Kenneth Arrow on the welfare economics of medical care, a critical assessment

Kenneth Arrow wrote a paper in 1963, Uncertainty and the Welfare Economics of Medical Care. This paper tends to appear in debates regarding whether healthcare can be left to the market (like bread), or if it should feature heavy state involvement. Here I explain what the paper says, and to what extent it is true.

So lets see what the paper says.

Well, first of all, Arrow doesn't intent for the paper to be anything more than "an exploratory and tentative study of the specific differentia of medical care". If he says that, one wouldn't be surprised to find to find mistakes in the paper, as it is also quite a decades old. But on the other hand, Arrow won a Nobel Price, perhaps we was truly prescient and the whole thing has stood the rest of time.

He than claims that the "special features" of the industry essentially stem from the fact that healthare demand is strongly uncertain from an individual perspective, and that when markets fail, societies will, to some extent, come up with non-market social institutions to fix those market failures. But, he says, these institutions induce non-competitive practices in the healthcare sector, which prevents it from moving closer to optimality.

Special characteristics of the Medical-care market

Demand

(Unpredictability) First, unlike food or clothing, demand for healthcare is not as predictable. They are only purchased when one is ill, and illness is be hard to predict. That is, demand is driven by exogenous shocks, and not by one's own planning. Arrow finds it hard to think of goods and services for which the same thing holds. He can think of legal services (and he points out that there are some similarities with the healthcare sector).

(Criticality) Second, illness can cause death, permanent injuries, and loss of the ability to earn. Given that our life goals need us to be alive, and relatively healthy, it is of supreme importance to us to be healthy. The same holds for food, but food deprivation can be avoided if one has sufficient income.

Here Arrow is largely correct. The list of examples for the first special characteristic would be: healthcare, legal services, gadget repairing, home maintenance, or car maintenance. For the second characteristic, we can cite healthcare, food, water, and housing. Thus only healthcare meets both condition: It is the only possible critical good that has an unpredictable demand.

Or, to be precise, part of healthcare is. Like with some goods usually bunched in a single category, healthcare can be unbundled: cancer and heart diseases can be quite unpredictable and fatal, flu, headaches and cold can be mild and fairly predictable (usually around winter). There are few predictable and critical malaises, among them aging is probably the chief one. For highly unpredictable and low criticality, mosquito bites is one example.

Expected behaviour of the physician

(Moral provision) Healthcare is a service, not a physical good. Producing healthcare is synonymous with providing it, says Arrow. The customer cannot test the product before consuming it, and there is an element of trust in the relationship. This also holds for a barber. But the ethical standards required of the physician are higher. The physician must honestly take the patient's interests into consideration and act to further them instead of acting to pursue his own private gain. As an example of the special moral status of physicians, he mentions these special characteristics:

- Lack of advertising and overt price competition between physicians

- Advice given by physicians for further treatment is supposed to be divorced from self-interest

- It is claimed that treatment must be dictated by "objective needs" and not limited by financial considerations

- The physician is relied on as an expert in certifying the existence of illnesses truthfully, outweighing his desire to please his customers.

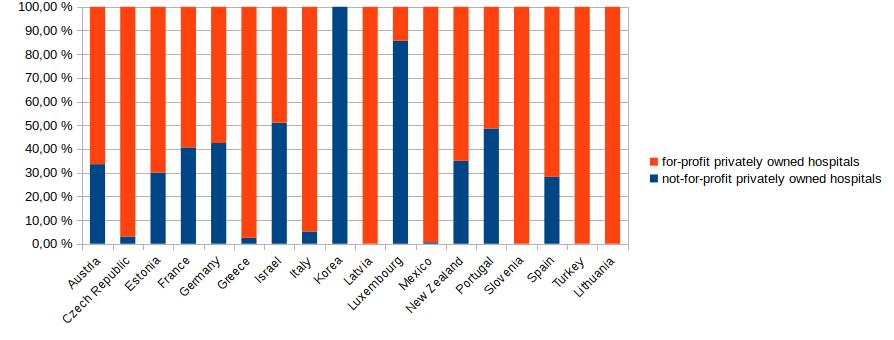

- Nonprofit hospitals predominate over for-profit hospitals (3 per cent in for profit, 30 per cent in voluntary non-profits. The remainder is in state owned hospitals). Arrow posits two possible explanations

Two of this items are at least quite false, the others are argueable. Starting from the bottom, he might have been true about the US in 1963. But he didn't look further beyond (Perhaps the information wasn't available then). Had he done so, he would have found this (from OECD data, 2015)

For the countries that we have data for, most private hospitals are for-profit, except Korea, Luxemburg, and the US. And even in the US, while there were 10x more non-profit hospitals back in 1963 as Arrow says, but 1975 there were only 4.3x more. By 2013, only 2.7x more.

