Stereotypes and discrimination against women in STEM

Yes, one more post about the Google memo. Here, I review the evidence that was put forward to support the idea that the gender gap in STEM participation (especially in engineering) is due to stereotypes and discrimination.

Admittedly, I haven't discussed much this topic on my previous posts, as I have a strong prior against this hypothesis, and the evidence I have presented points to a strong role for biology (And there are other things I want to read and write about!). But if one thinks that the role of stereotypes and discrimination is big, then by implication one will think than that of biology is small. As the Moorean shift goes, one man's modus tollens is another man's modus ponens. Since no one else is going to do it, here I will discuss the other side of the question that I have ignored: how strong is the evidence for the negative cultural hypothesis? In what follows, I limit myself to evidence presented during the debate. Due to the recent meta-analysis cited in one of my previous posts, I will dismiss directly references to stereotype threat.

The best collection to start is Rachel Thomas'post and this otherone.

If you think women in tech is just a pipeline problem, you haven’t been paying attention (Thomas)

When researcher Kieran Snyder interviewed 716 women who left tech after an average tenure of 7 years, almost all of them said they liked the work itself, but most were unhappy with the work environment.

From the linked article:

Over lunch, she confided in me that she was thinking of quitting. It was too hard to juggle everything. Her manager had pressured her to return from leave early, and was pushing her again to take a business trip and leave her nursing infant at home. She wasn’t sleeping. She felt like she was failing her job and her child at the same time. [...]

Many women said that it wasn’t motherhood alone that did in their careers. Rather, it was the lack of flexible work arrangements, the unsupportive work environment, or a salary that was inadequate to pay for childcare. As Rebecca, a former motion graphics designer, put it, “Motherhood was just the amplifier. It made all the problems that I’d been putting up with forever actually intolerable.”

So far, this is just a tradeoff between different life projects: work and family, no discrimination here. Here there is, though:

One-hundred-ninety-two women cited discomfort working in environments that felt overtly or implicitly discriminatory as a primary factor in their decision to leave tech. That’s just over a quarter of the women surveyed.

So just over a quarter: The vast majority of women did not perceive any discrimination. The data and/or report itself are not available for further comment. Back to Thomas:

In NSF-funded research, Nadya Fouad surveyed 5,300 women who had earned engineering degrees (of all types) over the last 50 years, and 38% of them were no longer working as engineers. Fouad summarized her findings on why they leave with “It’s the climate, stupid!”

In that article:

From the aerospace sector to Silicon Valley, engineering has a retention problem: Close to 40 percent of women with engineering degrees either leave the profession or never enter the field.

The linked report does not consider the obvious control: men. How many men leave engineering? If we found that also 40% of men with engineering degrees are not in engineering, the picture would greatly change, as it would show that it is not because of discrimination that they leave, but due to more benign factors (not liking the job itself, or finding a better job elsewhere)

The report doesn't really mention discrimination or hostility as a factor for they leaving. The testimonies included suggest that it was the long working hours and requirement for high availability that discouraged them. One of the slides mentions that , for the group that left engineering less than 5 years ago, two thirds left to pursue better opportunities in other fields, and a third left to stay at home. Another interesting result is that there is no differences by industry in terms of perceptions of supportiveness: the field of bioscience is as supportive of women as computer science. Hence, different support wouldn't explain the computer science vs bioscience gender gap.

There is some work that addresses the male vs female retention issue. Kahn & Ginther (2015) for example cite other work that shows that also many men leave STEM. On industry jobs, one of the studies cited, by the Society of Women Engineers, finds that for the cohort who graduated in 2003-2005, 60% of women stayed in STEM, compared to 70% of men, so a gap of 10%. The study also mentions that equality of treatment in engineering is improving. In 1993, 15.3% women engineers reported "consistent inequities in treatment for male and female workers doing the same job". In 2005, it is down to 9.6%, according to women. According to men, the numbers are 6.6% and 3.2%.

