No Great Technological Stagnation

Many economists say we are living through a Great Stagnation. The term, was made famous by Tyler Cowen'sbook of the same name and the latest iteration is, of course, Robert Gordon's The Rise and Fall of American Growth.

But they usually look at economic factors like Total Factor Productivity (TFP) or GDP per hour worked. By these measures, we are living through a stagnant period. Some expected that the stagnation would go away once we properly accounted for the Internet and similar hard to account for innovations, but apparently this was done, and the picture doesn't change much.

In this post, I take an engineering perspective and look directly at technology itself. I think this approach has not been sufficiently explored: We should look at quantifiable changes in technology over time, across the board. Surely productivity is important, but since technology is supposed to be a substantial component of TFP, why not look at it directly?

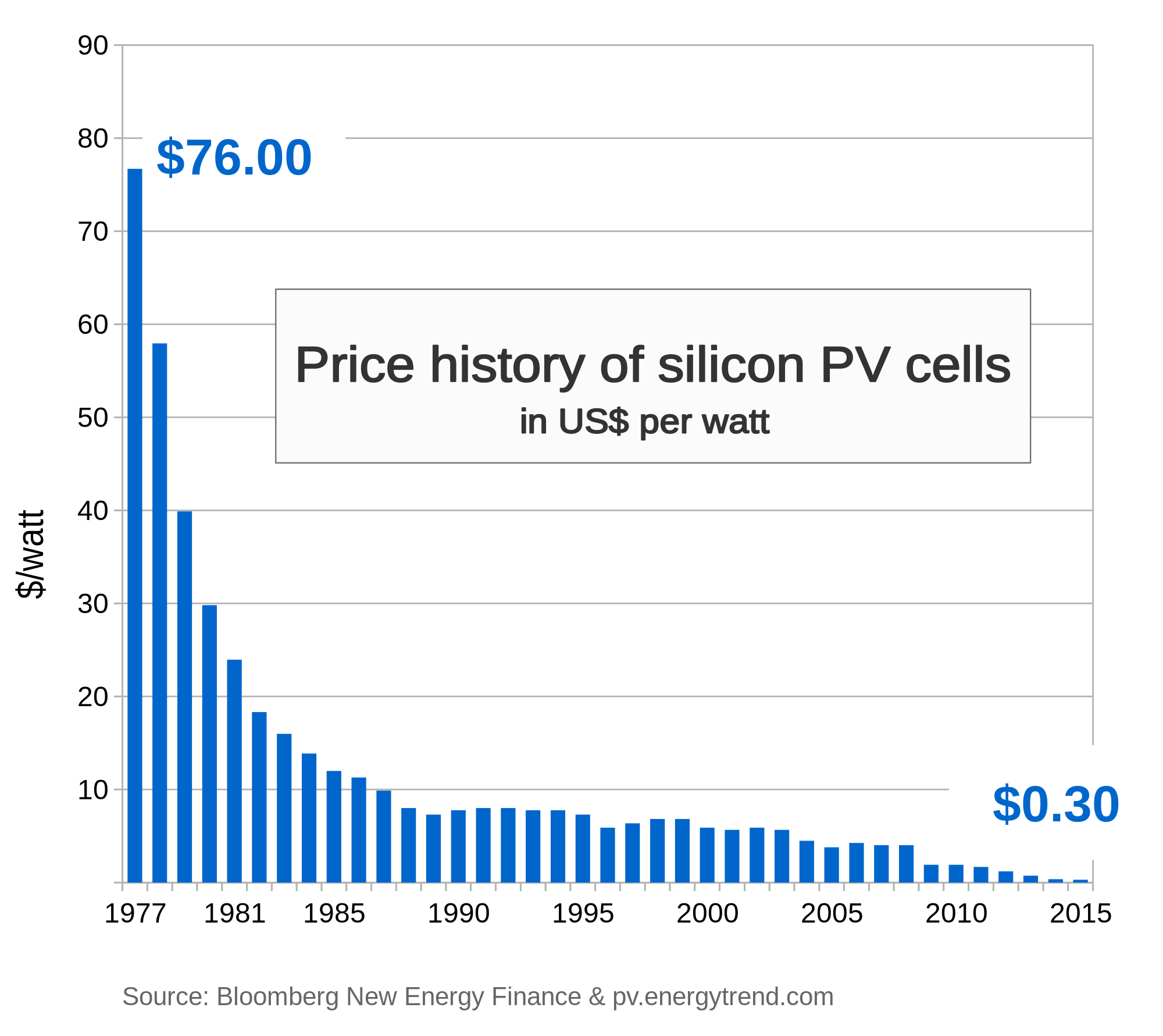

My point here is that, by the measures we have, there is no great technological stagnation (But this is compatible with a slowdown in economic growth). What we do have is stagnation in some sectors (Aircraft speed), improvements in others (Gene editing, photovoltaics), and worsening in a few (Cost per new drug approved). Furthermore, these trends don't seem to change radically in 1970, which is when the economic stagnation seemingly begins. What we have are a series of drivers -to be explored in later posts - that individually influence where these technologies go. Thus I think it is important to look at them individually rather than aggregate them as one would from an economic lens and say that everything is stagnating, because that's clearly not the case, even if we take software out of the equation.

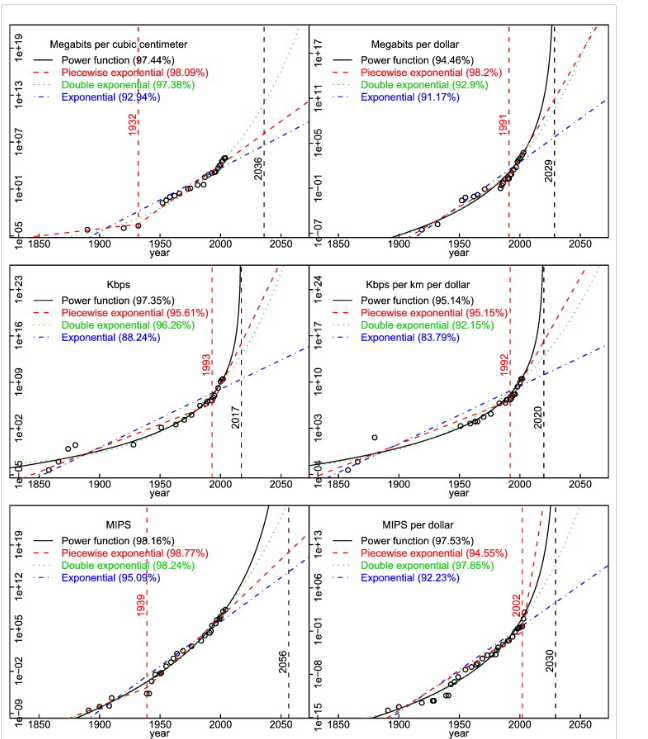

Let's begin with some charts. Here (Nagy et al. 2011), you have long run trends for several Information Technologies and different curve fittings for them. In the paper they explain which one is the best one. Hint: not the exponential!