Next, lack of advertisement and overt price competition between physicians. This also has to be unpacked. We don't see either advertisements from particular individuals for commercial purposes. Smaller entities usually rely on word of mouth and small scale networks to gain reputation and customers. This holds for bakeries and small medical practices. For larger entities, advertising does make more sense. We can find advertising for health insurance (here or here). We can even find advertising for hospitals (here, here, here, here) I will grant that there is't much advertisement for hospitals, it is true. This may be because people don't care much for a particular brand (like, in many cases, with supermarkets). The services you can get at one, you can get at all of them, and many people will go to the nearest one. The rare exceptions would be elite hospitals in one's own city or country where they may have state of the art facilities and highly skilled specialists. These hospitals would also fall under the local network advertisement effects. In a given city, there may be two or three of these, and given that hospitals tend to stay in the same place for a long time (decades), they will get to become well known. This is to some extent like hotels. Hotels don't advertise that much for the same reasons.

Next, price competition is indeed an issue in the US. It is difficult to find prices for treatments online in the US. In the UK it doesn'tseem that difficult. It is more difficult for Spain. My overall assessment is that indeed there is little price competition -as Arrow says. Why the situation in the UK is like that and not in the US? This deserves further investigation, but again shows that lack of price competition is not an intrinsic characteristic of this market.

Next we have the extra bundle of ethical obligations that physicians are said to have. But in this regard, they are not prima facie dissimilar from a butcher counseling you on what the best cuts of meats are for a given purpose, or a data science consultant (like me!) you hire to help you improve your business, or a car mechanic, or even a CEO. In those cases, you know less than the professional about what you really need, so some intrinsic moral motivation is needed for a fully fruitful and honest transaction -at least in the short term. In the long term, reputational effects may kick in-. So this is not a special feature of the moralisation of healthcare, but of the fact that doctors as professionals know more than you do. Fortunately, not only in these cases but in most, people want to be good at doing their jobs. Having a self-image of "a good doctor" can be very important for one. (See section 2 here for example).

Product uncertainty

(Asymmetric information) With many commodities, you can learn from your or other's experience about the nature of the good purchased. With illness, it is more difficult. You sort of know what a good mango is, and how pricey it should be. If not, you can easily find a mango-eating friend. But it is far harder to do for cancer, or hip surgery. You don't know beforehand what you will be getting. The physician is aware of this, and knows more than the patient. Arrow says this is uncommon.

While in general it is true, it is not true for the services mentioned in the previous section. You don't know what is needed to repair a car beyond broad details, for example.... unless you want to. What does a hip replacement surgery involve? No idea, but then I can google "hip surgery" on google and get an idea of what it takes. You can see that it will involve surgery with anesthesia, that it will cost between 8 and 16 k£, that it involves removing the damaged hip joint and replaced with a metallic or ceramic artificial joint. You can also see the side effects, and expected recovery time. This greatly closes the gap in knowledge. Perhaps this information wasn't easily available in 1963, but now it is.

Supply conditions

(Licensing) The supply of is commodity is tied to the expected return from its production. For healthcare some elements insert a wedge between returns and supply. One is licensing, which restricts supply. This policy tends to be justified by the desire to provide a minimal level of quality. I personally doubt that to get decent healthcare (or services in many other regulated professions) the current standards are needed, but that's another matter. In the US, education of physicians is also tightly regulated, resulting in expensive education, and adding to the limitations on the supply of physicians.

Pricing practices

(Price discrimination) The sector practices it. Hospitals charge the rich more and the poor less (even nothing for the truly poor). There is also opposition to pre-payment from the side of hospitals, and to closed-panel practice (binding the patient to a particular group of physicians). Arrow provides no evidence for this, altough the first part seems plausible enough to accept it without further investigation. The second part is hard to understand, as one common insurance offering is precisely to tie the user to hospitals or medical experts tied to the insurance groups.