The study also discusses why men and women leave STEM, and only a small number of women mentioned negative work climate issues for leaving throughout the years (10%), while 5% of men left for the same reason. The main reason cited by both groups were interest in other careers, followed by advancement opportunities and lack of challenge.

Kahn and Ginther's paper concludes:

Family status is of key importance. Women with children are most likely to leave the labor force and therefore engineering. Single women without children are actually less likely than men to leave engineering (by the 7–8 year point) for 4 of the 5 cohorts.

Similarly, women who remain working full-time on average are somewhat more likely than full-time men to remain in engineering jobs through the 3–4 year post-BSE point, and equally or more likely 7–8 years post-BSE for four of the five cohorts. Dividing by family status, single women without children who work full-time are more likely to remain for four of the five cohorts at the 7–8 year point and even women with children are equally likely to remain for 3 of the 5 cohorts.

This makes the 40% of women leave engineering statistic less catastrophic, and emphasises the role of preferences for work hours and family. Discrimination, as per these studies, looks like a minor thing.

Back to Rachel Thomas:

- Investors preferred entrepreneurial ventures pitched by a man than an identical pitch from a woman by a rate of 68% to 32% in a study conducted jointly by HBS, Wharton, and MIT Sloan. “Male-narrated pitches were rated as more persuasive, logical and fact-based than were the same pitches narrated by a female voice.”

The study finds that a pitch delivered by a male is 1.57 times more prefered than the same pitch delivered by a woman.

But this is not the only study that analyses this issue. Boulton et al. (2017) studied pitches to angel investors in the US television program Shark Tank, and did not find a gender effect. Nor did Ewens & Townsend (2017) find that effect on a study of AngelList (A platform that allows investors and startup founders to interact). What these two studies found, however, was some degree not of discrimination but homophilic bias: male investors prefer male entrepreneurs and female investors prefer female entrepreneurs.

- In a randomized, double-blind study by Yale researchers, science faculty at 6 major institutions evaluated applications for a lab manager position. Applications randomly assigned a male name were rated as significantly more competent and hirable and offered a higher starting salary and more career mentoring, compared to identical applications assigned female names.

This is the Moss-Racusin et al. (2012) study, which fortunately has already been discussed for my by Lee Jussim (ht/ to Francisco Boni for the pointer), says Jussim:

"The Moss-Racusin study is, by conventional standards, the weakest of the studies. Its sample size is a fraction of that of the others. It studies a relatively minor situation (hiring lab managers). It was a single study (Su et al is a meta-analysis of scores of studies; Williams and Ceci reported five separate studies). In contrast to Wang et al, it only studied an event at a single time point; it did not follow people’s career trajectories.

This does not make Moss-Racusin et al a “bad” study; it is merely weaker on virtually all important scientific grounds than the others. This is not to argue that the other studies are “perfect,” either; all studies have imperfections. But by conventional scientific standards, Su et al's meta-analysis, the replications in Williams and Ceci, the longitudinal Wang et al study, and the far larger sample sizes in all three mean that, on most scientific methodological standards, they are superior to the Moss-Racusin et al study.

And yet, look at the citation counts. Others are citing the Moss-Racusin et al study out the wazoo. Now, Wang et al and Williams and Ceci came out later, so probably the most useful column is the last. Since 2015, the weaker Moss-Racusin study has been cited 50% more often than the other three combined! That means there are probably more papers citing the Moss-Racusin et al study and completely ignoring the other three, than there are papers citing even one of the other three! What kind of "science" are we, that so many "scientists" can get away with so systematically ignoring relevant data in our scientific journals?

(Again, this does not make the Moss-Racusin study “bad.” The bias here reflects a far broader field problem, it does not constitute a weakness in the paper itself).

