On the causal powers of Mormonism [revised]

How much truth is there to these statements? (The ones before the revision!)

My prior belief is that religion will have nonexistent or weak effects on the variables of interest. Religion is often intertwined with social class, and/or ethnicity, and so one has to look at diverse breakdowns of the data and compare if possible across time and countries.

(Edit: This post looks at both individual level and aggregate levels. At the individual level it is easier to discern causality, while the aggregate level helps us consider emergent effects)

Random faith

A good way to see what something causes is with a randomised control trial. However, it seems difficult to force people to believe in one or other religion at random. Instead, it may be possible to ask people to follow the behaviours that an adherent or that religion would follow (in matters of prayer, common rituals, dietary requirements, and so on).

Another alternative is to look at twins separated at birth, and raised in families similar in all relevant demographic variables but religion.

It is also important to remark that the first approach may be useful to see exactly what component of the bundle of behaviours that religion cause is the one linked with which outcome, unless it is sheer belief that is the causal force.

This also hints at a conceptual difficulty: Imagine that it is found that Mormonism leads to, say, lower lifetime poverty, the causal mechanism being a high savings rate that builds up a reserve of cash for when adversity hits. Then, one could argue that it is the savings, not the religion that is doing the job here. But then, it could be argued, that there are individuals that are too irrational to save on their own, and that for them, one irrationality might be fought with another: absent religion they would save less.

Been there, said that

In my review of The Elephant in the Brain I noted that the effects of religion seem overblown, or not generalisable:

Overall, most of the literature is correlational in nature, and attempts at causal analysis were few. Some interesting heterogeneous patterns emerged from the review, and SH’s core conclusion is correct in general: Religion is not harmful to individuals and in some cases it does seem to have a positive effect, with the caveats that follow the discussion below.

For physical **health related outcomes, **most papers indeed find that religious people are healthier across a range of measures in different countries, but causality has been in general difficult to ascertain. A recent paper that tries to address these concerns ended up finding a negative relationship instead for a sample of European countries plus the US (Berggren and Ljunge, 2017). So the conclusion may be that healthier people are more religious, but that if you take a person and “apply” religion to it, you get worse health. I acknowledge this is a non-peer reviewed work, but it is the only published so far that tries to go beyond correlations. Some weight has to be given to this one for trying to look at causality, but the rest of the literature is still there, so I wouldn’t claim religion is harmful just because of that paper yet.

For mental health and happiness, the Wink et al. paper focuses on the elderly. Initially no relation was found, but on a deeper look, a peculiar relationship emerged: Among those in poor health, religion reduced depression, but the opposite effect obtained for those in good physical condition.

A recent paper (Diener and Tay, 2011) tried to answer the question that, if religion is so good, why are people leaving it? As one climbs higher in the scales of education, wealth, and intelligence, across individuals and countries, one finds less religion. But why are they leaving it? SH have said that individuals generally know what is good for them (and I agree). Could it be here that individuals know that they are trading off earnings, health, and happiness against the truth?

The paper found that – as one might expect – living in diffcult conditions makes one more religious. Positive correlations were found between religion and subjective wellbeing (SWB) after controlling for life circumstances, in the US and in the world more broadly. But in less religious countries, there was no relation, a pattern similar to other studies. (Snoep, 2007, Stavrova, Fetchnhauer, and Schlösser, 2013). So maybe religion makes you well adjusted if you fit in better with those who surround you if they are also religious, but not if they do not.

For earnings, Steen’s paper interestingly decomposes the results by religion. Catholic men earn more than Protestant men, and Jews earn even more. The usual explanation for the salubrious effects of religion seems to operate through either more subjective happiness due to belief, and more importantly, through having a stronger supportive community. But here we find differences withing religions, and importantly, that non-religious men earn as much as Protestants. Maybe catholics have a super-strong work ethic that Protestants do not have (?)

In a different country, Canada (Dilmaghani, 2011), religion in general is found to have a negative effect, but again Jews have higher wages. (This makes sense). But in a more recent paper, decomposing results by province, differential effects were found: religion predicted higher wages in religious areas, but lower wages in less religious areas. (Dilmaghani, 2016). This goes with the religion-to-fit-in idea.

Similarly, in a German sample (Cornelissen and Jirjahn, 2012) – but note that this is a working paper – religion was found to have negative effects on wages, but oddly being raised by religious parents and then becoming and atheist raised earnings.

In the US, coming back to the Steen paper, Steen himself did another study some years after the one mentioned by SH (Steen, 2004). Catholics were again the ones found to be earning more. For a generic religion-is-good-for-earnings theory, this doesn’t seem to be what it would predict. (May there be hard to discern ethnic correlations behind?)

At a more macro level, besides the notorious inverse correlation between income and religion at a national scale, studies at a county level in the US show negative or neutral effect of religion (Rupasingha and Chilton, 2009)

And finally, a recent study (Herzer and Strulik, 2016) looking at a national level (in Western countries) considering causal effects find that both income reduces religiosity, and that lower religiosity increases income.

In general, it appears that religion does have some positive effects that materialise themselves through increase community participation. However, evidence on changes of faith causally inducing those is nonexistant, thus I wouldn’t recommend anyone to try to acquire belief (As Hanson seems to recommend here) in pursuance of a better life.