Comparison with the competitive model under certainty

Nonmarketable commodities

(Negative externalities) The case of vaccination as fixing a negative externality.

(Other-regarding preferences) People care for other people's health. People usually don't care about what other people do, so this is another difference.

Well, yes.

(Increasing returns) Hospitals show them. Equipment and specialists are indivisible, so it makes sense to aggregate them in units (hospitals) that work better than if the components were separate. This can decrease competition.

But, as he admits, transportation and concentration in cities ameliorates this issue. In addition, the prevalence of small clinical practices in many parts of the world suggest that returns are not that increasing in general. They may be for certain surgeries, or certain high-end equipment.

(Licensing and educational costs) Discussed above

Arrow says that if the requirements were relaxed, the output would be of lower quality. This need not be so if education acts to some extent a signaling rather than as human capital buildup, or if there are faster ways of training doctors than currently practiced, or if some procedures can be left to less trained specialists (Who will perform them equally well).

(Price discrimination) Price discrimination, says Arrow, is inconsistent with the competitive model. Here I wonder to what extent price discrimination exists in reality. I imagine that it will be more prevalent there were hospitals do not publish their prices, as if they did it would be difficult afterwards to charge more to some. There is also some rationale for that practice if hospitals seek to subsidise the poor at the expense of the rich. I am thus willing to concede that Arrow is right for the US.

(Moral hazard) Being insured reduces one's incentives to avoid illness, and on the other hand insurance companies will try to pay as little claims as possible.

(Predictability and insurance) The more unpredictable an illness is, the more risk averse individuals will be willing to pay to insure against it.

(Pooling of unequal risks) In theory, insurance companies would charge more people who are less healthy, but there appears to be a tendency to equalise costs, which would not exist if markets were competitive, says Arrow.

(Gaps in coverage) Not everyone is insured.

Conclusion

What then, makes healthcare special? Summarising the above, and dividing healthcare into its components, plus adding some of examples that share similar "weird" features:

| Externality | Uncertainty | Life Critical | Price | Information assymmetry | Moralisation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communicable diseases (vaccines) | Yes | High | Some | Low | Medium |

| Major medical treatments (cancer, heart surgery) | No | Very high | Yes | Very high | High |

| Minor medical expenses (painkillers, cold medicine, medical checkups) | No | High | Not usually | Low | Low |

| Car breakdown / Legal services | No | Very high | No | Medium | High |

| Food | No | None | Yes | Low | Low |

| Consulting services | No | Medium | No | High | High |

Most of the debate around healthcare tends to focus on a piece of it: major medical treatments (and secondly on drug prices). One rarely knows when one will need them, they are very expensive, and you don't know exactly what the treatment will involve (initially). Because most people cannot afford them, insurance is typically needed. Insurance need not (but can) be expensive. In the US, monthly premia can range from 150 to 470$ in the individual insurance market, while in Spain, you can get the best insurance available in the marketfor around 115€, and a cheap one for 50€.

Those treatments are also moralised in the minds of many people: they _have to _be available to everyone, without regards for the cost (!). Some people think some features of this market are proof that the market for healthcare doesn't work. One example is pre-existing condition coverage. Someone with cancer who purchases a new policy (even if he manages to!), won't be covered for expenses due to cancer. But this is a feature, not a bug: The premium is really the expected cost to you plus a markup. If the cost is known with certainty, then the premium equals the total amount. Trying to "fix" this feature of the market by doing things like mandating that everyone pays the same, or that insurer cover everyone undermines the workings of the market. If one really wishes to cover those people, it would be far better to redistribute towards them.

The second aspect of the paper is to explain how these peculiarities incentivise the creation of institutions to overcome them. Insurance is what happens when you have budget contrained, risk averse people, and highly uncertain pricey treatments.

Other features of this market are not as clear cut as Arrow explains in his paper (the uniqueness of medical ethics, or the status of hospitals as non-profits, or medical licensing).

What special features, I add, would we really expect to see to overcome the peculiarities? Transparent pricing at hospitals, websites to do healthcare-shopping easier, and lifelong all-risk health insurance. As I've shown in with a few examples, these features are not similar everywhere. The US ranks very low on transparency, while the UK ranks high. It is easy to get affordable cover for life in Spain (covering even non-preexisting chronic conditions like diabetes), but not so in the UK, except for cancer. Why are these markets different? I don't know, but it is a topic worth looking into.