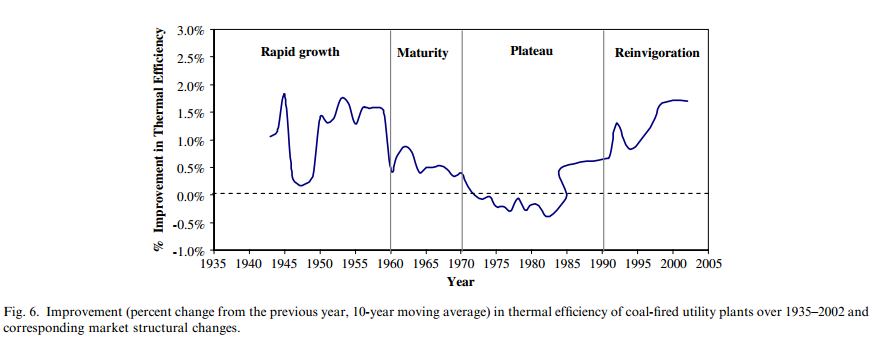

However, if you happen to be into pulverized coal-fired utility boilers, I also have a paper for you, Yeh & Rubin (2007)

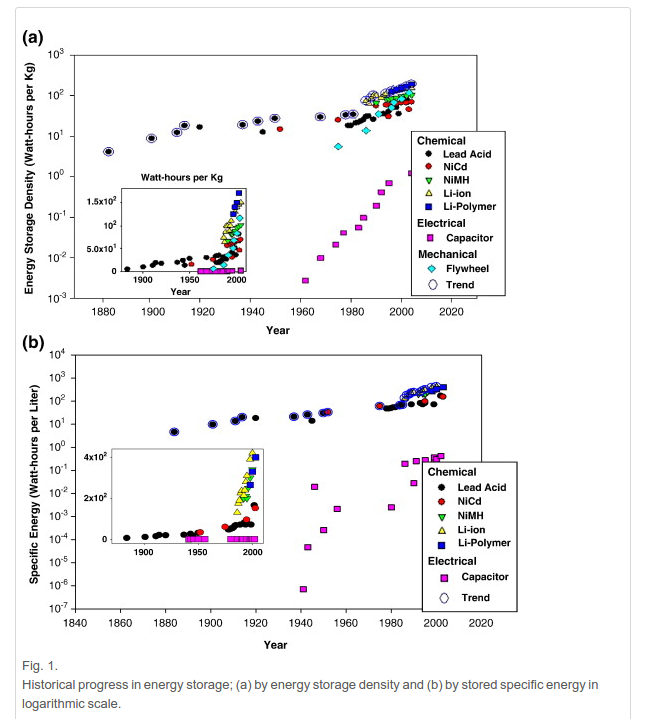

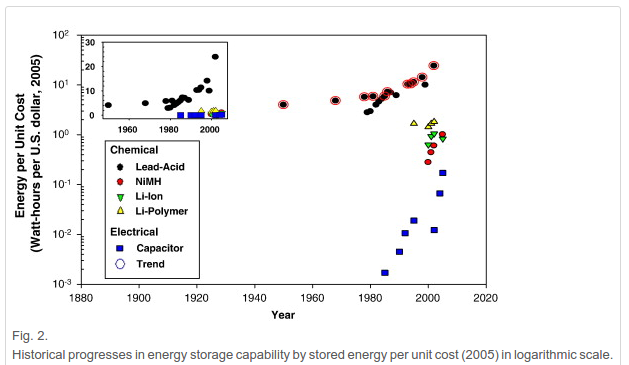

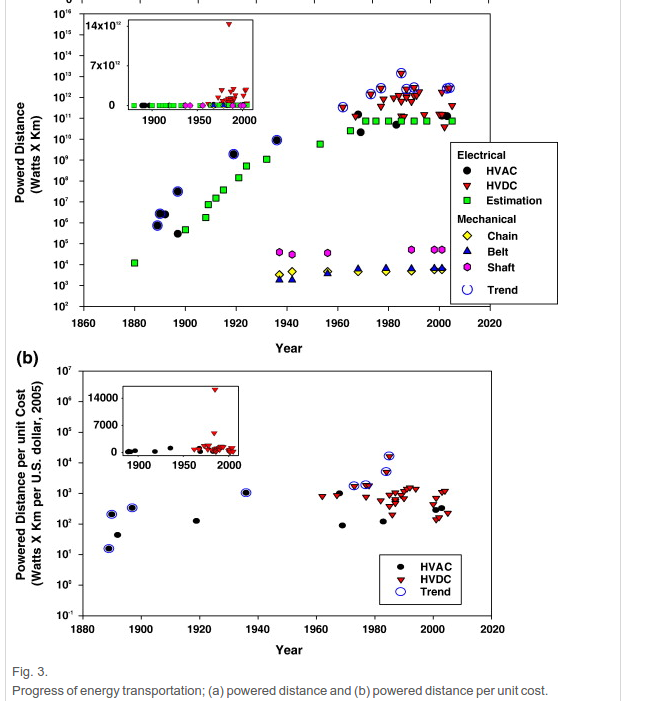

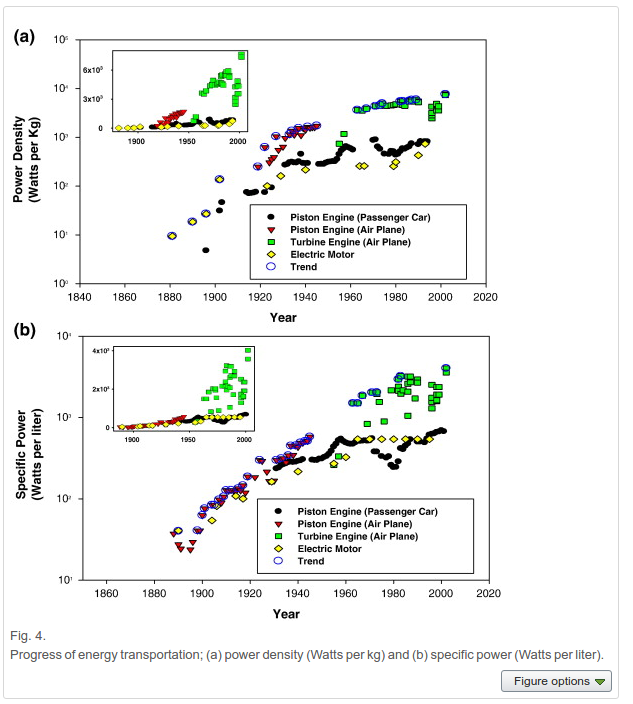

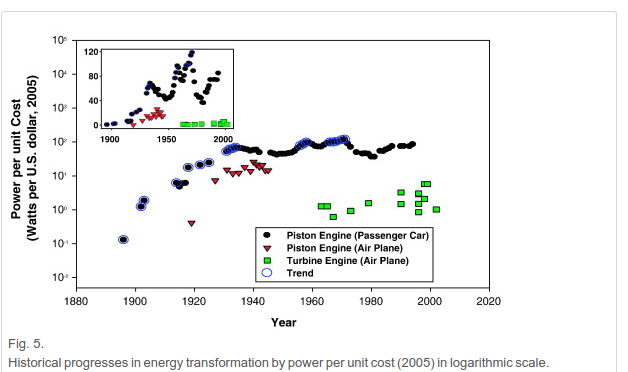

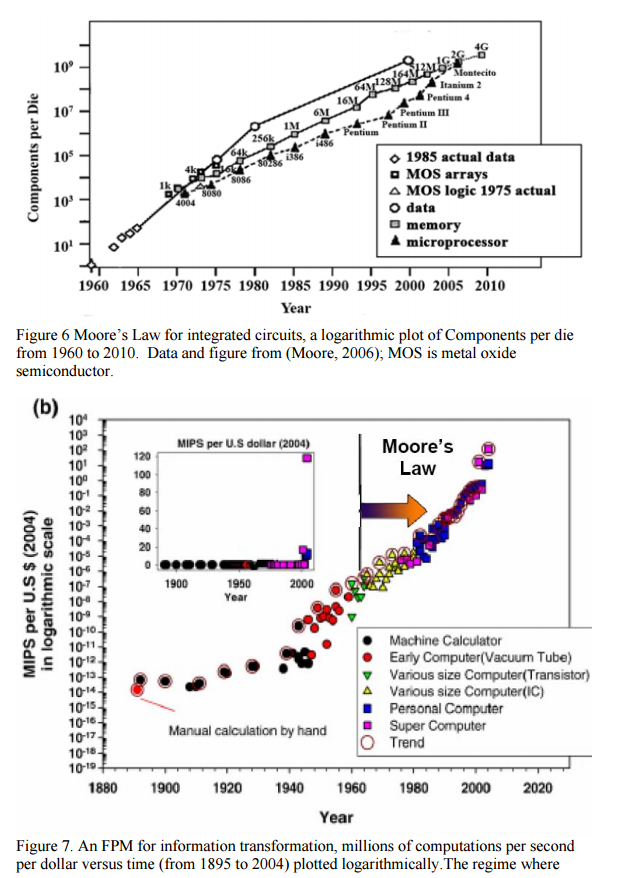

And what about energy technology more broadly? Yes, there are also papers for that. Koh & Magee (2008).