And that, gentle reader, is a gigantic scientific bias. It might even be beyond bias. Some might call it an “obsession” with discrimination and bias so severe that it is blinding many in our field to major findings regarding gender differences that contribute to preferences for different types of fields"

Thomas:

- When men and women negotiated a job offer by reading identical scripts for a Harvard and CMU study, women who asked for a higher salary were rated as being more difficult to work with and less nice, but men were not perceived negatively for negotiating.

The study also showed that a candidate being female was related to a higher willingness to work with her when the evaluator was male. No such effect was seen when the evaluator was female. And the study also showed that some degree of homophilia may be at play (Table 2). In rating willingness to work, men only rated women lower (d=1.14), while women rated both men (d=1.16) and to a lesser extent women (d=0.6) lower. In niceness, men only rated women as lower whey asked for a higher salary (d=0.66), and women ranked both men (d=1.41) and women (d=1.23) as less nice. A similar effect was present in demandingness.

This is, to be sure, something that should not be happening. Homophilia is an anti-women and anti-men bias, held by men and women, respectively.

That said, I agree that this study does reveal an overall discrimination against women. But is it relevant to explain the STEM gap? (The study considers a scenario where participants want to be assigned to a more senior management position and they are interviewing for that position)

- Psychology faculty were sent CVs for an applicant (randomly assigned male or female name), and both men and women were significantly more likely to hire a male applicant than a female applicant with an identical record.

I couldn't access the paper, which seems to be from 1999 and for psychology, not STEM. However, for STEM we do have a recent study (Williams & Ceci, 2015a), and they found that there is a 2:1 preference FOR women in hiring decision for STEM tenure track positions. This holds across biology, engineering, and psychology. For economics, preference is about 1:1.

Some were critical of this study, but later on the same year they replied to some criticism in a later study (Williams & Ceci 2015b). Specifically, a critique was that because of the design of the study of Williams and Ceci, it wouldn't capture the full extent of discrimination, as it reduced the candidates to numbers, plus a tag with gender. The however, pre-empted this critique:

“Such ranking experiments have nothing to do with real-world hiring.” As we noted, women have significant advantages in actual, real-world hiring—they are hired at higher rates than men. Some of our critics seem reluctant to acknowledge this fact, which is shown clearly in multiple audit studies that analyze who is actually hired at universities in the U.S. and Canada (see cites in Williams and Ceci, 2015). To argue that our experiment has no relevance to real-world hiring seems unpersuasive in view of the fact that in the real world of academic hiring women also are chosen over men in disproportionate numbers. As one commentator noted in arguing for the relevance of the current experimental design: “One would have to say both that women are, in fact, stronger candidates (which is one strong assumption for which there is no direct evidence), implying that faculty don't prefer them over equally qualified men in real hiring contexts, and that, nonetheless, faculty DO prefer them in hypothetical situations (another strong assumption for which there is no direct evidence). By far the most sensible explanation is the most economical one: faculty prefer women both in the hypothetical case and the real case; their preferences don't swing wildly from the actual to the hypothetical.”

The citations that they mention:

- National Research Council (2009) Gender Differences at Critical Transitions in the Careers of Science, Engineering and Mathematics Faculty (National Academies Press, Washington, DC).

- Wolfinger NH, Mason MA, Goulden M (2008) Problems in the pipeline: Gender, marriage, and fertility in the ivory tower. J Higher Educ 79(4):388–405

- Glass C, Minnotte K (2010) Recruiting and hiring women in STEM fields. J Divers High Educ 3(4):218–229

- Irvine AD (1996) Jack and Jill and employment equity. Dialogue 35(02):255–292

- Kimura D (2002) Preferential hiring of women. University of British Columbia Reports. Available at: www.safs.ca/april2002/hiring.html. Accessed March 18, 2015

- Seligman C (2001) Summary of recruitment activity for all full-time faculty at the University of Western Ontario by sex and year. Available at: www.safs.ca/april2001/ recruitment.html. Accessed March 18, 2015.

More in their appendix, pg. 26.