These points and many others have been already addressed in this article, which I didn't initially notice. This other article deals with the relevance of asymmetric information in modern times. Here's John Cochrane reply to Noah Smith.

I am currently reading through Jonathan Gruber's Public Finance, where a modern treatment of this topic is presented. I haven't gotten to the health insurance section, so for now I can say that reading Arrow's paper fails to convince me that healthcare cannot be mostly left to the market. I don't expect that this post will win you over to my side of the question. For that I would need something focused specifically on that, not just a critical assessment of an old interesting paper. I should probably also have a look at chapters 20-25 of the Handbook of Health Economics.

A fuller assessment of the question would involve a presentation of the most up to date theoretical treatment of the issue, empirical evidence on how modern day healthcare markets work around the world (beyond the US or Europe even), and historical evidence about how healthcare markets became what they are now.

Finally, I want to mention that some people grossly misunderstand what Arrow says in his paper. There he is not arguing or defending a single payer system. He is not even saying that "the laissez-faire solution for medicine is intolerable" as some people have said. That last line he does say, but referring to medical licensing, and that is not something he believes, but something that he says is the general social consensus.

If you have sources that deal with this market that I should read, please do tell me in the comments. The landscape of the debate seems one where there is consensus among economists that a free market in healthcare is too troublesome, yet then there are people who easily poke holes in those arguments and then they go unanswered. I stick to my principle that one should defer to a scientific consensus where it exists unless there are reasons to doubt it, and this case seems like one of those exceptions.

Edit 2021-03-15

A reader sent me some critical comments that I reproduce below. This is acknowledged in the Mistakes page. Below is a response to those comments.

Critique of my post

So I was linked your blog posts on healthcare recently, and found that I could be paid to criticize it, so here's my attempt:

Firstly, your post on Ken Arrow’s paper. I believe that pretty much all of the disagreement with Arrow in that section is incorrect.

In Section 1.2 of that post, you make the claim that because hospital advertisements exist, Arrow must be incorrect. I disagree with this because I do not think advertisements for healthcare services have nearly as large of an effect you assume they must have. When I looked into how customers choose the hospitals they go to, I found that distance and physician referrals were the two biggest factors. A German study looking at hospital selection found that it was physician referrals that had the greatest influence in a patient's choice, and pricing/advertisement wasn't even in the list of factors. This is consistent with evidence from the US.

Next, you make the claim that it is difficult to shop around in the US because it’s difficult to look up prices, and therefore, it is not an intrinsic characteristic of the market. I believe this is incorrect as well, because I’ve found plenty of evidence that price transparency doesn’t help and that physician referrals play the largest role in determining where a patient goes (see hospital studies above). It seems intuitive that ensuring that all prices are available would make it easier to shop, so more people would do so. After all, people can't shop around if they can't even see the prices to begin with! Unfortunately, transparent pricing doesn't seem to help either, largely because most people simply don't use them. This isn't because of any lack of encouragement or enthusiasm either. This study surveyed 2,996 non-elderly Americans and found that despite the vast majority strongly agreeing that shopping around is a great idea, only 13% of them actually sought out price info while only 3% actually compared prices before receiving care. For further reading, I suggest you look into these: [1] & [2].

These results aren't unique to the US either. A study on the effects of transparent pricing in Singapore found that there is no evidence of any marked decrease in prices in the years following the implementation of price transparency legislation. Even more interesting is that this research paper found that healthcare costs in Singapore actually increased when the government loosened regulations, because hospitals bought expensive new technology and focused on premium care while neglecting the lower levels for poorer citizens. This led to the government once again tightening its hold.

Lastly, a study that looks at the rates at which people shop around for MRIs found that people typically get their M.R.I.s wherever their doctors advise. In fact, on the way to their M.R.I., patients drove by an average of six other places where the procedure could have been done more cheaply. Read this article for a more in-depth explanation of the study. This means the lack of price shopping isn’t exclusive to major services.

I think the fact that people don’t shop around is an intrinsic market failure, unlike your claim in the post.

The problem with Section 1.3 draws on the same preconceived notion that people don’t shop because it is difficult to find prices and info. This actually isn’t the case. As I stated previously, people rarely seek out price info and the same applies to information. While information may be easy to find, people rarely use it.