As a final note, some of the findings above may change if one considers non-linear relationships: It has been argued that if one compares highly religious and highly atheistic (Where highly here means that they have high conviction), both of those groups have better mental health and wellbeing compared to those who are weakly religious (As noted by Galen, 2015, and Galen and Kloet 2011 ).

But...

The above was a general review of the literature, done a few months ago as part of a wider article, so it is not as thorough as it could possibly be. Also, those papers were for religion in general, not the particular case of mormons.

[EDIT 2019-01-02: The effects described in this RCT fade out two years after they are measured, see here]

Besides the papers above, I have to mention some that were released since I wrote that: Bryan, Choi and Karlan (2018) found that teaching Protestant values to ultra-poor Filipinos raises their income (by 9%!). It's a pre-registered RCT with randomization at various levels, and controls. They measure many variables, and find that those who received the intervention were more religious and had their incomes increased, in contrast with those that did not. They also used a different surveying organization for the followup survey 6 months later to avoid biased responses. And they even studied the variables within households to see if the increase in income was concentrated in the family member that got the treatment, and it was. The only puzzle may be that other variables (assets, or consumption) did not increase. The authors address these and other points in the paper and the results seems convincing to me. This paper alone has shifted my belief that religion cannot have substantial positive effects: Now I think it is more likely that it can. Nonetheless, because of my experience with the pre-school interventions literature, one'd have to wait one or two years to see if the effects are permanent, or if they wash out, and, as the authors acknowledge, this may not be transferable to other cultures and settings.

The causal channel they posit is the increase of grit (As in Duckworth's grit). Grit has come under attack recently as a construct (See this meta-analysis) but that's just because it's picking up something already established and similar: conscientiousness, so this does not invalidate their findings.

The paper also looked at changes in consumption of alcohol, cigarettes, and arguments with a partner about alcohol consumption. No significant effects were found for those for the group treated with Protestantism.

In developed countries, there's Gruber (2005) and Gruber and Hungerman (2008), which I should have included. Gruber found, in the US that a 10% increase in religious density leads to a 0.91% increase in household income. He calls that effect substantial, but it doesn't seem that big to me, at least not compared to the one from the Bryan et al paper. The second paper finds that repealing laws that ban certain activities on Sundays ("blue laws") lead to an increase in cocaine and marihuana consumption. (In their sample, for example, 11% of the sample had consumed marihuana in the past month. The effect of repealing the laws in their model is an additional 3.2%). Note also that the models here, while obtaining economically and statistically significant results, have low predictive power for any given case (R2~0.1).

Another recent paper, Kuran (2018) analyses the effects of Islam on economic performance, finding it generally negative. On the one hand, this goes with the finding that religion correlated with less developed countries at an aggregate level, perhaps religion is good for you but bad for we. Or perhaps it's something specific to Islam.

If it seemed like religion works for the very poor but not for the very rich, from some papers above, there is also a paper for that (Bettendorf and Dijkgraaf, 2010), arguing that actually those in poor countries would see their incomes reduced from more religion. (Again, this is a correlational study)

Juck, Bentley and Lawson (2018) in a paper previously linked here at Nintil, found that secularization preceded economic growth (and that tolerance for individual rights was an even better predictor). Is religion good for you but bad for us, a prisoner dilemma of sorts?

Park (2018) finds evidence that the religion-health association in the US is non-causal, using a semi-experimental design that exploits law changes (especifically, the repeal of "blue laws", that restrict secular activities on weekends, thus decreasing religious activity

The most comprehensive one, albeit it's only for the specific topic of economic development is probably Basedau, Gobien and Prediger (2018), a proper literature survey. It's Stubborn Attachments season, and economic growth is an evergreen Nintil topic, so I had to mention it. One thing I have to mention from the start is it seems to suggest that religion is not disappearing, because the % of world population that is not religious is shrinking somewhat. But this is misleading: This is because highly religious populations are expanding faster than non-religious populations. But within countries, religion if anything is going down.

Other that that, the paper is quite good in breaking down religion into components, considering separately ideas, practice, or identity, and looking at -specific- causal mechanisms instead of stopping at mere correlation.

What the paper finds is that

- No clear evidence about religion->ethics/thrift/workethic/->economic growth

- No evidence that Religion-> work ethic -> economic growth

- No evidence that Protestantism -> economic growth

- Religion->resource consumption in religious activity-> less growth

- Religion->anti-innovation attitudes

- Religion-> prevention of harmful behaviour (drugs, alcoholism)

- Religion->discipline-> more years of education

- Inconclusive evidence about religion->prosociality

Finally, we can have a deeper look at subjective well-being (SWB). While self-report is an imperfect measurement technique and subjective variables are intrinsically hard to measure, this one variable should gather in one place the effects of religion on people.

An early meta-analysis (Witter et al., 1985) found a small (d=0.16) effect of religion on SWB. I couldn't find later meta-analysis on the same topic.