Back to Thomas

Performance reviews of high-performers in tech, negative personality criticism (such as abrasive, strident, or irrational) showed up in 85% of reviews for women and just 2% of reviews for men. It is ridiculous to assume that 85% of women have personality problems and that only 2% of men do.

This is again the same Kieran Snyder we mentioned before, with a sample size of 248, and again there is no source data available, or no peer-reviewed paper behind. I'm no peer-review nazi, but I I use the fact that something is peer-reviewed and open to give it more weight, and so should you.

Bias is typically justified post-hoc. Our initial subconscious impression of the female applicant is negative, and then we find logical reasons to justify it. For instance, in the above study by Yale researchers if the male applicant for police chief had more street smarts and the female applicant had more formal education, evaluators decided that street smarts were the most important trait, and if the names were reversed, evaluators decided that formal education was the most important trait.

The study has a sample size of 73, and the result is what it says, with p~0.01. There is more recent work on that area, including a meta-analysis (Koch et al., 2015). The meta-analysis itself is of laboratory experiments in hiring, but they mention field studies, where meta-analysis report that in the real world, bias is small, and if anything, in favour of women.

In meta-analyses of field studies, both Bowen, Swim, and Jacobs (2000) and Roth, Purvis, and Bobko (2012) reported small overall effect sizes for male–female differences (overall d values of .01 and .11, respectively, with females receiving higher scores than males), but gender differences varied across moderators such as gender stereotypicality of the rating measure, rater gender, and type of rating. One advantage of these meta-analyses of field studies assessing gender differences in ratings is the use of actual employee evaluations, allowing for increased confidence in the generalizability of findings. However, one drawback is the inability to unambiguously attribute gender differences in field studies to any particular cause, such as gender bias or true gender differences in performance.

The study reports a ream of findings, including an overall small pro-male bias. But they also found that those effects become really small for highly experienced raters (vs undergrads), and people who felt that their hiring decision was important, which is the setting for hiring decisions in the real world, thus explaining why the field studies didn't found any bias.

The study also says that bias is greater when the skill of the applicant is uncertain. But even this bias could have some degree of justification. If one has a background prior that men on average will fit better in that job (for whatever reason), then on receiving noisy information about two equal candidates of different genders, one has to - to comply with Bayes' theorem - opt for the male for the reasons discussed here. Now, is one justified in having such a prior? Well, if one accepts that the average man fits better than the average woman in that job, and accepts that, even when the population that applies for the job is self-selected, there is some noise in that self-selection, then one can be justified. Noise here means that women or men who won't fit in the job apply regardless.

I don't claim that it is the case here, but that it could be.

Why men don't believe the data on gender bias in science

This second article cites:

One early study evaluated postdoctoral fellowship applications in the biomedical sciences and found that the women had to be 2.5 times more productive than the men in order to be rated equally scientifically competent by the senior scientists evaluating their applications. The authors concluded, “Our study strongly suggests that peer reviewers cannot judge scientific merit independent of gender. The peer reviewers over-estimated male achievements and/or underestimated female performance.” The study finds that “gender discrimination of the magnitude we have observed… could entirely account for the lower success rate of female as compared with male researchers in attaining high academic rank.”

The study is correct and proves what they say (N~100). However, from that the article goes on to say

These are just a few of the hundreds of peer-reviewed studies that clearly show, on average, the bar is set higher for women in science than for their male counterparts.

