The Soviet Union: poverty and inequality

[This is part of the Soviet series]

The USSR Constitution of 1977 said

Article 19. The social basis of the USSR is the unbreakable alliance of the workers, peasants, and intelligentsia.

The state helps enhance the social homogeneity of society, namely the elimination of class differences and of the essential distinctions between town and country and between mental and physical labour, and the all-round development and drawing together of all the nations and nationalities of the USSR.

One would thus expect the Soviet Union to be a relatively equal society, and furthermore given the rights to all basic needs, one would expect little amounts of poverty. Alas, it wasn't quite like that.

A possible defence of the Soviet Union is to appeal to equality and basic needs. Even if one has accepted that the system was worse performing than the market economies of the West, one could still argue that what really matters is to cover basic needs first. What use, could one say, is having an economy that allows the existence of super-rich people and supermarkets that sell five different kinds of hummus when there are other people that are destitute?

Our analysis begins with an article published in 1977 by Alastair McAuley, The Distribution of Earnings and Incomes in the Soviet Union. The reason being no other that this article is one of the first ones. The data he uses in his article comes from official Soviet sources, with a peculiar catch: the government itself doesn't publish the income distribution statistics directly, but they do publish several data items that can be used to put it together. McAuley discusses the advantages and weaknesses of these datasets (Family budget surveys, income surveys, earnings censuses, and earnings surveys). Some findings of his were that inequality (Measured by the decile ratio) decreased by around 40% in the 1956-65 period, achieved by a faster increase of the earnings of the poor (144%) compared to those of the richer citizens (38%). The authors point out, though, that if looked from the point of view of how many more rubles they are making, the gains in absolute terms are equal for all groups. By 1967-68, the decile ratio was around 3, meaning that the richest citizens, on average, were earning three times as much as the poorest ones, which seems quite equal. In comparison, the UK had a ratio of 3.4.

The article also provides an estimate of how many families were in a situation of poverty, as defined by the fact that in 1974 the government introduced a subsidy for needy families that earned under 50 rubles per month. This, together with the fact that inflation rates are low, allows McAuley to retroactively calculate poverty rates in 1967, for he has data for that year. And that amount is staggering: In the best estimate, including state farm workers, around 40% of the entire population in 1967 would be considered as poor by the Soviet standards of 1974.

McAuley does provide tables with his estimates, but what is of interest here for comparison purposes are summary statistics like the Gini index, and yours truly ~~is too lazy to manually calculate them ~~knows that those are available in later papers.

