The Soviet Union: Achieving full employment

[Part of the Soviet Union series]

The Soviet labour 'market' was a peculiar one. Rather than the prevalence of unemployment, as we are used to, the Soviet Union not only achieved full employment, but also got to a situation where there were_shortages of labour,_even though a significant share of the population was working. In this post I clarify what does full employment mean in the Soviet context, and explain some aspects of their labour 'market' not covered in my previous post on this topic. As usual, this post covers the post-Stalin era. [1]

The official Soviet ideology contends that socialism is not only completely different from capitalism, but also in all respects (i.e. socially, economically, politically, culturally, and morally) superior to it. In order to substantiate this claim, the ideology cites a long list of achievements, one of them being that while unemployment is an endemic feature of capitalism, socialism abolishes it entirely and once and for all.

If the term 'unemployment' denotes exclusively open unemployment of the registered kind or the dole, then the assertion is fully justified, because in the Soviet Union the payment of unemployment benefits was stopped as early as October 1930. On top of that, over the years the Soviet regime has succeeded in mobilizing for participation in the social economy the vast majority of able-bodied men and women of working age.*** (Porket, 1989)

This post draws mainly on János Kornai's The Socialist System (1992) and J.L. Porket's Work, Employment, and Unemployment in the Soviet Union (1989).

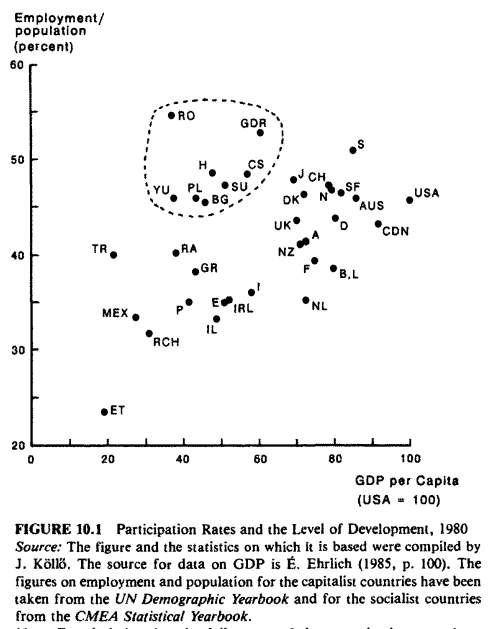

The first point I'll mention is the data backing up the claims in the introductory paragraph: The activity rates in socialist countries were far higher than the ones in the West

Kornai 1992

Kornai 1992

Kornai warns that economic development increases the participation rate, but even when taking this into account, the socialist economies still shine in that sense.

There is a loose positive relationship between the level of economic development and the participation rate. If one compares the participation rates of socialist and capitalist countries at the same level of economic development, it turns out that the socialist countries' participation rates are the highest on each level of economic development.

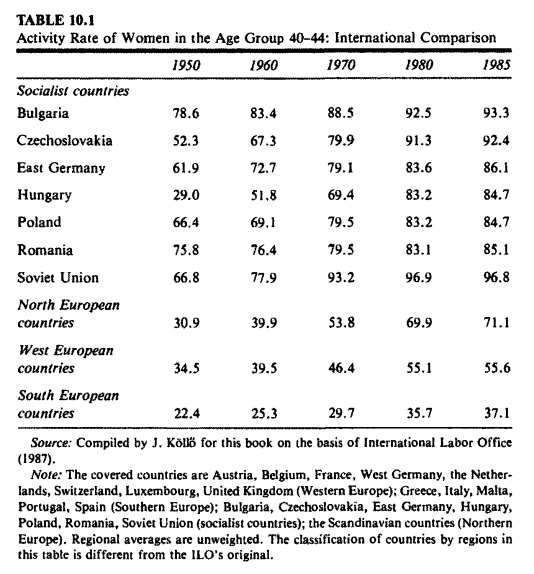

One key difference between the socialist systems and the West was a massive socialist lead in women's activity rate, which contributed to the overall participation rate. Assuming crudely that women are half of the population, in 1980, assuming South European levels of women's activity rate implies a difference of 61.2 percentage points. Half of that is roughly 30 percentage points, which then have to be translated to employment/population, which will be less, because not everyone works. While I don't have data at hand for this final step, it is plausible that the higher rate of activity of women explain a big part of this increased overall activity rate.