But this doesn't seem to cohere well with the Williams-Ceci study and the literature citen therein. Indeed, in another paper (Ceci et al. , 2014) they directly address this paper, showing that it the literature does not in general point in that direction:

Sex biases in grant funding rates. Numerous commentators have claimed that sex bias in grant review is responsible for fewer women getting funded (or getting funded at lower levels) and that this failure to gain grants is responsible for women’s lower rate of persistence and lower rate of promotion. For example, Lortie et al. (2007) wrote that “it is now recognized that (sex) biases function at many levels within science, including funding allocation, employment, publication, and general research directions” (p. 1247). Notwithstanding such claims and myriad others (e.g., Wenneras & Wold, 1997), there are no systematic sex differences in grant-funding rates, although men’s grant awards tend to be for higher dollar amounts, likely as a result of men’s greater likelihood of being principal investigators on large center grants and program projects. Overall, however, men and women have very similar funding rates for their grant proposals (e.g., Jayasinghe, Marsh, & Bond, 2003; Ley & Hamilton, 2008; Marsh, Bornmann, Mutz, Daniel, & O’Mara, 2009; Mutz, Bornmann, & Daniel, 2012; Pohlhaus, Jiang, Wagner, Schaffer, & Pinn, 2011; RAND, 2005) Below, we summarize this literature. In the aftermath of Wenneras and Wold’s (1997) finding of biased grant reviews of 114 Swedish postdoctoral fellowships, many have claimed that women’s success in tenure-track positions is stymied by biases in grant awards, arguing that for a woman to be funded, she had to have on average 2.5 more major publications (i.e., in top journals) than comparable male competitors to get the same score. However, a comprehensive analysis of the data does not accord with this claim, and the full corpus of evidence does not reveal an anti-female bias in grant reviews (Ceci & Williams, 2011).

The Moss-Racusin study is also cited, already discussed.

If these studies at best suggest anti-female biases are not very strong (in STEM) and at worst they are nonexistent, why do people think that they can play a strong role? Because many scientist do think so. Maybe it is them who are biased. An example of this situation can be found in this series of posts by Lee Jussim (1, 2, 3).

Sources from the comments

Commenter "Alex" also left some evidence for stereotypes in my past posts:

1. Cracking the gender code (Accenture report), but it does not mention stereotypes or biases.

2. Why do so many women who study engineering leave the field begins with the already discussed Fouad article, continues with a panel survey by the author herself. It shows that women have less self-confidence as men and it was more likely that they would seek reassurance from others, compared to men who had lower self-confidence. It then goes on to show a few real instances of sexism, as an example:

For many women engineering students, however, their first encounter with collaboration is to be treated in gender stereotypical ways, mostly by their peers. While some initially described working in teams positively, many more reported negative experiences. When working with male classmates, for example, they often spoke of being relegated to doing routine managerial and secretarial jobs, and of being excluded from the “real” engineering work. Kimberly wrote, “Two girls in a group had been working on the robot we were building in that class for hours, and the guys in their group came back in and within minutes had sentenced them to doing menial tasks while the guys went and had all the fun in the machine shop.”

The paper itself, Seron, Silbey et al. (2015) has a sample size of 40 students (for the diary section, which is used a basis for the claims in the article, plus interviews with 100 students, in year one and two), and does not quantify the extent of this discrimination, just says that sometimes it was experienced.

The sample size of 700 mentioned in the article and the paper is Cech et al. (2011) does not discuss discrimination or sexism.

3. The 5 biases pushing women out of STEM mentions the Moss-Racusin study again, then Reuben, Sapienza, and Zingales (2013).

This paper studies hiring decisions in a laboratory settings. Subjects complete n arithmetic test, and them some of them are chosen as employers and have to ire others from the group. They do so under different scenarios: No Information (just looking at employees), Cheap Talk (candidates communicate their performance to the employer), Past Performance (Employers are told the employee's score), Decision Then Cheap Talk (employers chose a candidate to hire based on just their looks, then they were given the candidates' self-reported scores, finally, Decision Then Past Performance is the same as the previous one, but with the real score. The number of subjects per condition was around 50-60, and the number of picking decisions ranged from 160 in Cheap Talk to 269 in Decision Then Cheap Talk.

When no information was given, women were chosen 33.9% of the time, similar to the Cheap Talk scenario. When past performance was given, women were chosen 43% of the time. The article mentions that men were twice as likely to be chosen, but this was in the unrealistic condition where no information was available.