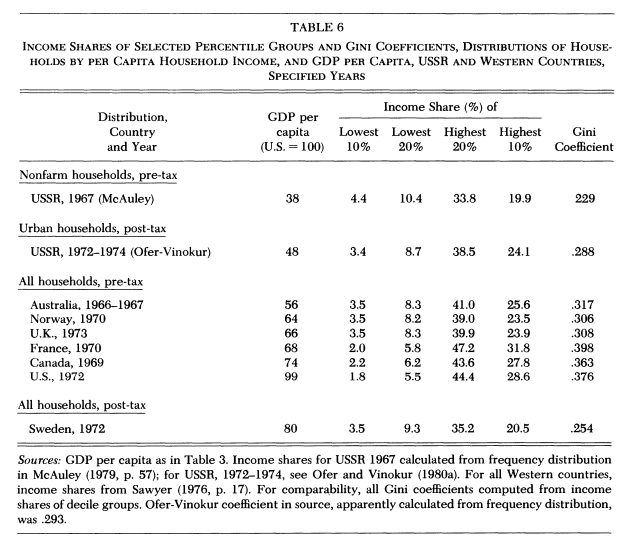

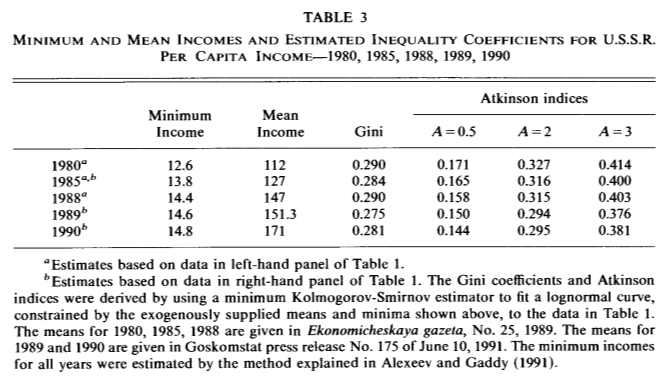

The next paper of relevance is the clearly named Income Inequality under Soviet socialism by Abram Bergson (1984). Like McAuley, he spends quite a few dozen pages discussing methodological issues and the tricks one has to go through in order to provide a reasonable estimate of the income distribution in the USSR. IN the paper he cites two Gini coefficients, using different data, methods, and different years. One is an estimate calculated from McCauley's data and the other from Ofer-Vinokur's papers that he references. According to Bergson, McAuley's data underestimates inequality, and Ofer-Vinokur overestate it, although he thinks the latter are closer to the underlying truth. Both numbers are not that different, as you can see in the table below. In any case, they reinforce the idea that the Soviet Union had indeed low inequality, comparable to Nordic social-democracies of its time.

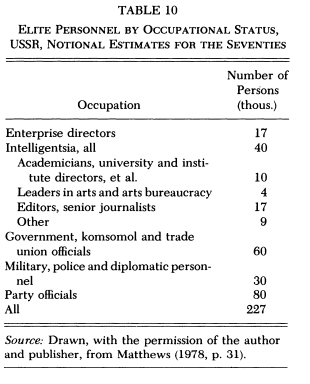

Section IX of Bergson's paper discusses the so called elite-classes of the USSR.

Who earns very high incomes in the USSR? How much do they earn? More may be known on these intriguing questions than might be supposed. If it is, that is due in no small part to Matthews' 1978 study supplementing sparse official releases with results of interviews that he conducted on Soviet "elite" groups. Those interviewed were almost all emigres from the USSR, and only a minor fraction were of elite status, as seen by Matthews, but the great majority had a "professional" background in the USSR, and could report on other's as well as their own experience.

Those elites are considered by Matthews (we'll get to his work later) as those who earn at least 400-500 rubles a month, 3.1-3.8 times average 1972 pay of all Soviet wage earners and salaried workers (WESW)* In the passing, he makes the interesting observation that 10% of WESW had earnings below the minimum wage of 60-70 rubles per month in the 1971-73 period.

How many elites were there, going by this definition? 0.2% of all employees. Matthews classifies someone into elite if they derive such an income from their main occupation. Bergson makes the observation that judging from the previously mentioned Ofer-Vinokur work, the number of elites would increase if instead of main job income one considers total income. Some also had a second job or a private job (as a dentist or retailer) This could raise the number of elites to 1% of WESW.

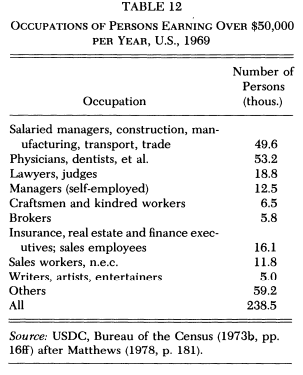

What occupations did they have? Bergson provides us with a table from Matthew's. For comparison, the distribution of occupations of high earners in the US is also shown:

In the same section, Bergson notes the fact that there is some degree of intergenerational transmission of eliteness.

The USSR allowed inheritance, subject to some taxation, but that wasn't a main source of intergenerational inequality. Rather, one would have to consider a bundle of status conditions (income, type of job, scientific publications, quality of housing, etc...) as for example Gregory Clark does to uncover a higher degree of intergenerational transmission of belonging to the elite.

And so, children of elite personnel, and high skilled workers such as engineers , who comprised around 14% of the population, accounted for 31.5-51% of enrolment in the universities for which data is available. Conversely, for manual workers and collective farmers, their children were substantially under-represented in the university population. The situation was similar in secondary schools. This situation was in spite of the Soviet State deliberately trying to equalise access to university:

The disproportionately low enrollment of children of manual workers in the universities represents a dramatic denouement to early post-Revolutionary efforts to assure their predominance. After a protracted period of preoccupation with merit under Stalin, measures to "rectify" the university social structure were initiated by his successors, but seemingly with only limited effect.