And what about energy technology more broadly? Yes, there are also papers for that. Koh & Magee (2008).

Some of these trends are plateauing. But there is no slowdown from the 70s.

And they even go on to say that

The consistency of the rates of progress in the different functional categories over time might make us hesitate in accepting theories that hypothesize clear breaks in technological eras associated with different kinds of operands. The continuous nature of the progress rate improvements over many decades in both energy and information technology appears inconsistent with the idea of distinct revolutionary periods for either or both types of technologies.

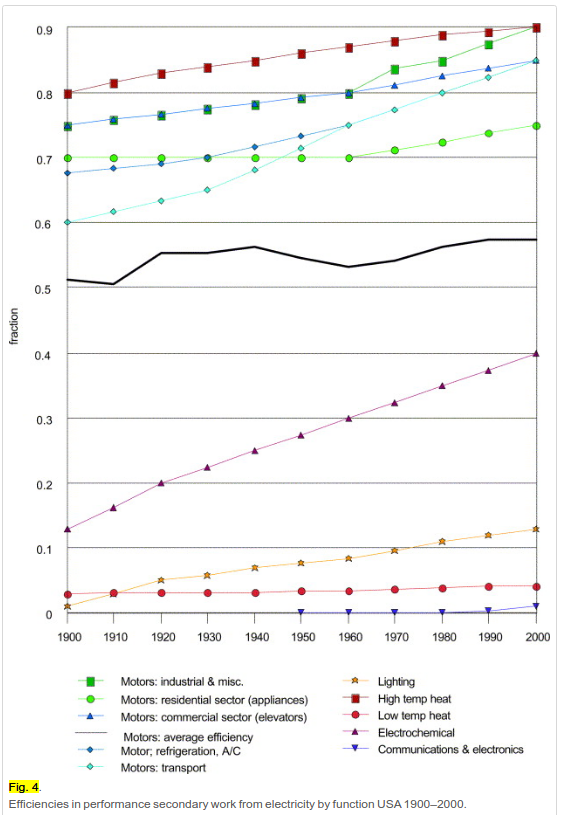

I also have plots for energy efficiency from Ayres et al. (2005)

High temp heat are electric furnaces, low temp heat is heating, electronics is radio, TV and information processing (transmitting waves wastes energy). Average efficiency stays like that because the mix of appliances has changed, not because technological efficiency hasn't, says Ayres.

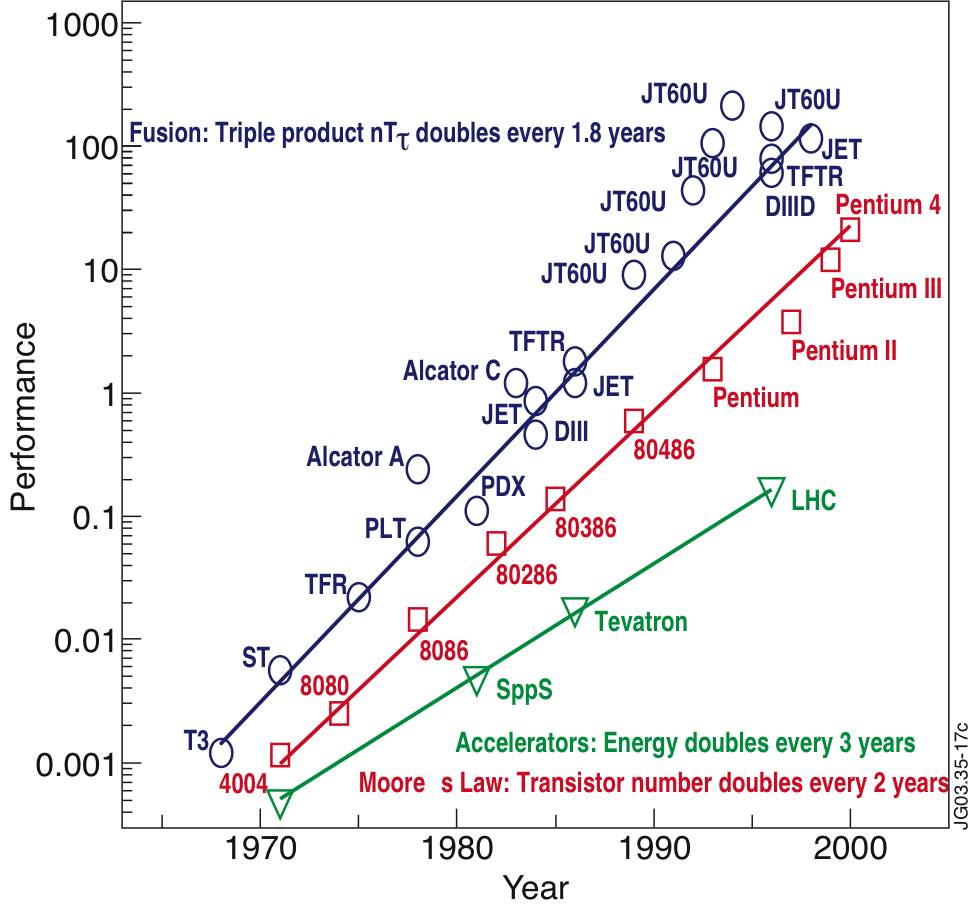

Next, Moore's Law, just because if you write about technological progress without mentioning Moore's Law, Ray Kurzweil might get angry or something. From Magee (2012)

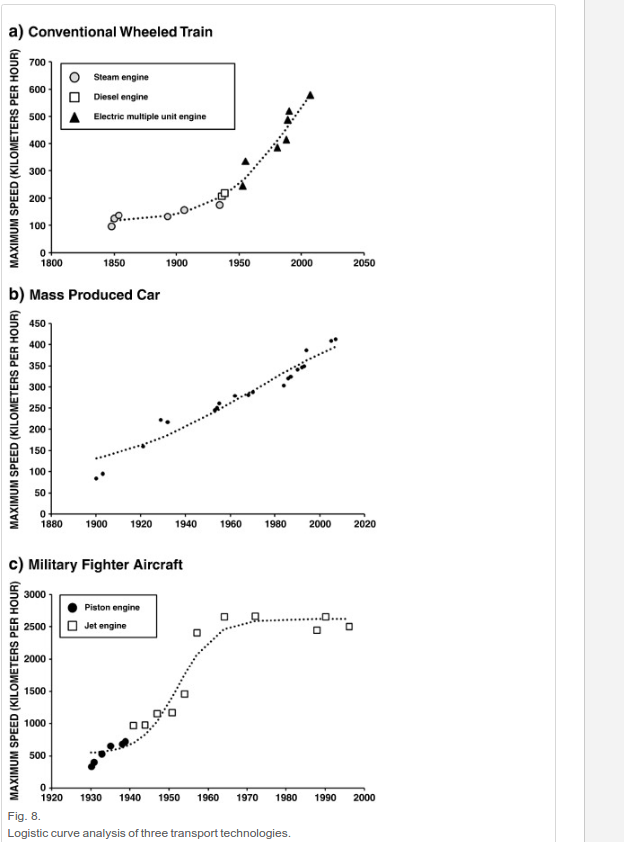

Speed for some transports, from Chang & Baek (2010)

There seems to be a great stagnation in military aircraft speed(!). But not in trains or automobiles.

