar with a broad overview of the Soviet Union (the queues, inefficiencies, etc), and here I try to see how does actual research deviate from that. I should write an introductory post to sets things clear. Perhaps telling the reader to read Red Plenty is another thing I could do.

>Regarding data fabrication. Yes, I and the authors cited are well aware of the creativity the Soviets had when reporting economic figures, and accordingly they corrected for fabrications and mismeasurements. The more recent the papers, the more accurate the data, and we know that post 1985 or so, the data the Soviets were releasing was mostly the data they themselves were working with for planning purposes. The worst came around the Stalin years, where data manipulation was substantial and not consistent across time, making difficult to rely on data from that period.

- The Soviet Union series | Nintil 2016-11-07T21:52:11Z

[…] The Soviet Union: Productive efficiency […]

- The Soviet Union: GDP growth | Nintil 2017-01-27T09:31:18Z

[…] long-term run strategy. At some point you run out of people to put to work. I refer to you to this other post of mine for more info on […]

- ¿Fue la Revolución Rusa un éxito económico? – Juan Ramón rallo | elcato.org – Verdades Ofenden 2017-11-29T21:45:51Z

[…] estalinismo fue un modo ineficiente, represivo, parasitario y criminal de industrializar la URSS. Un modelo que no solo debe ser […]

- ¿Fue la Revolución rusa un éxito económico? - Economía y Libertad 2017-12-10T15:21:59Z

[…] estalinismo fue un modo ineficiente, represivo, parasitario y criminal de industrializar la URSS. Un modelo que no solo debe ser […]

- ¿Fue la Revolución rusa un éxito económico? (II). – juan Ramon Rallo / Blogs de Laissez faire – Verdades Ofenden 2017-12-19T15:12:28Z

[…] estalinismo fue un modo ineficiente, represivo, parasitario y criminal de industrializar la URSS. Un modelo que no solo debe ser […]

Citation

In academic work, please cite this essay as:

Ricón, José Luis, “The Soviet Union: Productive Efficiency”, Nintil (2016-11-07), available at https://nintil.com/the-soviet-union-productive-efficiency/.

Comments