Also, children of those groups tended to be overrepresented in skilled occupations:

Something is known also about selected groups of specialists. Although reference is still not necessarily to elite personnel,it is illuminating that 62.9 percent of persons employed in "skilled mental work" or serving as "managerial personnel" in a Leningrad machinery factory in 1967 were children of specialists with higher education; 78.0 percent of the children of managerial personnel and 62.9 percent of the children of highly-skilled scientific technical personnel in Leningrad machinery enterprises in 1970 were either specialists or full-time students in advanced institutions; and 49.0 percent of "highly skilled personnel in . . . creative occupations" and 45.8 percent of personnel in "highly skilled scientific and technical work" in the city of Kazan in 1967 were children of employees in posts requiring specialized or higher education (Yanowich 1977, pp. 114ff; 0. I. Shkaratan 1973, p. 297).

Not very surprisingly, the children of the most elite personnel of all, the members of the Politburo, and also their spouses have tended to find "jobs which place them in the upper ranks of the intelligentsia, but not necessarily over the elite threshold.

While this persistence of status across time goes against the principles of socialism, its extent was lower than in the West, claims Bergson. But this, he warns, could potentially change with the decrease in growth that the USSR was experimenting at the time.

Regional inequality

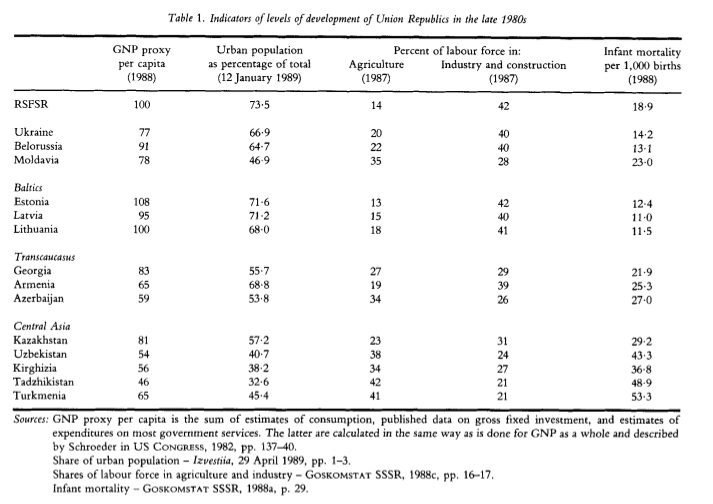

So far we have seen an overview of inequality in the aggregate of the USSR. But the USSR is mostly Russia and Ukraine in terms of population. How does the data look like if we look at the individual constituent republics?

The Soviet Union not only tried to equalise incomes across the USSR, but also in theory, also between different republics. Ozornoy (1992) mentions that indeed that happened until the 1950s, but since then, little convergence has happened. This is in spite of economic growth, as the birthrates in the poorer republics outpaced it, increasing the denominator of per capita GDP. Ozornoy mentions that for most of its history, investment policy in the USSR was essentially centralised, and it paid little regard to the differences between republics, considering only the USSR as a whole.

The pattern of investment distribution among the union republics during the period 1976-88 does not reveal any systematic effort to use the allocation of investment as a policy tool for reducing development disparities, particularly when allowance is made for the differing rates of population growth. Rather, the pattern suggests that the federal government, while providing an increment in investment to ensure some development in all republics, based its spatial investment allocation decisions on an assortment of general economic and geographical considerations, such as resource and energy development in Asiatic RSFSR, rates of return on capital, accessibility to markets and geopolitical factors. The primacy of the ‘state as a whole’ considerations over equity considerations in the investment shifts may be seen as a perfectly logical approach by decision-makers within the federal administration which actually pronounced that the task of inter-republican equalization had been resolved!

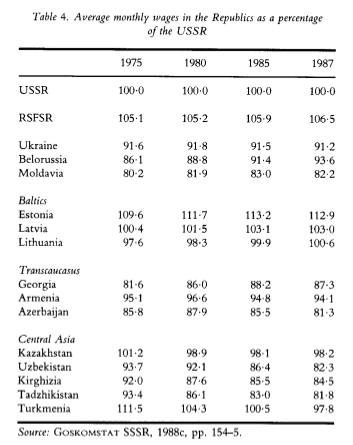

In the late 80s, this is how the UUSR looked liked decomposed by republics:

As you can see, this doesn't seem very equal, and to some extent it mirrors the economic development of the republics post-USSR. The richest republics were the Baltic's, and the Central Asian republics, the poorest. A view to salaries reveals the same picture, so our intuitive inference of average consumer income from per capita GDP is merited:

This issue was known and discussed during Gorbachov's late term, and serious sounding declarations were made at the time about the need to close the development gap between the republics,

With regard to reducing inter-republican economic disparities, Gorbachev initially suggested that budget allocations for social needs ought to be related to the efficiency of a region’s economy, i.e. to its contribution to the national economy. Neither his opening speech nor the Resolution adopted by the 19th Party Conference in June 1988 stated a reduction of regional economic disparities as a desirable goal. The escalation of national violence and the avalanche of national economic grievances, however, seems to have convinced Gorbachev that poor economic conditions could be underlying ethnic tensions.