The results so far, with the extra papers I've looked, especially the RCT, have moved my opinion in the direction I mentioned above: I underestimated the causal effects of religion. However, that may not be enough: Because of the low explanatory power (as measured by R2) of models, "be more religious" will not necessarily lead to a sure improvement in the quality of life of any one given person, thus imposing an expected loss (the cost of engaging in religious activity if one does not find it intrinsically rewarding) to get a tiny chance of better outcomes. At a high level, the level that matters for economic growth, religion still has not proven to be a driver of it. Thus recommending any one person to try to become more religious is not a good recommendation, beyond generic recommendations of "be careful with alcohol and drugs".

Mormons

In what follows, I will analyse Mormonism. The reason for this is that it is a religion with a prescriptive health code (no tea, coffee, alcohol, tobacco, or drugs), and one that has a high degree of adherence within its members, unlike, say, Catholics. Anecdotically, for example, almost everyone in Spain will self-identify as a catholic, but on a day to day basis many would be indistinguishable from self-identified atheists.

There are two ways one could define who is or who is not a Mormon: By self-identification, and by the observation of behaviour. It is almost an analytical truth that the latter is a subset of the former, assuming that there are not many mormon weeaboos who walk the walk but don't believe the belief. Thus, comparing both groups could give us an idea of the effects of sheer belief and the effects of the community aspects of religion.

Mormons live all over the world, and even though it is mostly associated to its birthplace, Utah, most mormons live outside of the US (according to LDS numbers). Within the US, a third are in Utah. By percentage of population, however, Utah (And to some extent, American Samoa and Idaho) is the state with the most mormons:55% of the population belongs to the LDS church. Outside of the US, in Tonga, self-declared LDS membership is 18% (2011), and Samoa slighly lower than Tonga.

However, one also has to consider effective, practicing mormonism, from passive (Just belief) mormonisn:More than half of LDS-Recognised mormons may not be religiously active.

Mormons and Americans

An initial starting point is to compare the lives of mormons within the US with the rest of Americans, and fellow Utahns.

As one might expect, mormons have traditional beliefs regarding marriage, religion, and family life (Though they are not immune to the relentless march of moral progress). Demographically, mormons are younger, and mostly (85%) white. In accordance with those beliefs, mormons marry more, have more kids, and tend to marry other mormons.

Regarding income, it does not seem that mormons are overrepresented among the wealthy, if anything they are somewhat underrepresented amongst the poor. If there are religions that excel those would be Judaism and Hinduism. They are not also particularly educated, compared with other groups. Interestingly, if one looks at degree of belief, the two successful religions are more likely to have members that are not that convinced about their God's existence,and even have many members who straight say that they don't believe in God, but still identify as part of that religion. Together with Jehovah's Witnesses, Mormons are the most engaged group: As many as 77% of them claim to attend religious services at least once a week. But contrary to JW's, mormons are the group most in favor of reducing the size of government, with many believing that government aid for the poor harms them.

So far, it does not look like an extremely remarkable group: As Razib Khan put it back in 2010, Mormons are average white folk.

He admits that their "floor" (% in poverty, or % with no more than a high school education) may be what leads to people's perception of them as an exemplar group, and it is true that this continues to be the case in the Pew data I've looked at for the previous paragraph. However, given the more white racial composition of the Mormon group, and that the poverty rate among whites is lower, one would have to correct for this.

Why that could be? Besides the religious values, the LDS Church has its own welfare system that runs on trust: a local community leader (bishop) is in charge of managing the congregation's "fast offerings", which can amount to a large sum, and has full authority to give away that money in any way the bishop sees fit, no strings attached and no bureaucracy involved. At least in Utah, the Church owns a massive charity operation.

There are a few studies I found that look at mormons in particular:

For delinquency I find an interesting first paper (Kelly et al, 2015), though they barely mentions the mormons in a paragraph:

Stark, Kent, and Doyle (1982) returned to the issue and suggested that these contradictory findings were likely the result of the moral (i.e., religious) makeup of the community being studied. The authors predicted religion would deter delinquency in moral communities, but there would be little or no effect of religiosity on individuals residing in secularized communities. The ‘‘moral communities’’ hypothesis provided an important theoretical framework for understanding why religion reduced delinquency in some studies, whereas other studies found religion had no significant impact on delinquency (Stark, 1996; Stark, Kent, & Doyle, 1982). For example, studies of delinquency in religious communities such as Mormon Wards in Utah and Idaho yielded an inverse relationship between religious commitment measures and delinquency (Albrecht et al., 1977). Conversely, communities reporting lower church membership rates such as Richmond, California, failed to generate the inverse relationship (Hirschi & Stark, 1969).

But it's an interesting paragraph: it adds one more variable that one has to pay attention to: Perhaps religion reduces crime in smaller communities (Where you would be stealing from someone you most likely know) but doesn't on larger ones.

Jarvis (1977)studied mormon mortality rates in Canada, comparing them to the local non-LDS population, and found mortality rates lower across the board. This was also the case in King(1990) the study by that compared Utahn mormons vs non-mormons. A review around the same time Jarvis & Northcott (1987) mentions that every study done so far shows this mortality advantage for mormons, including a study done on Maoris (!)

A study(Bacon, 1957) mentions in passing that indeed there are few drinkers among the mormon, but those who are drinkers, drink much more compared to non-mormons- a finding replicated decades later (Michalak et al., 2007) and in California too Mormons were found to have lower mortality rates (Enstrom & Breslow, 2008).