Kornai 1992

Kornai 1992

We could think that this was due to an underlying feminist trend, where the Soviet State pursued and achieved gender equality. In the West, women entering the workforce was a result of changing norms of what was admissible for women to do, where previously some occupations were seen as male-only. The reason for this increased women activity rate in the USSR was that the socialist system needed workers, and women make up half of the population. The feminist interpretation, that seems plausible given de jure legislation regarding maternity leave, for example, faces several issues, like the abortion ban (reversed after Stalin in 1955)[2] and legal barriers to divorce in 1936 (to encourage population growth), the fact that there were almost no women in the higher echelons of the Party, and that women were still the main carers of children and main doers of household chores (Mespoulet, 2015)

But why full employment and labour shortages? Kornai argues that this wasn't because of an explicit policy to ensure full employment (even though the right and the duty to work were enshrined in the Constitution of the USSR). Achievement of full employment was a by-product of the socialist system in its pursuit of growth. This right to work, however, wasn't present from the beginning, but it's granted once the system has reached a point where full employment obtains.

Once this process has occurred and been rated by the official ideology among the system's fundamental achievements, it becomes an "acquired right" of the workers, a status quo that the classical system cannot and does not wish to reverse. Thenceforth full employment is laid down as a guaranteed right (and to a degree, so is a permanent workplace, as will be seen later). This is an actual, not just a nominally proclaimed right, ensured not only by the principles and practical conventions of employment policy but by the operating mechanism of the classical system, above all the chronic, recurrent shortage of labor. Permanent full employment certainly is a fundamental achievement of the classical system, in terms of several ultimate moral values. It has vast significance, and not simply in relation to the direct financial advantage in steady earnings. It plays additionally a prominent part in inducing a sense of financial security, strengthening the workers' resolve and firmness toward their employers, and helping to bring about equal rights for women.

The situation of chronic labour shortage (In Poland, for example, there were over 90 vacancies per job seeker) is seen as problematic by the Party, as labour shortage means the productive plans are harder to fulfill, and so planners tend to react by investments in labour saving capital goods, promoting population growth, etc.

From the factory manager's point of view, this situation induces them to 'hoard' workers: perhaps more workers will be needed in the future, but maybe they will not be available for hire, so they hire them now. At a given point in time, then, a factory will have more workers than it actually needs. This, combined with low job activity from some (demotivated) workers leads to the concept that Kornai terms 'unemployment on the job'.

***While open unemployment of the registered kind is absent and the labour force participation rate is high, open unemployment of the unregistered kind has not disappeared. In addition, there is chronic and general overmanning as well as voluntary and involuntary employment below skill level, i.e. underutilization of employed persons in terms of both working time and educational qualifications. Although underutilization of employed persons keeps open unemployment down, it has a number of adverse consequences, which should not be overlooked. Amongst other things it contributes to slack work discipline, low labour productivity, divorce of rewards from performance, low real wages, inflation, and shortages of consumer goods and services. Thus, from the point of view of the situation in the labour market or the relation between the supply of and demand for labour the official Soviet economy may be characterized as a high-employment one; from that of the utilization of the employed labour force or the relation between labour input and the output of economic values it may be characterized as a low-productivity one; and from that of the income received by individuals for playing the role of employed persons it may be characterized as a low-incentive one. (Porket, 1989)

One way to think about this: Assume that we have two economies that consist of people digging ditches (people like ditches in this world) and related activities. Economy A uses the most efficient arrangement of people and capital for the task, but there exists some unemployment due to inefficiencies here and there, so that only 95% of working age people who want to work actually do so.

Economy B is the same as Economy A, but it has 100% employment, due to a government mandate that those who would be unemployed are to be hired. People take shifts to dig ditches.

At the end of the day, the same length/number of ditches are dug in both economies.

Some people would like Economy B: everyone has a salary, and people work less. Great, isn't it? But the problem is that -assuming no companies go bankrupt- a) Salaries are lower b) No extra labor is easily available for new projects c) Some people work and earn less than they would like to

At the end of the day, it comes to a redistribution of wages and work time: Some win and some lose. Alternatively, this could be seen as a tax on the employed to redistribute to the unemployed. But the economic consequences of doing that in the long term are problematic [3].

This is overmanning, a form of hidden unemployment. If Economy B actually used the efficient number of workers, they would have, say, an employment rate of 80%. In this case, the economy would be producing the same in aggregate.