For at the September (1989) CPSU plenum on nationality, he admitted: ‘Despite impressive progress in “evening out the differences”, serious problems still remain in this area’ (ibid.). He vaguely suggested the setting up some kind of mechanism for using state (federal) budget funds ‘to resolve consistently the pressing problems of those regions that are lagging behind’. The plenum’s resolution was formulated in ore specific language: ‘The country must have a system of economic levers and incentives which enables the USSR government, on the basis of theefficient use of state budget resources, to work in conjunction with the republics in pursuit of a purposeful line aimed at eliminating the lag in the economic development of individual regions due to objective factors and also to create an all-union fund to provide aid to regions affected by natural disasters and ecological catastrophes, and for the development of new territories’ (REZOLIUTSIIA, . . ., 1989)

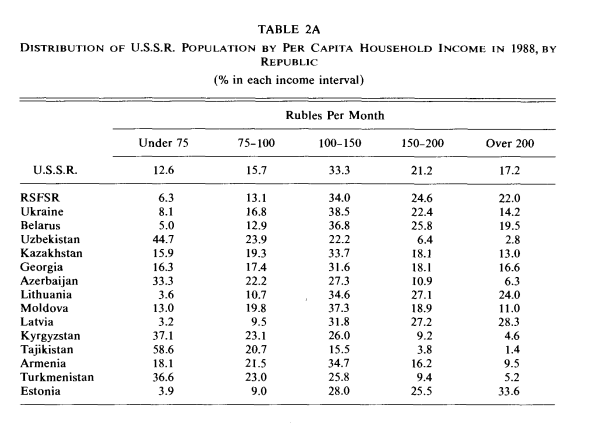

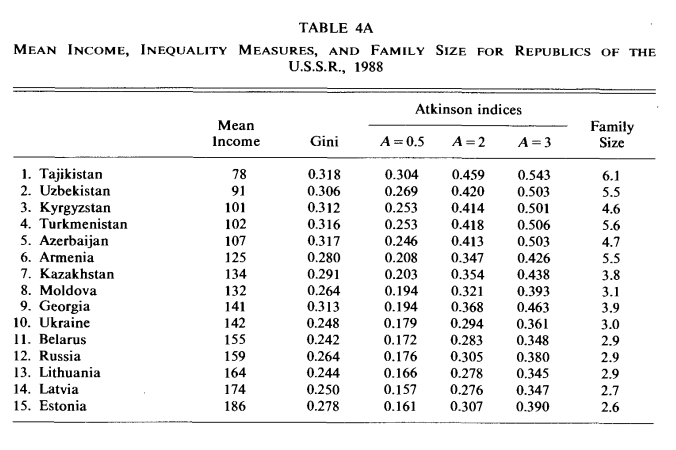

Detailed tabulated data for the 1980s can be found in Alexeev (1993), which I reproduce below:

EDIT (23/07/17):

Elite privilege

I forgot to add some key paragraphs from Bergson about some privileges that elites had. These were nonmonetary, and so they wouldn't appear in measures of inequality that rely on income like Gini. Matthews wrote a whole book about the elites in the USSR, but I haven't been able to access it online. Some of its contents can be glanced from here. It matches my priors about the USSR and, anecdotically, also the first hand experience that one of my uncles -from Romania- had during the Ceaușescu years.

I have been referring to the money incomes of elite personnel. Especially for such individuals, we must recall the limitations of money as a measure of real income (Section III). In view of the complex or privileges accruing to them, the residual influence of egalitarianism on the material status of elite personnel has surely become attenuated, if it exists at all. The complex of privileges itself calls for explanation. Why not simply pay higher money incomes to the persons in question, and allow them to procure in the market the corresponding material benefits? One can only conjecture that the higher money incomes would likely make the privileged status of the elite groups more conspicuous, and hence politically disturbing. In order that the monetization be meaningful, it would be necessary to operate the consumer's goods market more effectively. Under centralist planning, that might not be easy to do. The complex of privileges also has the advantage that it reminds the recipient constantly of his special status and of his dependence on the continuing favor of those who grant it.