Next, there are issues with the healthcare section of your post on the non-non-Libertarian FAQ as well.

In Section 8.2, you refute Scott’s statistics from BCBS. I guess I can’t fault you for that, but I disagree with the notion that government healthcare is not more efficient. I think that Scott used a bad example. I would like to provide a counterexample from the CMS. Look at the CMS data on National Health Expenditures here (The link gives you a security warning for some reason, but it's safe since it's a pdf download on data from the government). The sum of federal government spending on health care is greater than private insurance spending (1.2 Trillion vs. 1.1 Trillion), yet the government's administrative costs are $42 billion, vs private net cost of insurance of $210 billion. That’s a really strong argument the government can be more efficient. Its a direct saving of $160 billion, and many argue that the government is still inefficient and costs can be even lower.

In addition, a mercatus center study (A Libertarian biased think tank btw) finds that we would save on admin costs by switching to single payer. The data is on page 7. Overall NHE is shown to decrease under single payer.

In Section 8.5, I think the evidence on for-profits and nonprofits are a lot more mixed than you make it seem. because research shows that public hospitals are as efficient as private, if not more or it's inconclusive results that sorta lean towards public being better. Private hospitals are also known to respond more to financial incentives, which can turn out to be a bad thing.

Then you bring up Singapore as an example of how the market can work and that its system can be replicated with the market mechanism. I don’t see how you can maintain a free market while replicating policy like the heavy price controls in Singapore. To address Brian Caplan’s points, he argues that Singapore's system works because of the extensive cost sharing. While it is true that cost sharing reduces total healthcare expenditure, a study looking at evidence from HDHPs cost-sharing does not seem to decrease prices. This conclusion is supported by further evidence. Caplan then argues that there is a lot of comparison shopping in healthcare in Singapore, but there doesn;t seem to be much evidence of this either. As I stated above, a study on the effects of transparent pricing in Singapore found that there is no evidence of any marked decrease in prices in the years following the implementation of price transparency legislation. The hospitals customers choose to go to likely depend on distance and physician referrals, like with most other developing nations. I think you should take a look at this article and this. The singaporean system is most likely not reproducible.

Regarding India, you make a point that private hospitals are delivering world-class care at a tenth of the cost, but I have my doubts regarding how reproducible it is in developed nations. Wages, costs of living, drugs, etc are all far lower in India, so I don’t see how it is a good comparison to the US.

Anyways, that’s about it for my criticisms. A lot of the content for this came from the healthcare post I wrote on reddit so that I may have everything in one place. I think you should take a look at it when you have the time!

My response

I will reply to all the comments, but take into account that the Non-Non Libertarian FAQ was written prior to 1st of Jan of 2017, the policy in my blog set that as a cutoff date (Which I haven't changed since then) for payments.

Section 1.2, advertisements, etc. You give some evidence for patient choice for hospitals. Yet in that section I cite various forms of health-related ads (Insurance besides hospitals) while granting that there isn't much advertisements for hospitals, and This may be because people don't care much for a particular brand . In fact, that whole paragraph's point is to explain why don't we see many hospital ads, and why people probably don't care much about the hospital. Lastly, that paragraph doesn't say anything abut the effectiveness of said ads. Arrow is saying "there are no ads", I am saying "Yes, to some extent there are".

Price competition, etc. I do make the mistake, it seems, to infer that "prices available imply price competition". Regardless of empirical evidence that claim I make doesn't seem to me as solid, so that's a mistake. Now, on price availability I don't think your evidence is that good. The problem with this is that choice is relative to costs and benefits of making said choice. For example, if price information is not useful or hard to find, that "price transparency" will do very little. Similarly if patients believe that most hospitals are the same then they won't discriminate between them.

Specifics bits of evidence

* Desai et al. on a "cost reduction tool", the paper itself points to conflicting findings in the intro from other work due to the tools used and patient populations studied. Many providers in this study lacked quality info (Suppose there is a place near you that has good reviews but is 10% more expensive and another place that is cheaper but knows nothing about. This alone may explain a decision). Lastly, people do search and they search more the more the tool has been available. Perhaps it takes time for people to think of the tool next time they are thinking of these shoppable procedures. The authors mention some of this in policy implications and note that it did decrease average price paid for imaging.