Overmanning is a type of hidden unemployment. Porket distinguishes three kinds:

- Employment in part-time jobs when a full-time job is desired

- Employment where people are forced to work in jobs for which they are overqualified

- Employment where companies employ more people than they need, given their technological conditions (the case of Economy B)

He estimates overmanning to be 10-15% of the total workforce.

We now jump to post-Stalin history.

Between 1957 and 1961, so called 'antiparasite laws' were adopted in most of the USSR. These measures were to force everyone to have a 'socially useful work', and noncompliers were punished with 2-10 years of forced labour.

Some open unregistered unemployment existed, but was low:

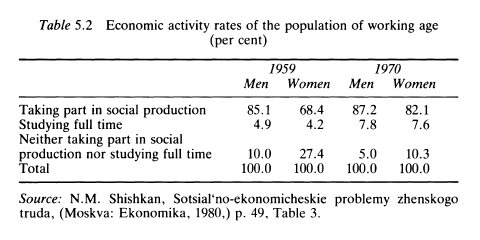

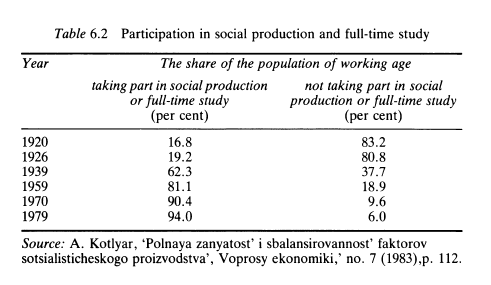

Not surprisingly, this open unemployment stemming from a lack of vacancies was not officially quantified, so that its accurate volume remains a guess. But it is known that in 1959 10.0 per cent of men of working age and 27.4 per cent of women of working age neither participated in social production nor studied full time (see Table 5.2 below). And six years later E. Manevich asserted that 20 per cent of the able-bodied population did not take part in social production. Obviously, the 1959 figures did not refer exclusively to jobless persons keen to have a job, yet unable to get it because of a lack of vacancies. They also covered non-employed persons uninterested in playing the roles of workers or collective farmers. Nevertheless, they clearly indicate the existence of at least some involuntary open unemployment, albeit unregistered. Concerning specifically youth unemployment, it was reported (although not documented) by Basile Kerblay that 'according to Gosplan statistics, 25.2 per cent of young people aged between 16 and 17 and 13.9 per cent of those aged between 18 and 19 were unemployed in medium-sized towns in 1965, compared with 1. 7 per cent for other age groups'.

Besides admitting the occurrence of both non-employment and involuntary open unemployment, naturally without using the term 'unemployment' which was reserved for capitalism, Soviet sources further admitted that employed persons were frequently underutilized, either because of involuntary employment below skill level, or because of overmanning.

In order to remove this particular cause of overmanning, E. Manevich proposed in 1965 and again in 1969 a solution that in fact amounted to open registered unemployment. Instead of enterprises, special organizations should be responsible for the placement of the workers made redundant in connection with technological progress. Simultaneously, while between jobs, the workers in question should be provided for materially by the state. Not surprisingly, the proposal was not implemented. Open registered unemployment and unemployment benefits were unacceptable to the regime, because its ideology contended that socialism liquidated unemployment entirely and once for all and that under it technological progress went hand in hand with full employment of the able-bodied population. Thus, restrictions on dismissals were not lifted, so that enterprises shedding surplus workers remained responsible for their placement. (Porket, 1989)

Under the (1976) constitution, citizens had the right to work (i.e. to guaranteed employment and pay in accordance with the quantity and quality of their work, and not below the state-established minimum), including the right to choose their trade or profession, type of job and work in accorance with their inclinations, abilities, training and education, albeit subject to the caveat of taking into account the needs of socieety. On the other hand, it was the duty of and a matter of honour for every able-bodied citizen to work conscientiously in his/her chosen, socially useful occupation, and strictly to observe work discipline. Socially useful work and its results determined a person's status in society. Evasion of socially useful work was incompatible with the principles of socialist society [...]