Poverty

Most of what is known about poverty in the Soviet Union is gathered into a single book, the clearly titled Poverty in the Soviet Union, by Mervyn Matthews (1986). Here I concern myself with Part I of the book, that focuses directly on what it means to be poor in the USSR. Matthews, like the other authors, tries to put together his data from several sources, including not only scarce official reports, but also individual Soviet research papers, emigres surveys, and even _samizdat._Chapter 1 is dedicated to present the main sources, and explain what one can learn from them.

There we learn that in 1967, two Soviet economists, Sarkisyan and Kuznestova drafted basic budgets for a series of representative families. Their minimum budget pointed to a figure of 51.4 roubles per person for a family of two with two children. That is, 205.6 roubles per family. In 1965 the average wage was 87.8 roubles (175.7 for two earners), so he concludes that by their figures, more than half of the population would count as poor, which seems a weird albeit inescapable conclusion. They also designed a 'prospective minimum budget', representing what a poor family would be able to consume in a few years due to increases in production of consumer goods. That budget required earnings of 2x133.2 roubles, and this figure matched the average gross wage by 1976.

They also designed a 'rational' budget, costing 153.3 roubles per capita, putting it beyond the reach of the average family, as even by 1980, the average wage was 168.9 roubles. This was barely enough to sustain two people under the rational budget.

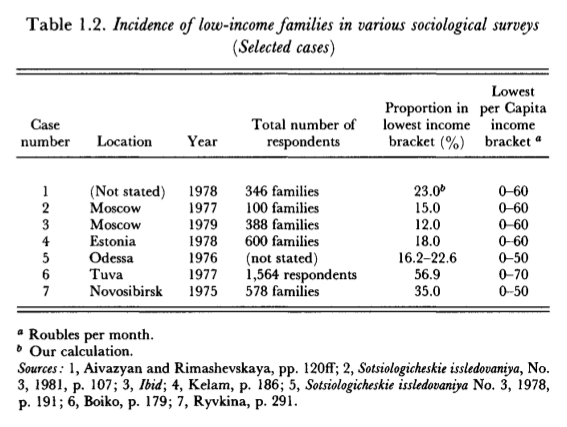

If we settle for a poverty threshold of 60 roubles in 1978 (A minimum budget for that year), then a sociological study carried out by Soviet economists finds that 23% of the population was poor (Sample size of 62000 family budgets, towns of origin not specified). In Moscow, couples were found to have a poverty rate of 12-15% (Sample size of 100-388 families in 1977 and 1979). In Estonia, one of the richest Republics, 18% of families with children were found to be poor. Other surveys show even greater rates in the Tuvan Autonomous Republic, populated by Tuvans, a Turkic people, and Novosibirsk.

Matthews also notes that the US poverty threshold, 32.8% of median income, a relative poverty measure, would put most of the Soviet population in the category of poor. This sounds as an unfair comparison: perhaps the poor in the USSR still enjoyed better conditions of living given that the State massively subsidised education, housing, healthcare, and pretty much everything else. This is dubius, given the other posts in my Soviet series, but we'll add some comments regarding this below. Some corrections would also have to be made for inflation (increasing poverty) and illegal job activity (decreasing it). Matthews attempts the exercise and comes up with revised figures for some cases, but the deviation is not substantial, although it slightly increases the number of people in poverty.

What did this poverty amount to, in practical terms?

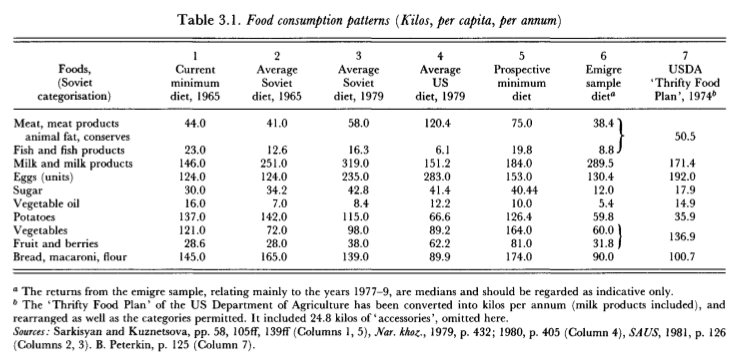

In terms of food, Sarkisian and Kuznestova calculated the food that the average family described above needed, you can see it in the first column:

Matthews does not fully believe that this reference diet was an average diet for the poor, as if you compare with column 3, the average diet for the whole USSR decades later was in many categories behind the minimum diet of 1965. In addition, scarcity of supply would have meant that not all of those items could have been purchased.