One might think that this advantage in mortality rates is just from tobacco abstinence, or perhaps alcohol abstinence. Some of the works cited do mention that Mormons have even lower mortality rates than one might expect just from non-smoking, or that they have lower cancer mortality from cancer in sites that don't seem to be associated with smoking (e.g. colon cancer). However more recent work does point to smoking also being a causal factor involved in those types of cancer as well (Parkin, 2010).

All that said, how relevant is all this going forward? Tobacco smoking rates have plummeted. But there may be still health benefits from just religious participation. The Park paper above claimed that this relation -because there is one- is not a causal one, while Gruber said that there is, but he studied income and drug use, not health.

So far as health goes, the literature clearly points out to a Mormon advantage, with no doubt, with abstinence from tobacco -and I assume- alcohol as causal factors, plus maybe religious participation as such. I won't look deeper into religious participation here, as this is a topic that should be studied considering all religious participation, not just mormons.

It may also be worth looking at higher level data, because some trends may be hard to see at the individual level.

So at this point, I ran some models (OLS and GBM) to try to find county-level associations between mormonism and poverty and drug and alcohol related mortality mortality due to alcohol poisoning (controlling for income, race, and share of adherents of other religions), plus suicides. More on that later.

There's some evidence of this: Utah ranks seventh in the US in deaths from alcohol poisoning deaths, even though the binge drinking rate is 6 percentage points lower than the average of the US. The suicide rate was the fifth highest (in 2008) in the US. Other Mormon-heavy states like Idaho or Wyoming also rank high in the latter metric. Wyoming (2nd) and Utah (5th) are also high in adolescent suicide. Utah also has a high rate of opioid addiction. Why could this be? It can be, of course, that the rates of death are lower for mormons in these states, and higher for the non-mormons, thus being non-mormon in a mormon area might turn out to be really bad for you! We don't know. These statistics are aggregated. It can be that, as pointed out in the Guardian article, the LDS Church impositions on their members:

“The LDS church is a big part of it. I go to church every week and I see where the challenge is. They make people feel that they should be perfect and they feel inferior, like they can’t live up to the standards of what they expect them to live up to. So they start using prescription painkillers not to address pain, physical pain, but the mental issues that go along with feeling inferior. That you just cannot cope with all the things you’re expected to be and to do.”

These statistics, when contrasted with the individual-level data, seem paradoxical. I am not the first one noting this, of course,

Utah is the happiest state in America.

They have the lowest divorce rate, the highest job satisfaction, lowest median work hours, highest rate of volunteerism. It is immensely healthy - low smoking rates, clean drinking water, and massively beautiful national parks tempting the population to spend time outside. Even Utah's online presence is cheerfully sanguine. A recent Twitter study shows that Utahns tend to use words like "rainbow," "wonderful," and "Christmas" enough to make you think it is a state full of Pollyannas.

But this is only half the picture. Somehow, while Utah is ranked by many measures as the happiest state, it is also ranked as the saddest.

Utah has higher rates of depression than any other state. Accordingly, it ranks #1 in the US in antidepressant drug use, at a rate twice the national average. In fact, Utah has the highest rates of mental illness as a whole, with nearly 1 in 4 residents experiencing a mental disorder within the last year. They are

#1 in bankruptcy filings,#1 in pornography consumption,and, most tragically, ~~#1 in child sexual abuse, d~~espite widespread under-reporting. Under-reporting is also a problem in cases of suicide, which is the most common cause of death for young men in Utah between 11-17 years old. Among the 50 states, Utah claims the #4 highest suicide rate. (The Utah Paradox)

EDIT [01-12-19] Utah ranks as first in the paper they cite, however Idaho, a state with the second highest number of LDS members, ranks at the bottom. Also, it is not the case as measured by a certain popular pornography site. Utah is also number 4, not 1 in brankrupcy filings these days. For child sex abuse, this is not true either.

I have to remark that the situation reminds me of what happens with Nordic countries. Are Mormons cryptonordics? But it need not be Mormonism. Some people have proposed that the higher suicide rates in those areas is due to their higher altitude (Ha & Tu, 2018). Utah and the surrounding areas (what used to be the LDS-run State of Deseret) happen to be at high elevation. (it's not an isolated paper). Thus, one would have to add altitude as a control, because fixed-effects at a state level (What the first version of my models used) may be bunching together good effects from state-level mormonism (control over what laws get passed) with negative effects from state-level altitude.

Back to the models: I tried different things, OLS, OLS weighted by population, and boosted trees (using LightGBM), both trying to predict the relevant variable directly, and regressing the variable on income (a very strong predictor) and then working with the residual in the rest of the analysis. For poverty, I used two poverty metrics, one from the American Community Survey and another one from the Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates progam. Results were similar in both. In the final models, the variables controlled for are income, population, percentage of [non-hispanic whites, blacks, asians, hispanics, native americans], % of mormons in the state, altitude of the county, state-level fixed effects, and % mormon. This is all at a county level, so nothing can be said about individuals..