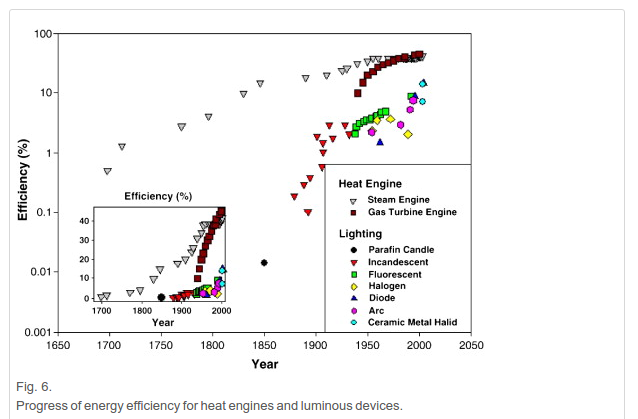

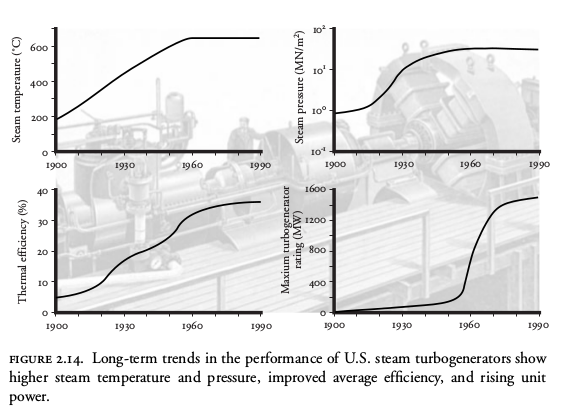

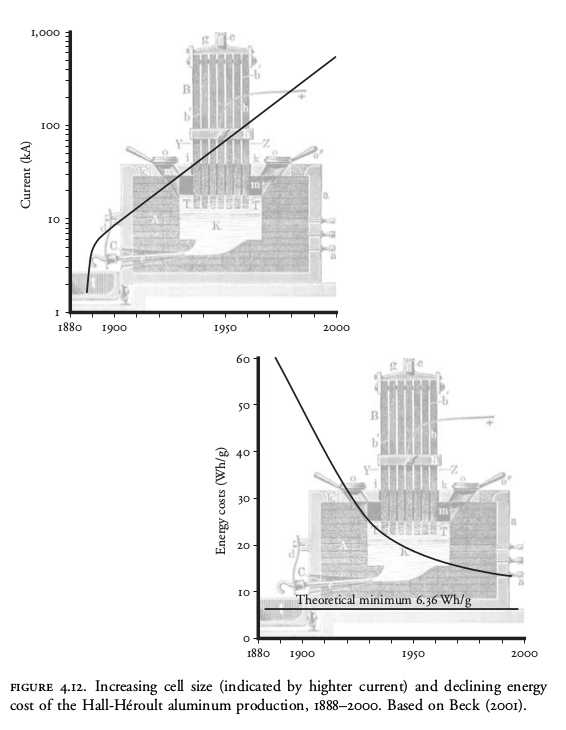

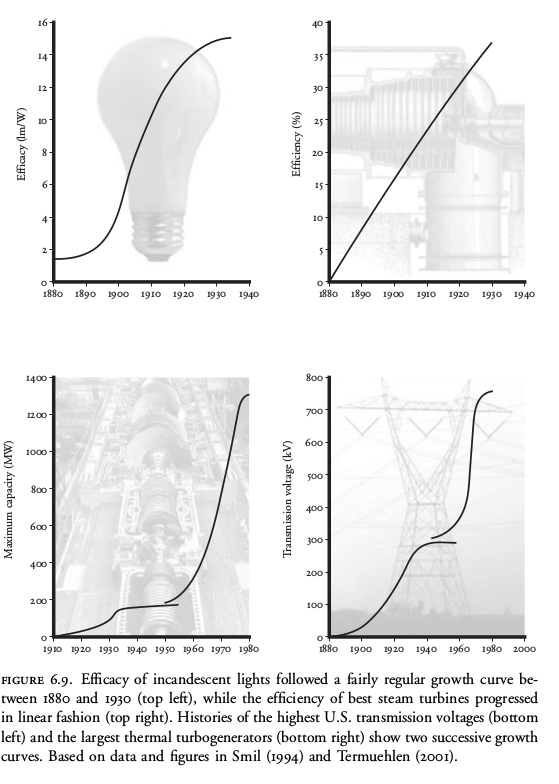

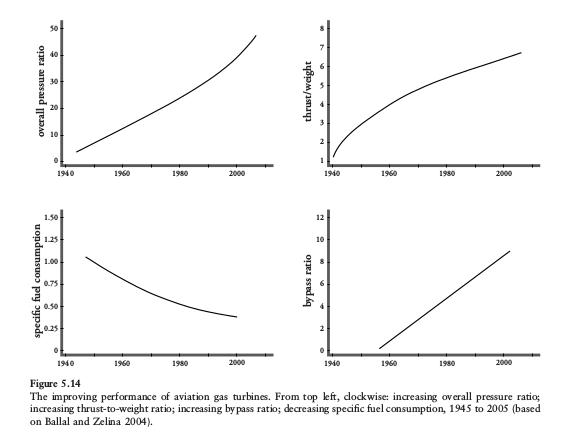

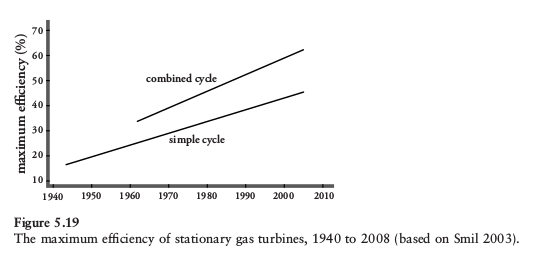

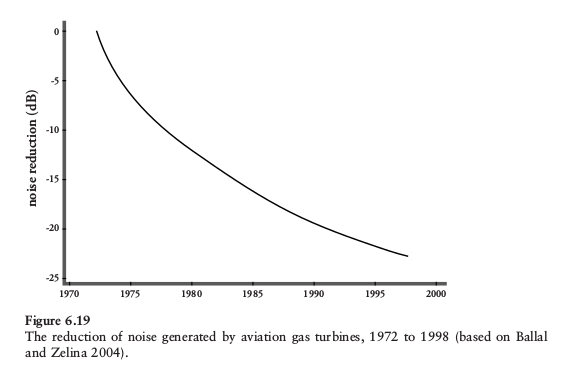

Now, some from Smil (2005)

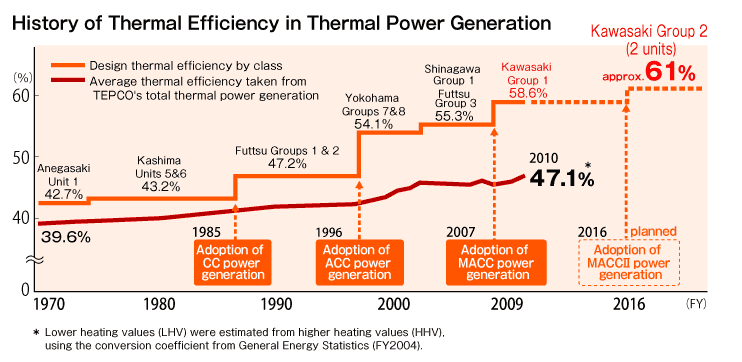

Okay, there is some thermal efficiency stagnation, but it may have recovered after the 90s. Data from TEPCO, later shows increasing improvements. It could be interesting to study just this technology to see what is really going on.