The next paper cited within 3. is Gender Bias Against Women of Color in Science .Their subjects were recruited by sending emails to the Association for Women in Science's members. This introduces a double self-selection problem which makes me highly suspicious of this study, regardless of the conclusions. First, women who have suffered sexism would be more likely, it would seem, both to join the association, and to put themselves forward for this study.

4. Discrimination in STEM links to one source about discrimination: the one we just saw

5. Why does John get the STEM job rather than Jennifer? Is a discussion of the Moss-Racusin study.

6. Are US millennial men just as sexist as their dads?

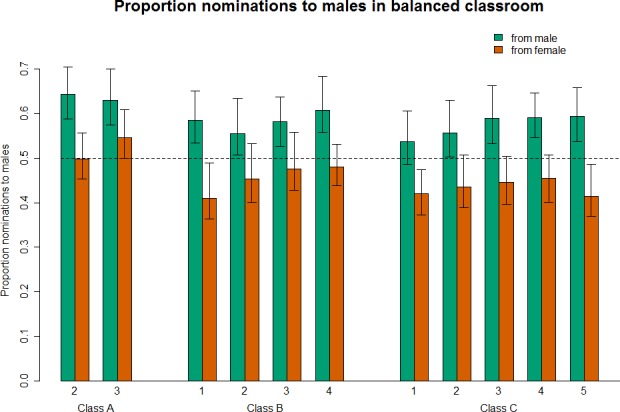

In February 2016 researchers at the National Institutes of Health published a study on how college biology students view their classmates’ intelligence and achievements. The researchers found that male students systematically overestimated the knowledge of the men in their classes in comparison with the women. Moreover, as the academic term progressed, the men’s faulty appraisal of their classmates’ abilities increased despite clear evidence of the women’s superior class performance. In every biology class examined, a man was considered the most renowned student — even when a woman had far better grades. In contrast, the female students surveyed did not show bias, accurately evaluating their fellow students based on performance. After studying the attitudes of these future scientists, the researchers concluded, “The chilly environment for women [in the sciences] may not be going away anytime soon.”

The graph below, from the paper, shows a simulation of how the distribution of nominations would look like assuming that a classroom is 50:50 male:female, that each group has the same distribution of outspokenness, and same for achievement. In the paper they study three different classes. By design, if no bias was present, the proportion of males would be 0.5 As you can see below, men show an average bias of 10% across all classess, while women show an average bias of what seems to be -5% (in favour of women)

In a 2014 survey of more than 2,000 U.S. adults, Harris Poll found that young men were less open to accepting women leaders than older men were. Only 41% of Millennial men were comfortable with women engineers, compared to 65% of men 65 or older. Likewise, only 43% of Millennial men were comfortable with women being U.S. senators, compared to 64% of Americans overall. (The numbers were 39% versus 61% for women being CEOs of Fortune 500 companies, and 35% versus 57% for president of the United States.)

The link does not link to the Harris Poll, and in the linked poll there is no reference to millennials.

Preferences: still the elephant in the room

The studies above deal with issues like sexism, inaccurate stereotypes and various biases, but they do not deal with what seems to be the root cause of the gender composition of the STEM fields: preferences. As we have seen, almost everyone who has looked into the issue, from psychologists to sociologists, seem to point to preferences as the key driver. But then the paths diverge: some argue that those preferences are just due to culture, others that biology also plays a role. Normatively, I have to emphasise, this does not settle anything. If it's all biology, one can still say that it has to be corrected, like male's greater propensity for violence.

So: Are girls and boys raised differently in those aspects that would later manifest in different choices of career? I welcome papers about that.

Citation

In academic work, please cite this essay as:

Ricón, José Luis, “Stereotypes and discrimination against women in STEM”, Nintil (2017-09-09), available at https://nintil.com/stereotypes-and-discrimination-against-women-in-stem/.

Comments