Moreover, the labour situation was contradictory. 34 On the one hand, open registered unemployment was absent, economic activity rates were high, full employment of the able-bodied population was alleged, and complaints of labour-deficit areas and a shortage of labour at the national level abounded. On the other hand, open unregistered unemployment was not unknown, overmanning at the enterprise level was chronic and general, quite a few qualified individuals were voluntarily or involuntarily employed below their skill level, labour-surplus areas were to be found, and employment in the official economy was evaded. This contradiction was reflected in Soviet discussions on the country's manpower resources. The prevailing view asserted that labour resources were inadequate, meaning by it that the available labour supplies lagged behind the effective demand that was incorporated in enterprise plans and backed up with funds. In contrast, a minority view contended that labour resources were completely adequate, but were utilized irrationally.

To sum up, the official unemployment rate was zero, almost by institutional definition: You couldn't sign up for unemployment benefits. Companies hoarded labour

However, non-registered unemployment existed for people who had quit their jobs and moved to another location, or had just begun working. While at an aggregate level, there were many more jobs than workers, in a micro scale, the geographical and skill distribution of these jobs did not match efficiently with the location and skills of the workforce. Despite this, the Soviet Union managed a very high employment rate, on par with the concept of full employment in the west.

Breaking down this by parts, a fraction were people switching jobs: since a) there were no unemployment benefits, people had lots of incentives to quickly look for another job. b) There were lots of vacancies c) 'Uninterrupted service' a legal concept that had an impact in social security benefits. If a worker was without employment for more than three weeks, they would lose that status d) Antiparasite laws that made punishable not having a 'socially useful' job for more than four months.

Other part of this unregistered unemployment were women who quit their jobs to be mothers.

Yet another part was youth unemployment. Young (<18) people were entitled to a variety of privileges, like having to work less hours for the same pay a full time worker would get. Ceteris paribus, companies preferred older workers. The USSR reacted to this by imposing quotas on companies (Between 0.5 and 10% of the workforce had to be <18). The rate of (unregistered) unemployment for this group was 1-5%.

Further, to easen up the transition from school or university to work, the State planned which companies would hire which worker in advance, which sounds like it would solve any problem, but

In practice, the system functions far from smoothly. It has difficulties in balancing supply and demand. There are exemptions from it, particularly on grounds of health and family circumstances. Due to changes in their plans or needs, enterprises frequently refuse to hire the graduates directed to them. Some graduates fail to show up at their assigned posts. Others do turn up, but leave before the expiry of the three-year period, inter alia, because they are not given work

Conclusion

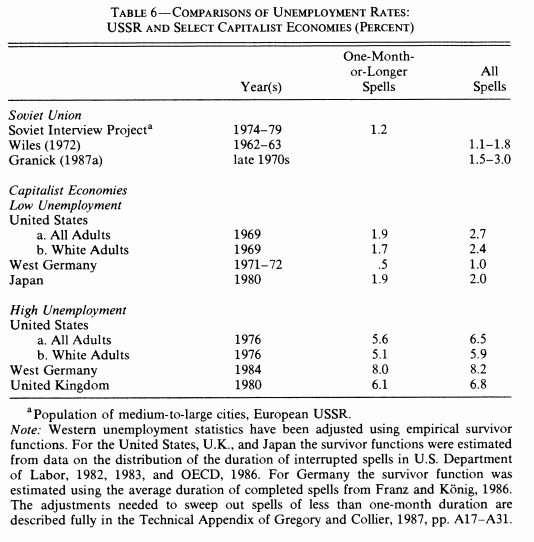

Taking into account unregistered unemployment the Soviet economy achieved what in the West is typically called full employment (At least in the sense that almost everyone who wanted to work had a job), with rates below 5%. This compares favourably with capitalist economies at their best, and it's significantly better than capitalist economies undergoing a recession (Gregory and Collier, 1988, Ellman 1979)

Gregory and Collier, 1988

Gregory and Collier, 1988

Rates of activity among women were high due to the need for more workers.

However, companies was plagued by overmanning due to the incentives mentioned above, and while measures were taken to try to reduce it, it still persisted.

References

David, H. P. (1974). Abortion and family planning in the Soviet Union: public policies and private behaviour. Journal of biosocial science, 6(04), 417-426.

Ellman, M. (1979). Full employment—lessons from state socialism. De Economist, 127(4), 489-512.

Field, M. G. (1956). The re-legalization of abortion in Soviet Russia. New England Journal of Medicine,255(9), 421-427.

Gregory, P. R., & Collier Jr, I. L. (1988). Unemployment in the Soviet Union: Evidence from the Soviet interview project. The American Economic Review, 613-632.