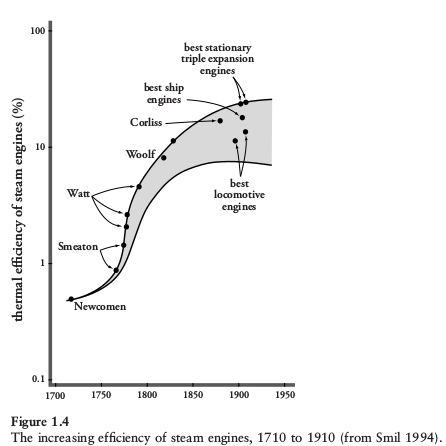

From Smil (2010) now, and dedicated to Anton Howes, steam engines!:

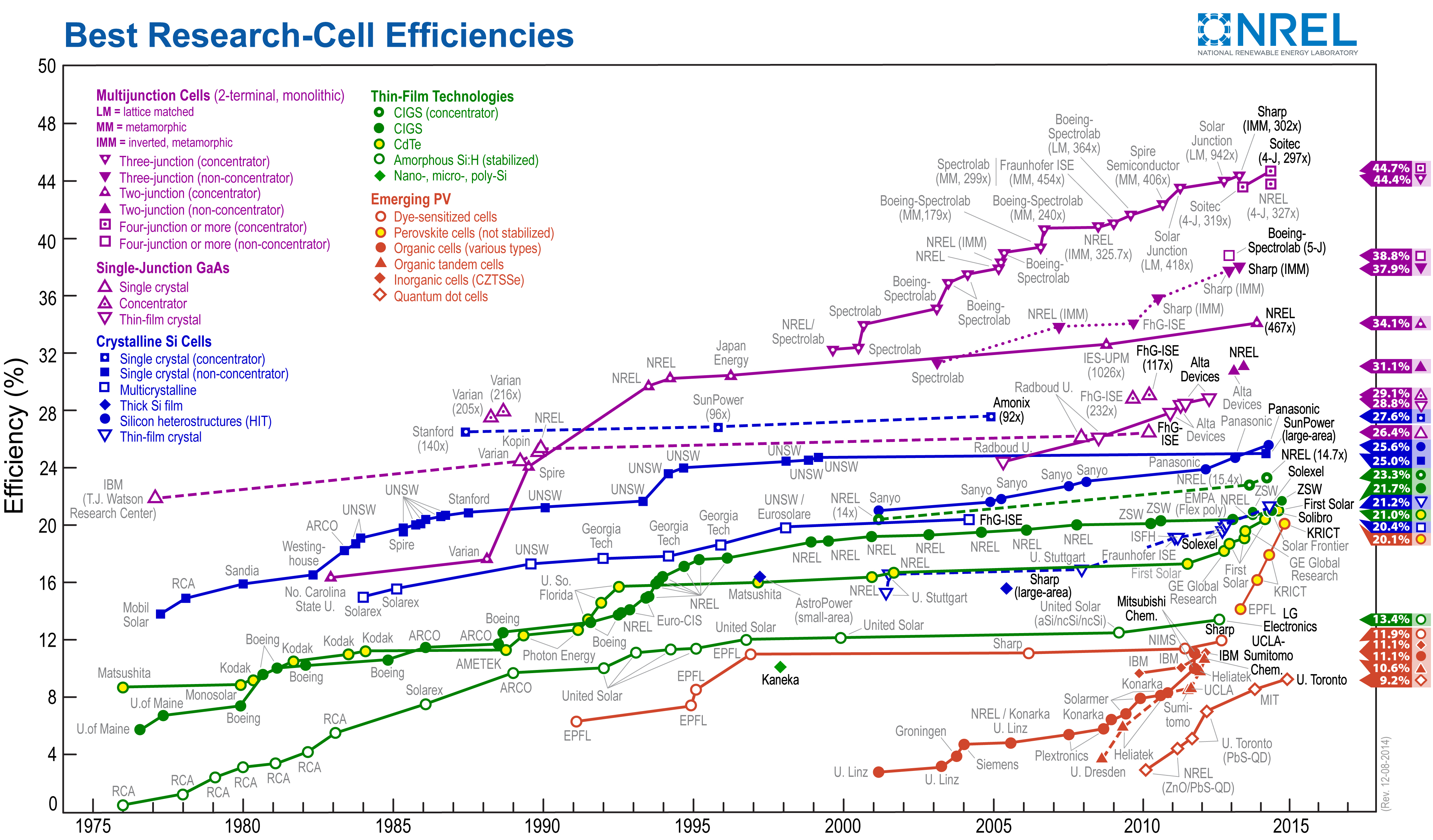

Solar panel efficiency, from NREL's famous chart

Thermal efficiency forTEPCO power stations

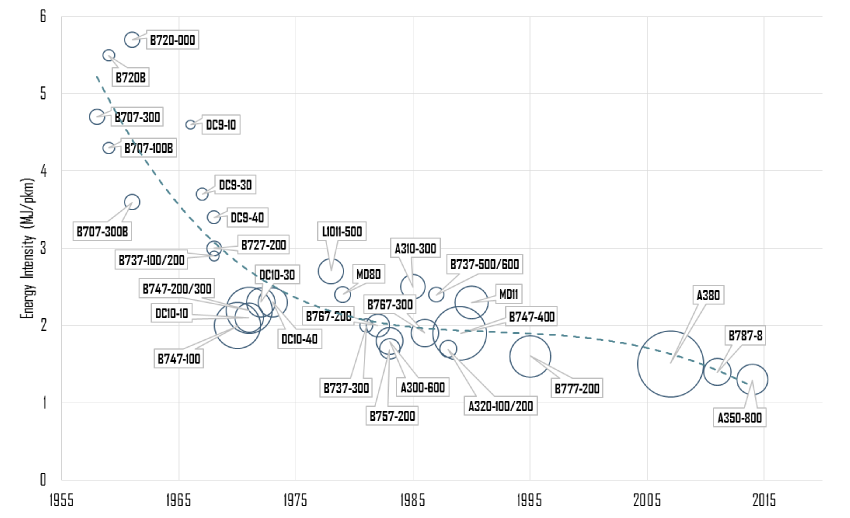

Aircraft fuel efficiency from here and here (The units in the first chart seem to be gallons per seat-hour, not gallons per seat-mile)

[gallery ids="3659" type="rectangular"]

Fusion energy (a figure of merit)