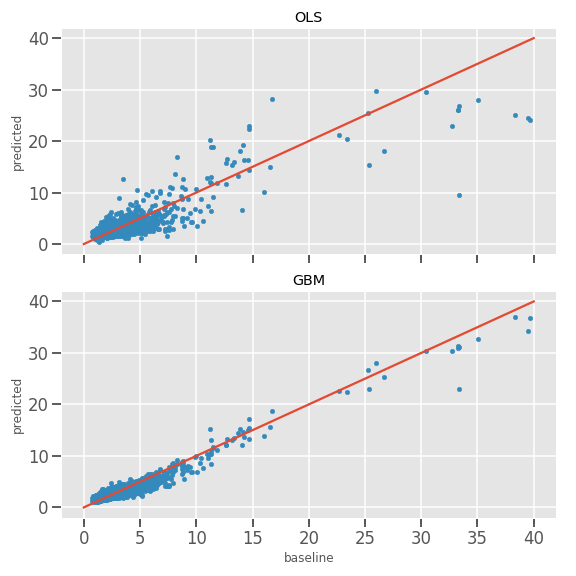

You can find details about these models in the OpenNintil repo. In case of doubt, the GBM is to be trusted more, as it more accurately predicts the underlying values. The plots below are, for example, what the prediction looks like for alcohol-poisoning-related mortality.

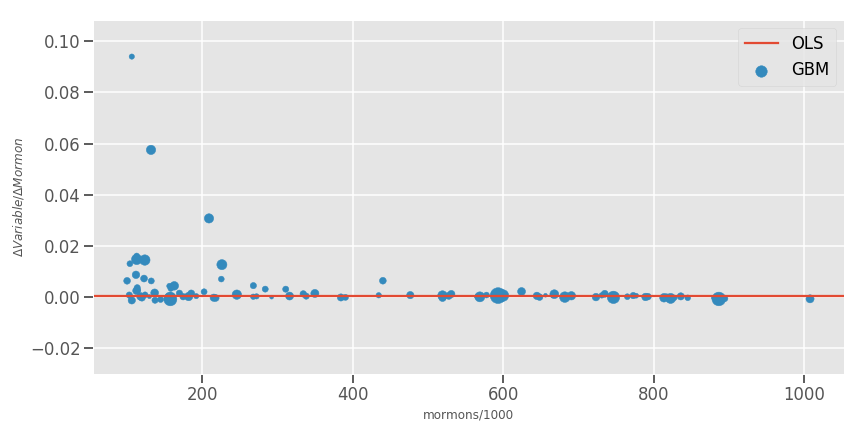

In this case (alcohol-poisoning-related mortality), the prediction for both models is roughly the same, I calculate a an elasticity for the variable of interest. For OLS, this is a single value, 3.76e-4. This means that if one fully converted an a mormon population (Where everyone is mormon) to atheism (let's call this 'the counterfactual'), one would expect a decrease in mortality attributable to alcohol poisoning by 0.375 points. The average rate is 2.97 per 100k population, so this is a negligible amount in the grand scheme of things, even when it is a 7% increase. Actually, the coefficient in the OLS model is not even statistically significant. (I've trimmed the plot below it at populations with only >10% mormons).

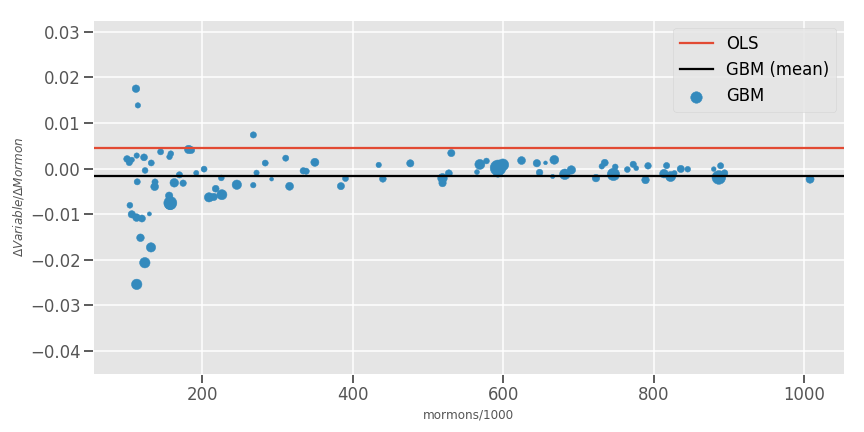

For mortality due to drug abuse, the models give different answers: OLS would predict a decrease of 4.42 points in the counterfactual (this time the coefficient is significant), while GBM predicts an increase of 1.62 points. The average rate is 9.07 per 1000:

An interesting factor that came out of feature importance analysis here was population: It trumped income as the most powerful predictor of mortality due to drugs. (For alcohol, population was a minor factor, while the % of native americans was the dominant factor)

Drug use also shows diverging estimates; OLS would predict a decrease in drug use of 4.4 points, and GBM, an increase of 1.6 points on average (baseline average is 9.07 so these effects are significant)

Suicide was another outcome of interest: In this case, the effects turn out to be negative in both cases: in the counterfactual, there is an decrease of 1.37 (OLS) / 7.8 (GBM) points, above a mean value of 16.21 per 100k.

In case of doubt, I go with the GBM model, and for the outcomes above we see that mormonism is weakly good for drug abuse, bad for suicides, and not significant for alcohol-poisoning-related deaths. This is not to say that, for example, mormonism has no other effects via alcohol, someone who is heavily drunk may be alive, and yet not being able to be productive.