He claims that deriving the actual figures from official data is close to impossible. One way of getting it is asking emigres what they were actually eating (column 6), and this diet was behind the national averages for 1980 and the prospective minimum diet. Note that the emigre column is the median of the whole sample, not of the poorest, so at most this is an upper bound on what the actual poor were eating. Compare with column 7, based on a sample of what poor New York families had for diet. Both the emigre sample and the model budgets do point that Soviet consumption of fruit, vegetables, and meat was even below the average.

Underprovision of clothing is another aspect of poverty that Matthews discusses. Like with food, the model budgets allocate a certain amount of money to a certain amount of clothing. Clothing was quite expensive in the Soviet Union, and a winter coat, which seems like a basic thing to have if you happen to live in Russia, was extremely expensive, and could consume a whole month worth of salary or more for an average worker (120-200 roubles). A shirt was more reasonably priced, 8-12 roubles. But still, if one considers that such an amount supposes 10% of a wage, it is still extremely expensive. To put it into perspective, for the average monthly UK wage, around 1700 pounds after tax, it would mean an average shirt would cost about 170 pounds. Not surprisingly, 22% had no winter coat and 25% had no fur hat (in the emigre sample). 97% of the surveyed considered clothes to be a problem or an acute problem. And this is, remember, a sample of mainly Jewish emigres from an urban setting, not of poor people in particular. From this Matthews infers that the situation for the poor must have been worse.

Housing would seem to be a non-issue, as it was mentioned before, it was heavily subsidised. Housing was divided in houses provided by different public bodies (government, corporations...) and private housing (housing cooperatives and dachas). No one was allowed to have more than one house, except for dachas, but those were only legally usable in summer.

This system, while ruthlessly egalitarian on first sight, it actually wasn't:

A system such as this, oriented towards the provision of standard amounts of housing for all, with strict financial restraints, might be regarded as protective of poor people's interests. One might further imagine that the relationship between poverty and slum-dwelling, so characteristic of' capitalist' lands, would be weakened. This has not happened for several cogent reasons. Firstly, Soviet towns have always been characterised by acute housing shortages from which most people suffer.

Secondly, the provision of superior accommodation has long been used as a reward for service to the state, or as an incentive to work harder. The sharp fall in the per capita provision of urban housing during the first Five Year Plans, for example, necessitated special provision for managers and outstanding workers. The destruction wrought by the Second World War, and the neglect of the sector in the post-war decade, had the same effect. The Khrushchev leadership endeavoured to increase housing stocks, but it still had to urbanise rapidly in the interests of economic growth, and most housing privileges were retained. When the rate of urbanisation began to slow in the mid-sixties, the housing sector, though lacking the variety found in capitalist society, was still characterised by a good deal of differentiation. The Brezhnev leadership adopted a highly protective attitude to most forms of privilege, and maintained the existing accommodation benefits.

Thirdly, the allocation system has over time developed subtle informal mechanisms which work to the detriment of the less privileged citizens. The poor, for instance, have fewer chances of acquiring the better-quality accommodation erected by powerful organisations or enterprises, and are more likely to end up in meaner flats belonging to local Soviets. Poor people cannot usually buy living space in cooperative housing projects because, compared with the nominal rents in the state sector, such housing is extremely expensive. If they do so, the space they acquire is (to judge from our sample returns) close to the minimum, and mortgage repayments greatly exacerbate their financial difficulties. The poor have less of the political influence needed to speed progress through the local waiting lists (see Chapter Six).

The problem of Soviet slums has, of course, always been veiled in secrecy. The term, like 'poverty' still cannot be officially ascribed to any Soviet dwelling. But such dwellings continue to exist and are likely to house the poorest members of society.