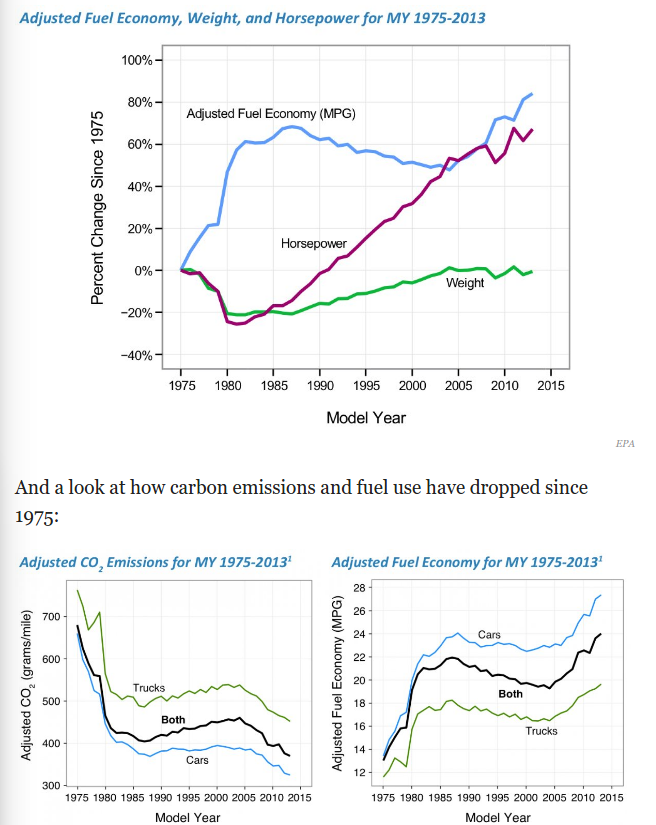

And automobile fuel efficiency and emissions from here

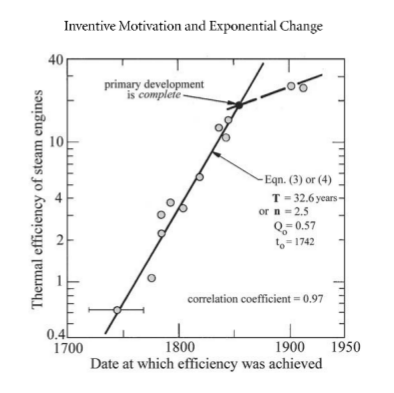

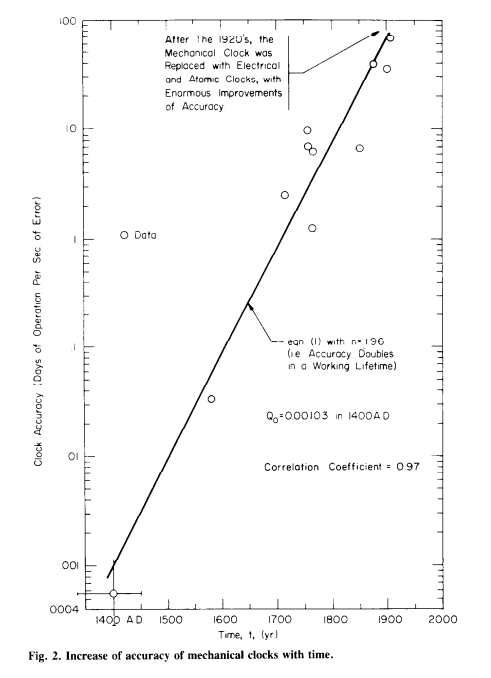

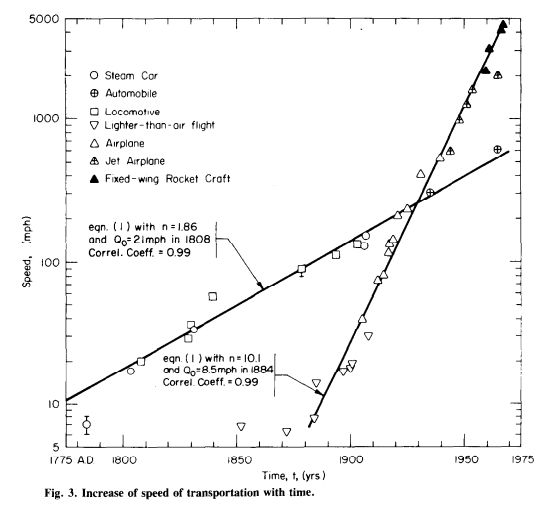

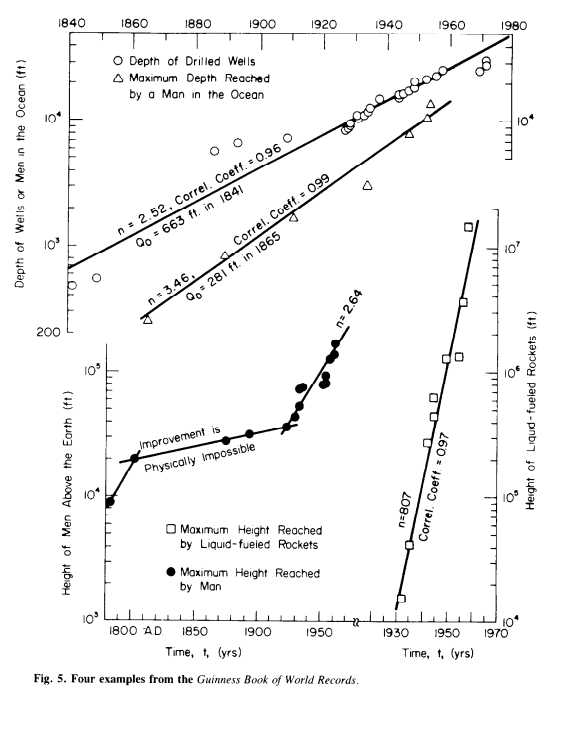

To finish, some plots from Lienhard (2006)and Lienhard (1985). Not all of them are post 1970, but they are interesting nonetheless

So there is no great technological stagnation across the board everywhere, at least in these technologies. From available timeseries one cannot see it. For a given technology, progress tends to follow a constant law until it's not possible anymore for it to progress, in which case a switch to a different technology happens.

Even for breakthrough innovation, harder to measure, I would say that it has not slowed down, even when some argue the rate of innovation per capita has declined (But population has grown, so it's not that bad). And even if that's true, it didn't began in 1970, but in 1905, so it's not obvious that it would be the cause of the post-70s great stagnation.

I do not say Robert Gordon is wrong in general. Please read this postfor reasons why you can have growth in individual technologies and productivity slowdown in general.

Further Questions

- Are there less 'really innovative' innovations (Huebner's argument)? (h/t Ben Southwood)

- Is there stagnation in technologies related to the service sector? (h/t Austan Goolsbee)

- Absolute technological progress vs per monetary unit technological progress.

- Eroom's Law, aircraft SPEED stagnation, and other trends

Comments from WordPress

- Wednesday assorted links - Marginal REVOLUTION 2016-04-27T16:25:12Z

[…] When it comes to the great stagnation, don’t blame the engineers. A very good post with lots of detail; I say fear the […]

John Hall 2016-04-27T16:43:31Z

Economists typically measure innovation (TFP) as a residual of a regression instead of doing what you're doing. Perhaps they should do more of this.

Artir 2016-04-27T16:50:53Z

Yes. However, my approach doesn't tell whether all this technology is being transformed in growth. I personally like technology and science for the sake of it, but for many people it only matters if it is useful to them. Here Dietz Vollrath attempts to get the technological component out of TFP https://growthecon.com/blog/Gordon-TFP/ . But in the end it really depends on the assumptions that went into the growth model. I think that TFP is highly driven by complementarities in capital goods (i.e. K is not homogeneous. Building roads make cars more useful, and viceversa)

I did this just to rule out one possible explanation for stagnation. If there are no remaining explanations, perhaps the framework that outputs 'stagnation' as a result ought to be abandoned, but I think we can't do that yet.

Mongo 2016-04-27T17:54:58Z

TFP is defined as the residual of that GDP input function. Economists measure innovation in many different ways. And they don't equal TFP to innovation. And they don't pay too much attention to technological innovation if that does not reflect in consumer utility, reflected in prices and hard to measure otherwise.

Pittsburgh Mike 2016-05-24T14:28:34Z

There's something seriously wrong with your jet efficiency numbers in gallons/seat-mile numbers. A 747 burns about 5 gallons to go a mile, and holds between 300-500 people, depending upon lots of stuff. But even at 300 passengers, the 747's g/sm figure is 5/300 = .016. Your table shows that modern jets burn 2 gallons/seat-mile, and there's no way that's correct.

Artir 2016-05-26T10:54:47Z

I know. That chart is actually gallons per seat-hour, as I mention above the chart.

- Don Quijones: Wrath of Draghi Hits Germans Who Refuse to Blow Their Savings | naked capitalism 2016-05-06T08:50:17Z

[…] that notion, but it’s bunk. We’ve linked before to this lengthy and important post, No Great Technological Stagnation, and I encourage you to circulate it widely, particularly to […]

- Links for May 2016 | Cavalcade of Mammals 2016-05-24T17:23:21Z

[…] Review by Theda Skocpol of Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right by Jane Mayer Kevin Hall’s followup studies of the “Biggest Loser” dieters at +6 years, PDF Why the Gold Standard is poor policy List of Email to SMS Gateways Technological Improvement Graphs […]

J Oliver 2016-04-27T18:18:49Z

Gene examination and GMO technology is beginning to accelerate food growing improvements. There was a story about driving the 100 or so species of mosquito that bite humans to extinction. http://thewire.in/2016/02/03/flirting-with-the-ultimate-swat-20701/ That would be a huge plus for humanity.

Mark Pontin 2016-04-28T18:12:08Z

You're right. That you call it GMO indicates, though, that you're still thinking in terms of your dad's genetic engineering. Synthetic biology with CRISPR and next-gen DNA synthesis is to that stuff as the transistor was to the vacuum tube.

I've been hanging around with the synthetic bio crowd -- I work as a reporter part-time -- and most people, whether Robert Gordon or even the average engineer, have less conception than the proverbial buggy-manufacturer did in 1880 regarding what's going to hit global society over the coming decades.