* Mehrotra et al. seem to corroborate my point if anything. On my view, if you make it easy for people to price shop, they will price shop, and that should exert some pressure on prices. This alone is not the only reason why healthcare is expensive. But on this count I would be wrong if people, when offered sufficient information they can act on (and benefit substantially from) don't do so. The paper notes one caveat that seems substantial, and is that if patients pay the same regardless of where they go (They have a good enough place that's in network) they may not price shop. I'd add that if someone is signed up to an HMO (As, as it happens, I am, with Kaiser) one is not going to priceshop either. One has done so previously when one picked a healthcare plan. The paper notes "75 percent of respondents said that they did not know of a resource that would allow them to compare costs among providers (data not shown)" and "Not surprisingly, respondents were most likely to have sought cost information for higher-cost services such as outpatient procedures.". It makes sense to spend little time looking for pricing info if you know there's little of it. Plus the one you can find can be very obscure to interpret (Have you seen this? Can anyone make sense of that for their own case?) Lastly the paper points, and I think this is the biggest thing "Price information must be more accessible and comprehensible to patients."

* Sinaika et al. is like the Castlight study but it seems more comprehensive than what people were searching for in Castlight(Not just labwork and imaging, but colonoscopies, surgery etc). It also shows that pattern where usage of the tools increases greatly as time goes by. Also: "Our finding that people with greater out-of-pocket expenses were more likely to search the Member Payment Estimator likely reflects the fact that consumers with generous insurance are insulated from price variation and are less sensitive to price" and "Whaley and coauthors found that searching for price information was associated with lower payments for advanced imaging and laboratory tests, compared to payments for these services for nonsearchers." (So sometimes one does see effects in cost)

One comment on doctors and people doing what they say, yes that's real. And it is reasonable. But why do doctors tell patients to go to more expensive places? What are the incentives in place that keep costs high? Do these doctors know that there are indeed cheaper places? From one of the studies "Going forward, our work suggests that health care funders could more effectively steer patients towards high productivity providers by equipping physicians with information on the prices of potential locations for care and incentivizing them to make more cost-efficient referrals. These results are consistent with Ho and Pakes (2014), which find that insurers with more direct control over physician referrals are able to get lower priced secondary care and research on payment reform that suggests that when physicians are incented to make referrals to lower priced locations, they do so (Song et al. 2014; Carroll et al. 2018)"

Moreover, this year the US is getting "price transparency". Will that do much? I expect it will not, for the reasons here . To wrap up, "real price transparency has never been tried" in general, so the evidence her does not warrant me thinking that lack of it is an intrinsic part of this market, or that the presence of it will not induce price competition. What would falsify this? Say Amazon opens a new hospital chain and have the exact prices you'll pay for anything in their website, so you can see exactly how much money will leave your bank account. Assume those prices are cheaper than other hospitals around. If people do not flock en masse to that hospital I will be wrong. To wrap up, I think this from Frakt and Mehrotra is close to what I think: Yes, price transparency has been disappointing so far but it doesn't mean it should not be part of a broader strategy. To make a similar with healthcare, curing cancer won't improve life expectancy by much (Because you still get CVD). Likewise for CVD (You still get cancer). Cure both and you get substantial benefits. With a healthcare system, piecemeal changes may seem ineffective when tried individually.

Hence, I continue to maintain that lack of price competition is not an intrinsic characteristic of a healthcare market in theory, even if we indeed don't see a lot of competition right now.

The Non-Non Libertarian FAQ

Section 8.2: I don't say that government healthcare is not more efficient. It can be more efficient. In fact, for example the NHS is more efficient than the US private healthcare side of things. I just say that that particular example does not show such a thing. To assess administrative efficiency one has to account both for how many people are enrolled, how sick they are and how much care they get. For example, basically everyone in Medicare is over 65, which means that they probably spend more per person. That would inflate the spend even when it costs the same to administer the program, making the share of admin costs lower.

Moving towards single payer does not, by itself, reduce prices. This is the same problem as with price transparency. Suppose you nationalize the entire US healthcare system overnight. Now it's publicly owned, but it costs the same. Now you could reduce doctor's salaries, you could streamline admin costs, you could ban hospitals from MRIng everyone, etc. Then it would cost less. Ownership by itself does not change anything, one needs to consider the entire set of changes.