Kornai, J. (1992). The socialist system: The political economy of communism. Oxford University Press.

Mespoulet, M. (2006). Women in Soviet society.Cahiers du CEFRES, (30), 7.

Porket, J. L. (1989). Work, employment and unemployment in the Soviet Union. Springer.

Spufford, F. (2010). Red plenty. Faber & Faber.

[1] During Stalin's time, until 1956, workers couldn't legally quit their jobs without permission from the company's management. Quitting was a criminal offence. The State could compulsorily move workers from one company to another. Work discipline was enforced throughout the Soviet era, but the harshness of punishments decreased after Stalin.

Explicity, the official attitude was reiterated by L.F. Il'ichev in ecember 1961: communism and work were inseparable, communism was not a society of lazy-bones, an aggregate of loafers. (Porket, 1989)

Even after Stalin, worker strikes remained illegal, but some incidentsdid occur.

[2] An even then, it wasn't because of a greater respect for women's rights, but because women were having abortions anyways, and illegal abortions are generally less safe. The relegalisation decree wasn't publicised, to avoid further increases in abortion rates, which illustrates that the Party attitude towards abortion was closer to a technical problem (Will this measure promote growth?) rather than a matter of rights, which was closer to Lenin's views. (Field, 1956)

While no official policy has been publicly promulgated, much emphasis is placed on 'the fight against abortion'. Potential dangers are publicized through extensive dissemination of brochures, medical bulletins, posters, and related materials. Some Soviet literature expresses a sense of moral indignation and censures women seeking abortion. Most research focuses on possible somatic sequelae. As one Soviet colleague explained to me, 'Every child must be wanted . . . abortion is available . . . but we must restrict abortion in spite of the permission for abortion.' Legal abortion is viewed as only a slightly lesser evil than illegal abortion. (David, 1974)

[3] Both economies have the same citizens and preferences, so citizens in Economy A already have a job-length distribution that they like. In Economy B, people would want to earn more (by working more), but they can't.

What about the unemployed in Economy A? If there are unemployment benefits, that will come from the incomes of workers, so perhaps the final distribution of salaries could be the same as in Economy B. If there were no productivity losses from job and wages redistribution, it would be a zero sum game. If there are, however -and Porket mentions that that was the case - then forcing full employment makes everyone worse off in the aggregate, and in the long run.

Workers, having now an advantage over employers displayed less work ethic, absenteeism, and could threaten employers with leaving if they were to be disciplined (This, after the Stalin period).

[4] Under Stalin, higher education mostly meant engineering. Half of university students pursued degrees in engineering, the rest were pure sciences, agricultural sciences, and medicine. Humanities and social science departments were mostly defunded. (Spufford, 2011)

Comments from WordPress

- Morning Ed: Labor {2016.09.05} | Ordinary Times 2016-09-05T09:01:03Z

[…] How the Soviets achieved full employment. […]

- The Soviet Union series | Nintil 2016-07-30T16:33:13Z

[…] The Soviet Union: Achieving full employment […]

Biopolitical 2016-07-30T21:51:46Z

The Soviet Union had full employment and labor shortages simply because the government monopolistically set wages below the market-clearing equilibrium. Some firms avoided labor shortages by paying extra (in cash or in kind) under the table.

- Morning Ed: Labor {2016.09.05} | ePeak.info 2016-09-06T07:37:41Z

[…] How the Soviets achieved full employment. […]

- The Soviet Series: From farm to factory. Stalin’s Industrial Revolution | Nintil 2017-02-04T19:37:59Z

[…] workers had to be repressed and coerced into working as the State demanded. (I talked about this here and here) The problems the forced translation of labour from farm to factory caused with […]

123 2016-10-21T20:21:22Z

"At least in the sense that almost everyone who wanted to work had a job" 'not working' was illegal in ussr, you were forced to work.

- The Soviet Union: Productive Efficiency | Nintil 2016-11-07T21:49:51Z

[…] I think it serves as a first approximation. One possible explanation for this particular table is overmanning: Employing more people than necessary for a variety of reasons explored in the linked post. Other […]

Citation

In academic work, please cite this essay as:

Ricón, José Luis, “The Soviet Union: Achieving full employment”, Nintil (2016-07-30), available at https://nintil.com/the-soviet-union-achieving-full-employment/.

Comments