David Milovich 2016-04-27T20:15:41Z

I think the minority of X-per-dollar graphs (inflation adjusted, I presume) speak much more directly to the question of the technological component of TFP stagnation than your other graphs. For example, a very expensive new car with a huge energy efficiency advantage may be an economically inefficient way to drive to work. As K and L grow, a lot the new tech our engineers make is, unsurprisingly, more advanced but also more costly to design, produce, and use. Tyler Cowen has made a similar point with all his "there is no great stagnation" links to frivolous innovations.

Even X-per-dollar doesn't tell the whole story since there may be diminishing returns to having more X.

name 2016-04-27T20:29:09Z

Just a note to let you know that your encryption doesn't work with older browsers.

- Links 4/28/16 | naked capitalism 2016-04-28T11:01:50Z

[…] No Great Technological Stagnation Nintil (resilc) […]

- 1 – No Great Technological Stagnation 2016-04-28T18:00:32Z

[…] Source:https://artir.wordpress.com/2016/04/25/no-great-technological-stagnation/ […]

Eric 2016-04-29T10:37:37Z

Very nice post Artir and lots of great data and charts. If you haven't seen it you might be interested in a recent paper from my Oxford colleagues: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048733315001699

Artir 2016-04-29T11:07:15Z

Yes, I have seen it, it's very interesting. That paper would deserve an entire post devoted to it. Here I tried to offer just a sketch rather an coherent story for simplicity.

- Weekend Reading CXXXIX : Blogcoven 2016-04-29T12:33:01Z

[…] https://artir.wordpress.com/2016/04/25/no-great-technological-stagnation/ […]

GregvP 2016-05-01T00:00:20Z

The stagnation that Gordon talks about is in economic growth from innovation, in the radical sense of economic: the flow of goods and services to households. (Cowen is a less precise thinker.)

Many people have made the same points you have, but there are some other perspectives on the reducing impact of innovation that I have seen only rarely or not at all. Two of them might be called the "ecological" argument and the dispersive discovery model.

Different innovations have different impacts, a point made repeatedly by Smil and others. The high-impact, pervasive innovations are rare, while the bulk of innovations have more or less infinitesimal impact.

Because of diminishing marginal utility, economic growth can only be sustained by increasing the range and diversity of services provided to households. But increasing diversity intrinsically reduces the impact of each individual innovation.

To see this, consider the economy of the 18th century. 60% of the economy was agriculture, and 60% of that was grain growing. An innovation that improved grain growing productivity by 5% increased productivity of the whole economy by 1.8%. Fast forward to the 21st century. The largest single industry, healthcare, makes up maybe 10% of the economy, and healthcare in itself is very diverse (as are all large industries these days). An innovation that increases productivity in the whole of healthcare by 5% is unlikely to occur, and if one did eventuate, its global effect would be only 0.5%.

This can be compared to the increasing diversity and complexity of a forest ecosystem as pioneer plants take over bare land, and are succeeded by a bigger and bigger range of new species of organisms. At first total biomass increases, but over time it stabilises and new species increasingly compete with existing ones rather than complementing them.

The takeaway is that we should expect the benefits of innovation to decline as an economy grows. What we see is no surprise.

The dispersive discovery model imagines a random search through "innovation space". Potential innovations differ in impact size and in difficulty of production. Some innovations can only take place after others have been exploited - they are masked by the others.

The analogy here is the search for oil. Oil deposits vary in size, depth and cost of production. Drillers choose a location and a target depth, and drill down until they reach their target depth or they strike oil. They then exploit what they have found, if anything. Large, easily found and high-quality (low cost) deposits are rare - the distribution is log-normal at best.

Again, this perspective suggests that the returns to innovative effort should decline over time. Which is what we see.

Traditionally, arguments like these have been countered by pompous and vacuous assertions of the infinite demands and infinite resourcefulness of humans. To which I say, nihil sub solem infinita est. Strong assertions demand strong evidence, which has never been provided; and once you introduce infinities, you have left the realm of quantitative analysis and entered rhetoric.

Artir 2016-05-01T09:13:01Z

Some people who shared by post have said it was a 'debunking' of Gordon and Cowen. I don't say it is, and I don't think I imply it is. What I say here is consistent with what they say.

I agree with you in what you say in your comment. Ultimately, the laws of physics are the laws pf physics. We can get from converting energy from one type to another at better rates until we get >95%, and then not much else can be done. Things like stories, games, or cultural inventions may be potentially unlimited, but hard technology isn't. Even when considering that new capital goods can increase the productivity of older ones (e.g. roads and cars) because of their heterogeneity, there is a limit to this.

- Where has all the productivity gone? - Financial Times - Self Help Education Arena 2016-05-17T11:15:41Z

[…] Dietrich Vollrath explains how whole-economy productivity growth depends on which of these two possibilities is realized. Very roughly, when higher productivity in a sector draws more resources into it, this accelerates whole-economy productivity growth. When, in contrast, higher productivity in a sector means it makes do with fewer resources, which are released to lower or slower-productivity sectors, then whole-economy productivity growth is arithmetically pulled down. It seems very probable that the latter has been happening recently, since innovation and productivity within individual sectors have anything but fizzled out. […]

MRIN 2016-05-10T23:02:34Z

Ignore the economists is a choice I agree with! Even the ones I agree with.

Focusing on Peter Thiel's critique of innovation in the second half of the 20th century to present (type his name into youtube).

His basic question is: Outside of information technology what is there? I would appreciate your effort in understanding his perspective because it is considerably more nuanced and disturbing than you might at first imagine.

Stagnation can mean diminishing returns on improvements to existing technology. That you've addressed.

However you have not addressed the broader idea of stagnation in new innovations. New inventions. Cures for disease. Methods of exiting our gravity well. Even looser concepts like complex coordination of people. Methods of effective water filtration for closed loop household systems. Simple idea. Does not exist.

A decline in the rate of invention itself. This isn't easily examined by digging for statistics.

There is something intrinsically paradoxical about thinking of things that do not exist (or more likely: very nascent).

Tyler Cowen makes a point in a video with a reporter which speaks louder than all his analysis. His kitchen is effectively identical to a kitchen in 1950. Thiel has a good rule about technology. If it allows you to do more with less then it is a technology. Otherwise we are back to the world of trade offs and diminishing returns. That insight seems to have escaped a great many people.

The construction materials of houses have not materially changed in centuries. There exist new materials but it is a case of spending more money to get more stuff which only contributes to higher house prices. And lest we forget cures or broad spectrum drugs for universal ailments appear to have disappeared. This is suspicious. Oxford says there is exponentially declining effectiveness in drug search discovery. Let that sink in for a moment. I don't see that on many press releases.

If all modern technologies begin to fade into the background you will forgive anybody normal for coming around to the idea that the emperor has no clothes. Biotech has delivered not one large scale improvement for humanity. We might as well have never discovered DNA. I'm not making a joke here. There is surprising little evidence for utility from the Human Genome Project and its allies. Great for science but has had no meaningful effect on the population.

To wrap up. Thiel's ideas are not so easily dismissed. Where are the new weapons. New medicines. New materials.

Artir 2016-05-11T00:00:51Z

I admit I haven't dealt with stagnation in newer innovations. Indirectly, some of those will have found their way into my charts (e.g. transistors). Directly, the problem is that if something is the first of its kind we can't really construct a timeseries. We could see how many 'breakthroughs' have happened per year, and see if that figure is declining or not (I have a post on that half-sketched)

I'm not dismissing Thiel or Cowen, just saying one very narrow thing: we have timeseries for many techs, and these are getting better. I have not said anything about radical innovations, or as I explicitly mentioned, TFP, which is what matters for growth.

Anecdotically, I find plausible their arguments (the kitchen example), but anecdotically, I find opposite arguments plausible too. So I need to do research on that to have a proper opinion. I'll report back in this blog when I do that.

MRIN 2016-05-11T08:51:30Z

Look forward to hearing your (new!) thoughts. Take your time and I'll wander back here when you do.