As it happens, that Mercatus article makes the same I just thought of (And the savings implied in their model are, according to them, a generous estimate in favor of single payer):

"Current administrative cost rates for Medicare as a whole are cited as being roughly 4 percent, though closer to 6 percent for Medicare Advantage.38 It is unlikely that the population now privately insured could be covered by M4A with administrative costs as low as 4 percent. Administrative cost rates are calculated as a percentage of total insurance costs, and these total costs per capita under private insurance are currently less than half of what they are in Medicare.39 In other words, one reason Medicare’s administrative cost rates appear to be so much lower than private insurance rates is that they are expressed as percentages of Medicare’s overall per capita costs, which are much higher. These higher Medicare costs exist primarily because Medicare serves an older population that consumes more healthcare services than the generally younger population now served by private insurance"

Section 8.5, hospitals and for-profits I agree. That's a mistake I made. The latest review I could see https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0093456 does point to conclusions being mixed other than for-profit hospitals being worse than non-profit hospitals (Which I do acknowledge in the original post). In my defense I can only add that I did write that "results don't seem robust" and it's a particular point I did not spend much time reading about when I wrote the FAQ.

Singapore

I do not say this is an example of how the market can work, I say that there is plenty of government intervention. Now is when I can take out the systems-level card again (Can't evaluate single interventions without taking into account the rest of the system), but this seems kind of lazy on my side; as lazy as the Singapore paragraph in the original FAQ I wrote. I should have wrapped that paragraph in "speculative" because I didn't look much into that last section.

India

Those points you make are reasonable. But I do not make the general claim that all Indian hospitals are good in general, I argued that some are. The specific hospitals that I point to as being Western-level are the ones I mention in those articles. It seems some of the articles in the FAQ don't work anymore. In any case obviously those things you mention should be accounted for and I took them into consideration when linking that. In the HBR piece they note that Even with the higher wages factored in, the cost was still only 4% to 18% of a comparable procedure in a U.S. hospital. Material costs are not necessarily cheaper (Also pointed out in the article). The point of that case study is breaking down where savings are coming from: "They achieve this cost reduction by productivity increases: At NH, each surgeon performs from 400 to 600 procedures a year, compared with 100 to 200 by U.S. surgeons. Similarly, Aravind doctors each perform from 1,000 to 1,400 eye surgeries a year, compared with an average of 400 by doctors in the United States." etc. Can whatever is it that they do be replicated in the US? Not everywhere (You need some volume to max out doctor utilization), but in big cities, why not?

--------

So given this, I propose the following, if you agree. I will append your email to the bottom of my Arrow article, along with my reply. I will then link to the Arrow article from the FAQ so that your reply is visible from there as well. (I will edit the email keeping just the content, but preserving a link to your healthcare post).

I remain unconvinced that market-based healthcare will be inferior to something like the NHS or a German model. I also think that the only way to cleanly look at this issue is with systemic trials where multiple policy changes are done at once (perhaps in a given region), with a commitment to stability for years, and then seeing what that did. I hope I don't seem unreasonable given the broader context; as you can see in my blog I write about many different topics and I could probably spend a year reading just about healthcare (Instead, maybe it's more useful to read about how to cure aging hah).

Now, there's the question of how wrong I am in the Arrow piece. On one hand I could say that given that I have not changed my mind I have made no mistakes, but you a) Made me realise I did make a mistake in inferring prices->competition (Which is independent of the empirical evidence) and b) Pointed out my mistake with non-profit vs for profit hospitals in the NNL FAQ which was still useful, and c) Pointed out my lazy assessment of Singapore and perhaps also d) You just made the effort to review my writing .

Comments from WordPress

-

Los sistemas sanitarios: algunos enlaces. | PHILONOMICS 2017-07-12T22:38:37Z

[…] Kenneth Arrow on the welfare economics of medical care, a critical assesement […]

-

Rational Feed – deluks917 2017-07-13T01:55:51Z

[…] Kenneth Arrow On The Welfare Economics Of Medical Care A Critical Assessment by Artir (Nintil) – “Kenneth Arrow wrote a paper in 1963, Uncertainty and the Welfare Economics of Medical Care. This paper tends to appear in debates regarding whether healthcare can be left to the market (like bread), or if it should feature heavy state involvement. Here I explain what the paper says, and to what extent it is true.” […]