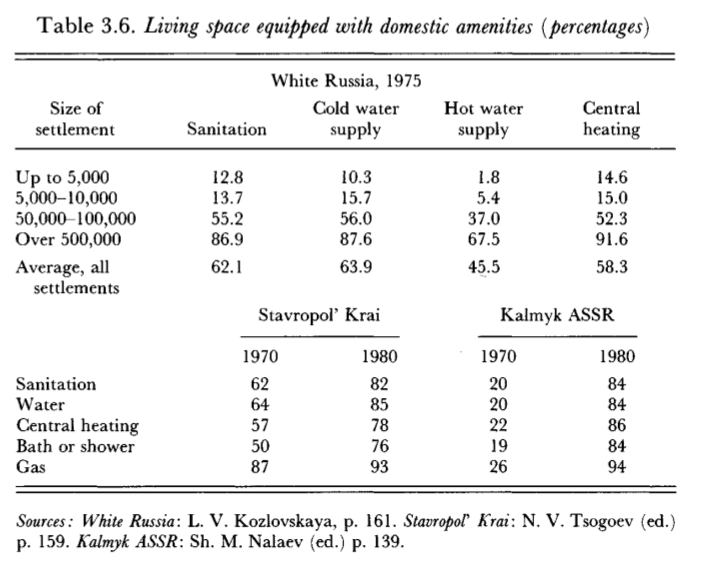

An in addition to that, some flats were communal flats (19% of the families from the emigre sample were in this situation). Unsurprisingly, 60% of the respondants in the sample thought that their space was rather inadequate or grossly inadequate. Basic equipment like sanitation or water supply improved throughout the decades, but didn't fully reach everyone by 1975, especially in smaller towns. While in larger settlements in Russia (1975) 87.6% of housing had cold tap water, only 10.3% of smaller settlements enjoyed this. For the masses of poor peasants and workers in smaller towns, this would have been even worse.

The budgets are an endless source of details, and so they also contain guidelines for what a minimum supply of household durables was, down to the number of chair (eight), cupboards (three), and kitchen stools (four). But Matthews again says that it is implausible that the poorest would have afforded this minimum budget. The cost of the furniture was around 1000 roubles, and that of 'cultural goods' (TV, radio, television, refrigeration, bicycle, camera, watches, and sport items) was around 400 roubles (In 1979). Eight years worth of payments would have been required to acquire all of this, assuming that nothing breaks or deteriorates. Obtaining loans was extremely hard, and the State Bank did not offer them to individuals, so acquiring all of these elements would have been even harder than initially thought. One could make the critique that a person lacking eight chairs and a television is not poor, that we should look only at food, water, housing and other core essentials, but the point wouldn't be much changed, as even these basics did not fully reach everyone.

And finally, it is worth having a look at what were the poorer and richer citizens of the USSR with their leisure time, as to some extent this mirrors the patterns found in the West. That is, the richer citizens preferred intellectual and active activities (study, art, scientific hobbies, and reading) while the poorer citizens preferred less intellectual and passive activities (radio and television, and what Matthews dubs 'relaxation and amusement').

One might wonder why this was the case. Why despite of having the explicit goal of ending poverty and the State commanding the resources of the whole economy they didn't manage to end poverty. From the analysis here and the other posts in the series, it seems that it was an issue of miscalculation: thinking that the poor were better off than they were, and that they were able to acquire the resources that they needed with the money that they had. To end poverty, the government would have needed to lower prices (but this would have caused further shortages), or implement a rationing scheme, like in contemporary Cuba. The fact that the study of poverty wasn't an ongoing activity - as poverty officially, like unemployment, didn't exist- surely made it more difficult for the State to deliver on their promises of a guaranteed existence for everyone. It is an open question for me whether in States with an extensive rationing system, poverty is effectively abolished.

What I sketched there could be explained in part by the low representation of the poor in politics, a factoid that is similar to what we find today in the West. In the Central Committee, one of the highest organs of Soviet politics, only 4.2% out of its 472 members (in 1981) were workers, 1.7% were peasants and 0.4% were low grade employees. In lower ranks of the State, there were more poorer citizens in their composition, but in none were they an established bloc.

Conclusion

The USSR managed to reduce inequality and poverty with respect to pre-revolutionary times, and it did deliver in bringing a level of equality comparable to that of Nordic social democracies. However, it wasn't successful in eliminating poverty, inequalities between republics, differences between the urban and rural areas, and even the 'distinctions between physical and mental work'. Though not mentioned here, Matthews observes that it was commonly regarded across social classes in the USSR that mental jobs were of higher status and more desired than physical jobs. At the end of the day, regardless of the ownership of the means of production, someone has to flip the burgers and sweep the floors, and that won't be as liked as other jobs.