As you can probably guess I'm from the school of thought that suggests having abundant data has the potential to mislead rather than clarify. In that sense we may be in a better place if we're forced to examine fundamental things carefully i.e. the first principals approach.

I must admit I find this entire discussion of this subject both fascinating and irksome. Fascinating because widely held beliefs about technological progress are in many specific areas built on pure air while the public believes it to have very solid footings. e.g. that we are in an era of stunning progress in developing new medicine.

http://lukemuehlhauser.com/wp-content/uploads/Scannell-Diagnosing-hte-decline-in-pharmaceutical-RD-efficiency.pdf

http://www.nature.com/nrd/journal/v11/n3/fig_tab/nrd3681_F1.html

The irksome part comes when people go: "lol, no, smartphones" as if that somehow negates a lack of material change in dozens of major industries outside of computation. Texas sharpshooter fallacy much? That's just painting the bullseyes around the bullet holes.

The fact is that computers have become so associated with technology is itself suspect because the word technology had a much broader meaning in the past. It takes a moment for people to associate things like faster travel or agricultural yields with technology. That 'pause' shows our present day bias.

In just three years time it will be a half century since we visited the moon. Half a century seems like an awful long time. It is also about that long since we had an implementation of a new nuclear reactor type.

I know there are 'canned' explanations for why we haven't been back but it is worth considering that the political explanations could be, you know, lies.

If you believe in tech stag as I do, then suddenly a lot of factors about rents, house prices, low interest rates and lack of wage increases suddenly click into place. Things like oil prices being at record lows but no dramatic effect on growth. Everywhere capital 'P' progress is declared by evangelical journalists, but I don't see it in people's lives in the west anymore. Even bright spots like ride/house sharing Airbnb/Uber or SpaceX seem like success stories buoyed up because they're floating in a sea of general failure. I'm happy about solar panels but that is very recent.

Of course this is anecdotal but the last word in the slogan for the Trump campaign is, interesting. It does not admit failure. It is like: "Well now, let us just move on". But from what? It is a clever way to admit to failure perhaps.

MRIN 2016-05-11T08:57:52Z

Ack, I lost a post. It had points interesting at least to me. In short:

Eroom's Law is real, no moon visits for half a century and having more data can sometimes obscure examination reality from first principals. I hope that makes sense. Notice the slogan of one of the contenders for president has 'again' at the end of it.

Anyway I look forward to your new post.

MRIN 2016-05-10T23:10:25Z

I will admit food became exponentially more delicious since the 70s.

- Links 5/13/16 | Mike the Mad Biologist 2016-05-13T20:44:34Z

[…] No Great Technological Stagnation The delusion continues No, ‘science’ didn’t ‘prove’ that dogs hate hugs The struggle with image glut: Experiments that generate millions of images have forced scientists to find new ways to store and share terabytes of experimental data The Pleistocene as Humanity’s Hyborian Age […]

Ray Van De Walker 2016-05-24T21:21:21Z

FYI, steam-based power production efficiency is stagnating because the steel used in boiler tubes has well-known temperature limits, and better materials are not economical, compared to simply making a larger power plant. The disruptive technology in stationary power plants is GE's H-frame combined-cycle natural-gas gas-turbines. They get a net thermal efficiency of 60%. They run a very large natural-gas-fueled gas turbine (qualitatively similar to a turboprop engine), and then use the heat from the exhaust to run a purpose-designed, bu trather conventional steam plant. The efficiency could approach 98% if the condensers of the steam plant could also sell hot water for district heating, but most places in the west lack the infrastructure to distribute it. Another cycle that was displaced by the H-frame turbines was coal power with a magnetohydrodynamic generator (essentially, a rocket engine that makes electricity) topping cycle: Efficiencies were similar, the technology was fully developed, but there was greater pollution (it's a coal plant) and slightly greater plant costs (MHD generators use exotic ceramics).

Blissex 2016-07-26T14:31:34Z

«steam-based power production efficiency is stagnating because the steel used in boiler tubes has well-known temperature limits, and better materials are not economical, compared to simply making a larger power plant»

This is interesting, but demonstrates one of the three points in my understanding of the "great productivity stagnation":

#1 The vast majority of productivity improvements in the past centuries is dues to the adoption of cheaper, more energy-dense fuels, in particular coal and oil.

#2 The productivity improvement resulting from adoption of a cheaper and more energy-dense fuel happens in two stages: the adoption itself, which at first is fairly inefficiently done, but still much better than the previous fuel, and a period of improvement in the use of the new fuel, of which things like higher temperature boilers and heat-recovery designs are example.

#3 No fuel has been found that is cheaper and more energy-dense than oil, and improvements in the use of coal tapered off a many decades ago, and of oil a few decades ago.

Engineering cleverness like materials for higher temperature boilers and hear-recovery designs are almost worthless without cheap energy-dense fuel.

Put in wider perspective, before "modern industry" the economy was based on farming, on consuming plant matter for energy, either as food for people or animal based muscle power, or wood for heat-based power. Therefore the economy was based on the fertility of farmland.

The discovery of concentrations of mineral wood (coal) and mineral oil has meant that those coal-fields and oil-fields are fantastically fertile farmland, delivering extremely cheap "food" and "wood" for powering "mechanical muscle" such as steam and oil based engines. The advantage a truck has over a mule is that its "food" is very much cheaper. Plus usually coal-fields and oil-fields happen to be in areas that are barren so they don't even compete for land with biological food-fields and wood-fields. The "oil farms" in the deserts of Arabia or Iraq or Persia are probably on the most fertile land ever discovered.

A very telling example:

www.economist.com/news/finance-and-economics/21699087-fad-andean-staple-has-not-hurt-pooryet-against-grain «They grow quinoa because little else thrives on their steep, barren plots. Their new competitors, tilling better soil with modern farming equipment, manage yields that are up to eight times higher. An ox takes six days to plough land a tractor can handle in two hours, explains Mr Livingstone-Wallace»

That two hours to six days is not because of the engineering cleverness of the engine in the tractor, but because the "food" to power the "mechanical ox" is vastly cheaper and more energy-dense than that to power a biological ox.

Carol 2016-12-29T15:29:04Z

It's simple. We're still washing clothes with soapy water instead of manipulating the dirt molecules in order them to behave as gas and just vape away from the clothes. The antigravitational and matterfield repeller haven't been invented yet, so flying cars are not possible, and dust repellers are not possible, and we still using the vacuum cleaner. We cannot disassemble and reassemble matter, so the teleportation is not possible, and it is also impossible to cure a disease by disassembling a sick body and reassemble its matter in a correct order. We can't read thoughts, so we can't record dreams, obtain police evidence by thoughts recording, or simply control any devices with the mind... We're definitely stagnated because there is no such a glimpse for that kind of technology. We're still living in the past.

- The Soviet Union: Productive Efficiency | Nintil 2016-11-07T21:49:59Z

[…] as R&D expenditures were increasing. Here I think he makes the mistake of equating TFP with technological progress, So to get the results he wants (🙂 ), he uses a CES production function rather than a […]

- Has Technology Stuck? | The Arts Mechanical 2016-10-23T04:06:33Z

[…] https://artir.wordpress.com/2016/04/25/no-great-technological-stagnation/ […]

bitcoin casino 2017-03-10T06:40:14Z

Howdy I am so delighted I found your web site, I really found you by error, while I was looking on Bing for something else, Anyways I am here now and would just like to say thanks for a remarkable post and a all round thrilling blog (I also love the theme/design), I don't have time to read it all at the minute but I have bookmarked it and also included your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back to read much more, Please do keep up the excellent job.

הפורומים בעברית 2017-10-17T12:05:03Z

Thanks designed for sharing such a pleasant thought, article is good, thats why i have read it completely

Citation

In academic work, please cite this essay as:

Ricón, José Luis, “No Great Technological Stagnation”, Nintil (2016-04-25), available at https://nintil.com/no-great-technological-stagnation/.

Comments