[EDIT 01-12-19]: A paper I did not cite but that I should, using better data than what I was able to find, shows that there is a negative relation between LDS membership and suicide. Thus the result above for suicide is less likely to be true.

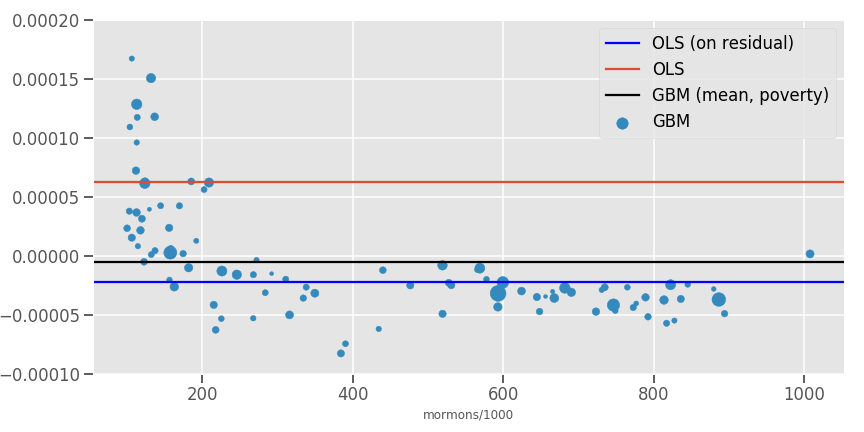

Poverty is strongly correlated with income, so here I decided to control for income first, and then model the residual with the rest of the variables. The GBM model is closer to the OLS model when fitted to the residual. In all cases coefficients are fairly small (but significant). The estimate here is that the OLS model would predict a decrease in poverty of 0.022 points, while GBM would predict a tenth of that. The baseline rate is 16.7%, so the effect is negligible. This is what the results plot look like:

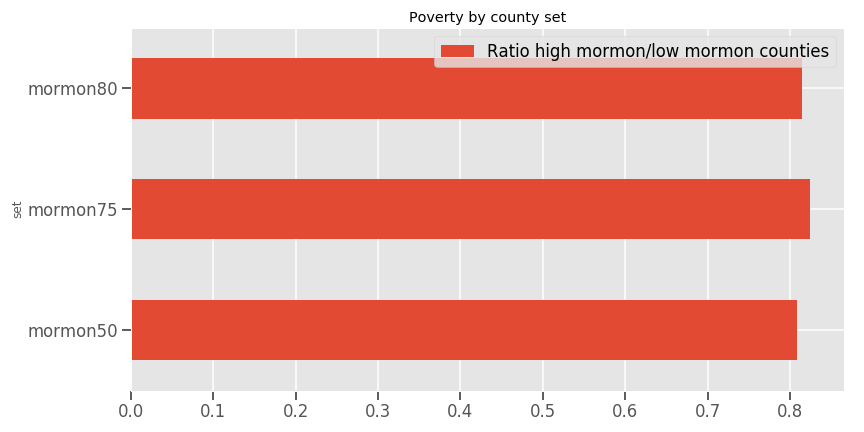

In other words, mormonism does not have an economically significant effect on poverty at a county level. I was expecting to see a stronger positive effect on poverty, but the data does not bear that out. To sanity-check the results above, I look at the data directly:

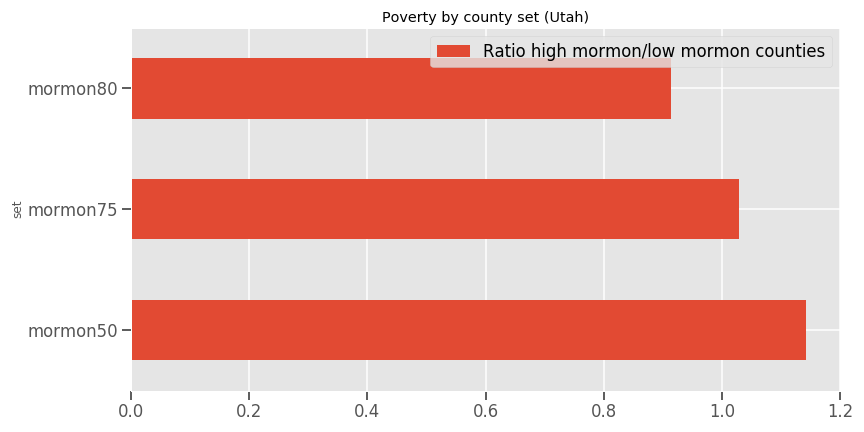

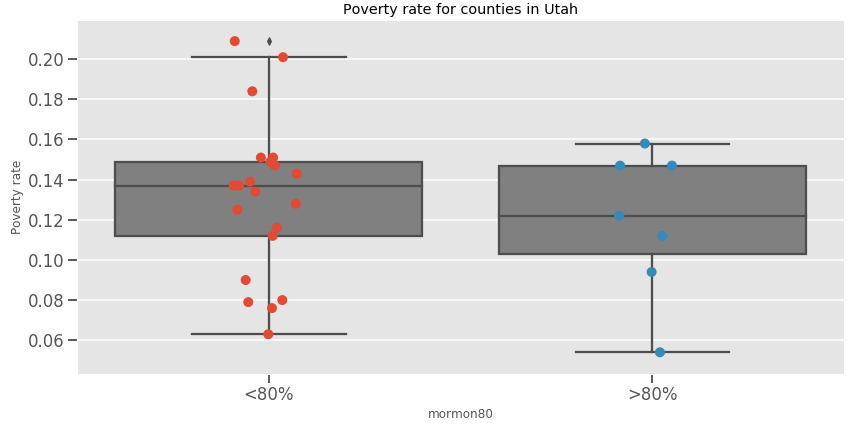

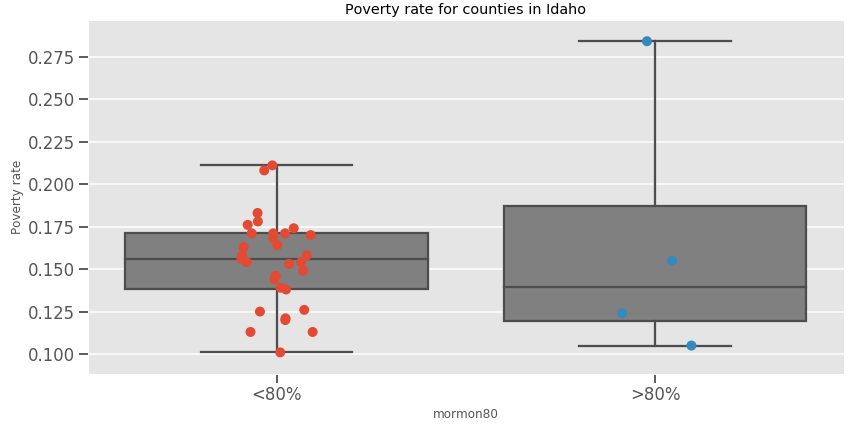

Here, mormon80 means that the bar represents the ratio between the mean of the poverty rate in counties where more than 80% of the population is mormon, and counties where les of 80% of the population is mormon. Thus, this would seem to show that a high rate of mormonism reduces poverty by 20%. But this obviates obvious confounders. If we look at just within, say, Utah, and limit ourselves to counties with more than 75% whites, this is what it would look like:

The sample sizes in the plot above are not big, just a few datapoints:

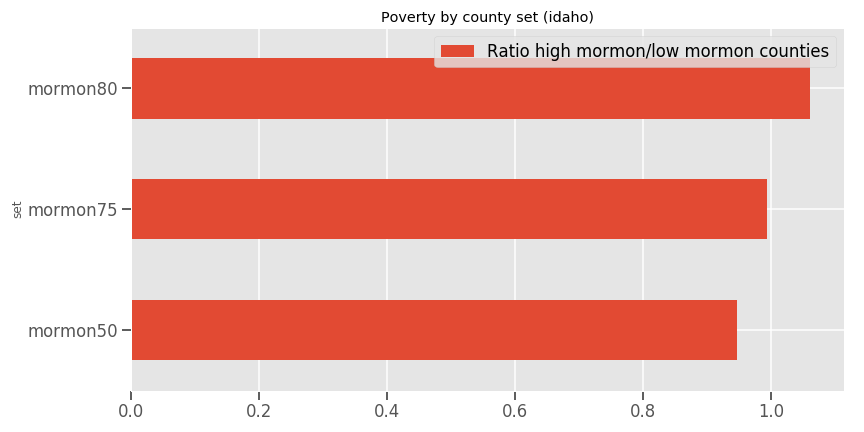

However, if we do the same for Idaho,

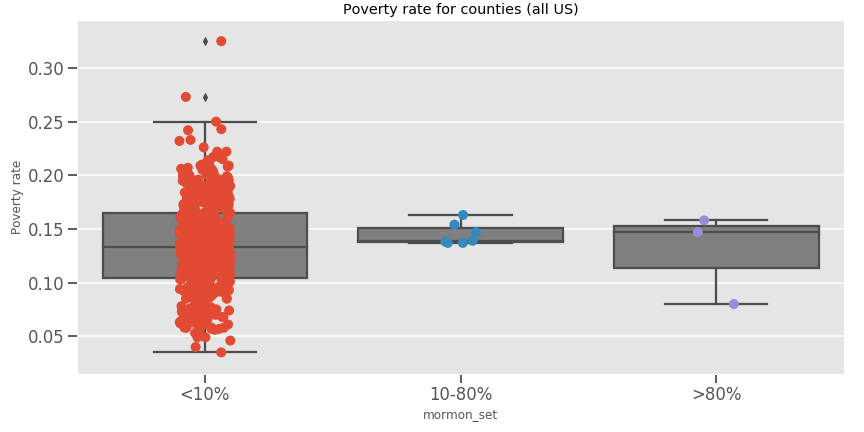

We get the opposite conclusion. This, together with the models, does suggest that strong claims about the effect of % mormons on poverty are not warranted at least just yet. Even when looking at the whole of the US (counties with > 75% whites, and income and population within +/- 20% of the values of Salt Lake City, we don't really find an effect:

Conclusion

In this post I have provided some evidence about religion in general and its effects on a range of outcomes. To me the most interesting bits are the RCT and the literature survey on economic growth. The RCT shows that, at least in that particular case, religious belief (separated from, say, health norms) can have a positive outcome (here, on income). [EDIT 2019-02-01: Although, as noted above, the effects fade out after two years]

As for mormonism, the main topic of this blogpost, the first thing to note is the difficulty in obtaining quality data. The clearest evidence is from some old studies about mortality: back then mormons are clearly healthier than their peers in locations inside and outside the US. Nowadays, it's less clear. The negative effects of tobacco are more obvious than those of alcohol. What alcohol consumption does would be a topic for a whole new post, as I recall there is conflicting evidence about its effects: while there is consensus that elevated consumption has negative consequences, for low doses I've seen evidence pointing to tiny negative, neutral, and slightly positive effects. From the Pew study, mormons tend to be somewhat less poor than non-mormons, albeit this is before controlling for confounders.

Looking at data at a county level, a different pattern becomes salient: First, from anecdotic evidence gathered online and then modeling the relations between a set of outcomes and mormonism and other variables, it seems that in the aggregate the effects of mormonism are mixed: For some reason it is correlated with an increase in mortality due to alcohol poisoning. The mechanism might be that there where there are strong social norms against alcohol, or some drug, a culture of safe consumption does not develop, and you end up with a skewed distribution of most people not consuming, and a few binging. Looking at other countries, it isnot clear that there is an association between an alcohol-positive culture and more deaths from alcohol-related disorders.

I wouldn't recommend conversion to a strict religion as an anti-poverty measure, and I wouldn't even recommend, at this stage at least, complete alcohol abstinence (And I say this as someone who rarely drinks*!) unless one has, or is expected to have, problems with alcohol. More research is needed, and the best evidence here will be in the form of more RCTs, or twin studies; it could even be that existing twin studies have measured religion, and thus it may be possible to isolate its effect without the need for new sample gathering.

Ideally, now someone will take my dataset and my notebooks and try something different, hopefully enhancing it with more data. Please do tell me if you find different results!

Caveats and limitations

- The size of the dataset should imply enough statistical power to detect "big" effect, but subtler ones may not have been captured.

- I may have failed to control for other major covariates of the relevant variables

- The analysis is limited to the US.

- The "mormon" variable, as noted in the OpenNintil notes, is known to be biased upwards. But if this bias is constant, it shouldn't affect the analysis much.

- There may be effects at a community level that are not present at a county level; my analysis cannot capture those.

- Similarly, there may be odd interaction effects at play between the mormon and non-mormon subsets of the population that I can't capture

- A step up from this analysis would be doing Structural Equation Modeling (e.g. using lavaan)

- Better feature engineering may have led to better estimates of the OLS coefficients. I backed the results up with GBM because they do not require as much data formatting as OLS.

- This is mostly an exploration of developed countries, and modern times. So this does not apply to tribes or smaller scale societies.

Comments from WordPress

-

Monday assorted links - Marginal REVOLUTION 2019-01-07T18:10:10Z

[…] On the causal powers of Mormonism. Highly […]

-

Rational Feed – deluks917 2019-01-06T01:34:56Z

[…] On The Causal Powers Of Mormonism by Artir – Artir’s analyses some the data on religion (in particular Mormonism) and poverty and comes to a skeptical conclusion. He does not recommend religion as an anti-poverty measure. […]

-

Power of Mormonism | Leadingchurch.com 2019-01-12T00:24:46Z

[…] https://nintil.com/2019/01/05/on-the-causal-powers-of-mormonism […]

-

Links for the Week of January 7th, 2019 – Verywhen 2019-01-07T04:14:31Z

[…] On the causal powers of Mormonism | Nintil […]

-

Kevin Black 2019-01-06T05:03:23Z

Nice work. Two points of fact.

- LDS welfare is not quite as you describe (e.g., bishops never have control over tithing, which dues not stay with the local congregation), though for this purpose your summary is likely to have a similar effect to the actual system.

- There is data on the suicide question in LDS vs. non-LDS Utahns. See https://works.bepress.com/kjb/27/ for an admittedly partisan summary of an early report; the authors of the epidemiological work cited there later published a more direct comparison with similar conclusion to my letter's, but I don't have that citation at hand.

-

Trey 2019-01-07T23:24:31Z

I would highly recommend conversion for everybody. Since joining the Church of Jesus Christ, of Latter-day Saints 18 months ago, my life has gotten happier and happier.

The negatives reported here correspond to what I see as less than faithful adherents living around faithful adherents and noting the stark contrast in outcomes.

The big Y on the mountainsid behind BYU in Provo is a graphic of this point. As individuals follow the true Way of Jesus Christ, their lives go strongly in one positive direction, while those who aware of the true Way and do oot follow it see their lives go in another direction.

This does not mean that both groups do not face tough circumstances. I write today at my wife's emergency room bed side. We know though, through, with, and in Jesus Christ, all things work for good, even emergency room visits.

Citation

In academic work, please cite this essay as:

Ricón, José Luis, “On the causal powers of Mormonism [revised]”, Nintil (2019-01-05), available at https://nintil.com/on-the-causal-powers-of-mormonism/.

Comments