It could be easily argued that the reason why these changes did not happen was the lack of political will. Could a mixed rationing/market system for consumer goods have solved poverty while keeping freedom of choice? Well, maybe. Would it have been possible to, through massive State investments, reduce the differences between the republics? Again, maybe. But in doing so, resources would have been detracted from elsewhere. Maybe if a rationing system ensuring 100% coverage were implemented, it would have severely affected the portion of production dedicated to individual choice. A study on the possibility of such a system would be interesting to undertake.

Notes

*WESW: Wage Earners and Salaried Workers. See the paper for the precise meaning of this.

Bibliography

Alexeev, M. V., & Gaddy, C. G. (1993). Income Distribution in the USSR in the 1980s. Review of Income and Wealth, 39(1), 23-36.

Bergson, A. (1984). Income inequality under Soviet socialism. Journal of Economic Literature, 22(3), 1052-1099.

Matthews, M. (1986). Poverty in the Soviet Union: the life-styles of the underprivileged in recent years. Cambridge University Press.

McAuley, A. (1977). The distribution of earnings and incomes in the Soviet Union. Soviet Studies, 29(2), 214-237.

Ozornoy, G. I. (1991). Some issues of regional inequality in the USSR under Gorbachev. Regional Studies, 25(5), 381-393.

Comments from WordPress

p 2017-03-27T17:38:29Z

If you had to recommend only one book about USSR, which one would you recommend?

(You can choose your own criterion)

Artir 2017-03-27T18:19:53Z

It depends on how interested you are and/or how much you know already. Basic: Red plenty Advanced: Economic History of the USSR (Nove) for the historic details, Allen's book for a more quantitative view, Janos Kornai's The Socialist System for an in-depth overview of socialism abstracted from any particular country.

- The Soviet Union series | Nintil 2017-03-14T22:49:43Z

[…] The Soviet Union: Poverty and inequality […]

Ian Wang 2017-03-14T23:10:54Z

I didn't see any mention in your excerpts of non-monetary income. Was that ever considered for the elites, as well? I remember professionals complaining bitterly of the elites who had the privilege of shopping in the Beryozkas. They could buy Western goods in rubles at a discount even to us Westerners (who had to use hard currency) and re-sell them, or simply live better, so not every ruble earned was worth the same amount - Party membership cards at the regional, Republic or national level made some rubles more equal than others.

In addition there were the free or subsidized apartments and dachas, cars and the like, that boosted elite incomes in ways not readily measurable in rubles.

This would not change the percentage in poverty, but it did significantly change the relative standard of living between elite and poor, and I believe it was much greater than 3X when you consider the lives of the highest nomenklatura, elite Olympic athletes, etc. At least that's what I observed in the late 80s.

I still remember buying some orange and grapefruit juice for a friend's birthday party the only time I ever shopped in a Beryozka (~1989). He had never had grapefruit juice in his life.

Artir 2017-03-15T17:22:31Z

Thank you for your comment.

Yes indeed you are right. Yesterday as I was going through the article one last time I remembered some paragraphs about privileges of the elites, but I couldn't find them because I was looking in Matthews' book. But I got myself confused: Matthew's wrote a book about the elites, which I couldn't access for this post. But the paragraphs I was looking for were in Bergson's article. I'm adding them this weekend.

Seva 2017-03-16T00:04:33Z

Absolutely right. Non-monetary income through "blat" and "nalevo", not to mention informal bartering networks, increasingly became preferred. By the time I left the Soviet Union, people were actively avoiding Soviet cash in favor of foreign and durable goods (as payment for services).

Great set of posts Artir. Made me want to re-read Red Plenty.

U know who 2017-03-15T23:24:49Z

¿Para cuando un libro de historia económica sobre la URRS?

U know who 2017-03-15T23:25:15Z

URSS*

Artir 2017-03-16T00:13:52Z

Quizá ocurra

Citation

In academic work, please cite this essay as:

Ricón, José Luis, “The Soviet Union: poverty and inequality”, Nintil (2017-03-14), available at https://nintil.com/the-soviet-union-poverty-and-inequality/.